All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Introduction

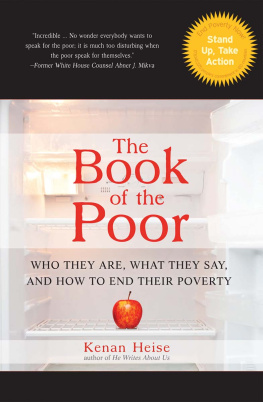

In her letter dated 1st July the heroine of this short novel uses a Russian phrase which is ultimately untranslatable, the insurmountable difficulty lying in the two alternative meanings of the word dobro , both of which make sense in the context. The phrase either means to do good or to create wealth. As well as setting a frustrating puzzle for the translator, this ambiguity which is suggestively combined with the word selo , village, in the heroines surname too encapsulates the mixture of social and moral themes in Dostoevskys first published work in much the same way as does the title. For thankfully just as in English too this time the Russian adjective bedny , poor, can imply both material poverty and spiritual, moral impoverishment, either of which conditions might provoke pity.

The most obvious level on which the novel operates is probably that of the crusading social manifesto. Dostoevsky depicts protagonists who exist in penury in the hard heart of a nineteenth-century metropolis. The reader cannot help but be moved by the plight of Varvara Dobroselova and Makar Devushkin, authors of the letters that form the bulk of the text, as well as of the other figures, such as Gorshkov and Pokrovsky, whose stories echo to one degree or another those of the central characters. Certainly this was the main reason for the critical acclaim the work initially attracted. But the author equally shows that material comfort is not all a human being needs to achieve spiritual peace. One of the ironies of the closing pages is that just as things seems to be improving materially for a number of the characters, so the spiritual fabric of their lives comes apart. The welfare state can provide people with a decent income, accommodation, an education, but not with the less tangible factors that arguably contribute still more to contentment such as requited love, the respect of other men, or a sense of personal dignity. What does honour matter, asks the hack novelist Ratazyayev, when youve nothing to eat? The great novelist Dostoevsky would without doubt reply: It matters a great deal.

Yet as well as functioning on these social and spiritual planes, Poor People is a work much concerned with things literary. Indeed, a proper understanding of Dostoevskys purpose is impossible without some knowledge of the literary context, for the work is highly allusive in its content. The title itself is a clear reference to the best-known story by Nikolai Karamzin, belletrist and historian, the man lauded by Alexander Pushkin in 1822 as Russias finest writer of prose. Poor Liza, published in 1792, was his best-selling sentimental tale of the seduction and abandonment by a well-connected young man of an innocent peasant girl. The sad story ends with her suicide and the tears of the compassionate reader. Pushkins praise for Karamzin was modified by his recognition of the dearth of competition in prose fiction, but by the 1830s the great poet had dethroned his predecessor by producing outstanding short stories of his own. In The Queen of Spades Pushkin created his own poor Liza, an orphaned ward who is jilted without even being seduced, yet finally makes a profitable marriage. Before this, however, Pushkin had already published The Tales of Belkin , a collection which in Poor People is sent by Varvara to Devushkin, arousing his great enthusiasm for the story The Postmaster. What Devushkin does not realize as he praises the authenticity of Pushkins portrait of one of lifes humiliated and insulted, is that Pushkin was here giving an ironic rereading of Karamzin. Pushkin has poor Dunya, the daughter of the eponymous station master, quite willingly seduced by a wealthy young man, but this time there is no abandonment; rather it is Dunyas father, assuming she will come to a bad end, who turns to drink and dies. Devushkins delight at the story is prompted by his recognition of himself in the figure of the postmaster and by the sympathy the latter elicits from the narrator. But being an unsophisticated reader, Devushkin does not appreciate all the parallels between the situations of Dunya and his own protge, Varvara, and he certainly does not understand the irony in Pushkins depiction of tragic delusion.

The other work that has a profound effect on Devushkin is Gogols short story The Greatcoat. Here too he recognizes a portrait of himself in the figure of the impecunious copying clerk who is obliged at the cost of great hardship to buy a new coat to keep out the winter cold of St Petersburg. Unfortunately this adored new possession is immediately stolen, the clerks feeble plea to his superior for justice is cruelly rejected, and after a brief delirium filled with unseemly language and insubordination, the sad creature dies. While Devushkin fails to grasp all the moral issues raised by this complex tale, he clearly recognizes the way the clerk Bashmachkin (his name based on a Russian word meaning shoe) is mocked by both his peers and the narrator. He naively supposes that the author has spied on him, and is amazed that his own superior has allowed such a scurrilous work to be published.

Had he been one of Dostoevskys readers, Devushkin would presumably have been much happier with the way that the younger writer presented a poor copying clerk, for in Poor People Dostoevsky clearly intended to make a polemical response to The Greatcoat. The thrust of his new, more sympathetic approach lay in the humanization of his central protagonist, along with a more realistic depiction of his situation. Gogols Bashmachkin spends the bare minimum until the purchase of the fateful greatcoat, so why is he penniless? Dostoevskys Devushkin uses most of his income either on supporting and entertaining Varvara, or on drowning his sorrows. Bashmachkins love is for a mere item of clothing, Devushkins is for a friendless orphan. Even their names are contrasting, Gogols degrading derivation from bashmak , shoe, giving way to Dostoevskys sympathetic derivation from devushka , young girl (also contrasted in the novel with the name of the odious Bykov, Mr Bull). Perhaps most importantly of all, Dostoevsky gives the humble copying clerk a voice. Bashmachkin is scarcely able to form a coherent sentence and his writing never progresses beyond the stage of copying official documents. By contrast, Devushkin, who enjoys copying works of literature too, is moreover a writer himself, the author of letters to his beloved Varvara, a man who muses on his own potential as a writer and takes pride in the development of his prose style.