Chapter 1 Prelude to a TurbulentAge

Canthere be a connection between online universities and the serial insurgencieswhich, in media noise and human blood, have rocked the Arab Middle East? Icontend that there is. And the list of unlikely connections can easily beexpanded. It includes the ever faster churning of companies in and out of theS&P 500, the death of news and the newspaper, the failure of established politicalparties, the imperial advance across the globe by Facebook and Google, and thenear-universal spread of the mobile phone.

Shouldanyone care about this tangle of bizarre connections? Only if you care how youare governed: the story I am about to tell concerns above all a crisis of thatmonstrous messianic machine, the modern government. And only if you care aboutdemocracy: because a crisis of government in liberal democracies like theUnited States cant help but implicate the system.

Alreadyyou hear voices prophesying doomsday with a certain joy.

Iam no prophet, myself. Among the claims I make in this book is that the futureis, and must be, opaque, even to the cleverest observer. Consider CIAand the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, or the Fed and the implosion ofLehman Brothers in 2008. The moment tomorrow no longer resembles yesterday,we are startled and confused. The compass cracks, by which we navigateexistence. We are lost at sea.

Butwe can speak of the present. And I think it demonstrable that an old,entrenched social order is passing away even as I write these words onerooted in the hierarchies and conventions of industrial life. Since nosubstitute has appeared on the horizon, we should, as tourists flying into the unknown,fasten our seatbelts and expect turbulence ahead.

Information Is Cool,

So Why Did It Explode?

Icame to the subject in a roundabout way. I was interested in information. Theword, admittedly, is vague, the concept elusive. Information theory findsinformation in anomaly, deviation, difference anything that separatessignal from noise. But thats not what I cared about.

Mediaprovided my point of reference. As an analyst of global events, my sourcematerial came from parsing the worlds newspapers and television reports. Thatwas what I considered information. I also held the belief that information ofthe sort found in newspapers and television reports was identical to knowledge so the more information, the better. This was nave of me, but if I say so,understandable. Back when the world and I were young, information was scarce,hence valuable. Anyone who could cast a beam of light on, say, Russia-Cubarelations, was worth his weight in gold. In this context, it made sense tocrave for more.

Acurious thing happens to sources of information under conditions of scarcity. They become authoritative. A century ago, a scholar wishing to studythe topics under public discussion in the US would find most of them in thepages of the New York Times. It wasnt quite All the news thats fitto print, but it delivered a large enough proportion of published topics that,as a practical proposition, little incentive existed to look further. Becauseit held a near monopoly on current information, the New York Timesseemed authoritative.

Fourdecades ago, Walter Cronkite concluded his broadcasts of the CBS NightlyNews with the words, And thats the way it was. Few of his viewers foundit extraordinary that the clash and turmoil of billions of human lives,dwelling in thousands of cities and organized into dozens of nations, could becaptured in three or four mostly visual reports lasting a total of less than 30minutes. They had no access to what was missing the other two networksreported the same news, only less majestically. Cronkite was voted the mosttrusted man in America, I suspect because he looked and sounded like thewealthy uncle to whom children in the family are forced to listen forprofitable life lessons. When he wavered on the Vietnam War, shock wavesrattled the marble palaces of Washington. Cronkite emanated authority.

Ittook time to break out of my education and training, but eventually the thoughtdawned on me that information wasnt just raw material to exploit for analysis,but had a life and power of its own. Information had effects. And the firstsignificant effect I perceived related to the sources: as the amount ofinformation available to the public increased, the authoritativeness of any onesource decreased.

Theidea of an information explosion or overload goes back to the 1960s, which seemspoignant in retrospect. These concerns expressed a new anxiety about theadvance of progress, and placed in doubt the nave faith, which I originallyshared, that data and knowledge were identical. Even then, the problem wasframed by uneasy elites: as ever more published reports escaped the control ofauthoritative sources, how could we tell truth from error? Or, in a moresinister vein, honest research from manipulation?

Informationtruly began exploding in the 1990s, initially because of television rather thanthe internet. Landline TV, restricted for years to one or two channels in afew developed countries, became a symbol of civilization and was dutifullypropagated by governments and corporations around the world. Then came cableand the far more invasive satellite TV: CNN (founded 1980) and Al Jazeera(1996) broadcast news 24 hours a day. A resident of Cairo, who in the 1980s couldonly stare dully at one of two state-owned channels showing all Mubarak all thetime, by the 2000s had access to more than 400 national and internationalstations. American movies, portraying the Hollywood approach to sex, pouredinto the homes of puritanical countries like Saudi Arabia.

Commercialapplications for email were developed in the late 1980s. The first server onthe worldwide web was switched on during Christmas of 1990. The MP3 destroyer of the music industry arrived in 1993. Blogs appeared in 1997, andBlogger, the first free blogging software, became available in 1999. Wikipediabegan its remarkable evolution in 2001. The social network Friendster waslaunched in 2002, with MySpace and LinkedIn following in 2003, and thatthumping T. rex of social nets, Facebook, coming along in 2004. By2003, when Apple introduced iTunes, there were more than 3 billion pages on theweb.

Earlyin the new millennium it became apparent to anyone with eyes to see that we hadentered an informational order unprecedented in the experience of the humanrace.

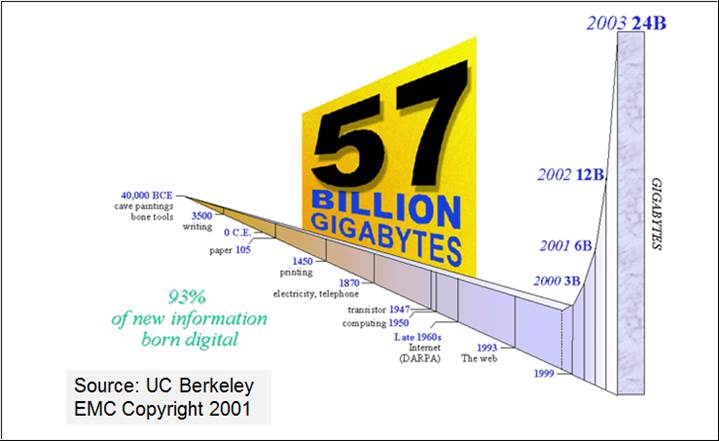

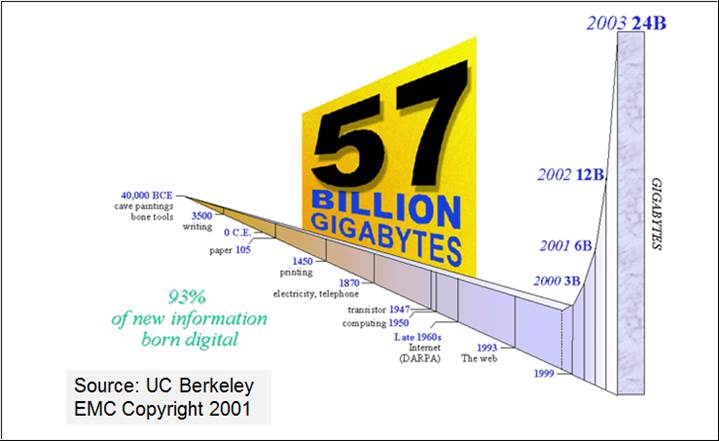

Ican quantify that last statement. Several of us analysts of events weretransfixed by the enormity of the new information landscape, and wonderedwhether anyone had thought to measure it. My friend and colleague, Tony Olcott,came upon (on the web, of course) a study conducted by some very cleverresearchers at the University of California, Berkeley. In brief, these cleverpeople sought to measure in data bits the amount of information produced in2001 and 2002, and compare the result with the information accumulated fromearlier times.

Theirfindings were astonishing. More information was generated in 2001 than in allthe previous existence of our species on earth. In fact, 2001 doubledthe previous total. And 2002 doubled the amount present in 2001, adding around23 exabytes of new information roughly the equivalent of 140,000 Library ofCongress collections. Growth in information had been historically slow and additive. It was nowexponential.

. V olume of information is doubling every year

. V olume of information is doubling every year

. V olume of information is doubling every year

. V olume of information is doubling every year