2014 by Bob Welch

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc.

Published in association with the literary agency of WordServe Literary Group, Ltd., www.wordserveliterary.com

Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com

Scripture quotations marked ESV are taken from THE ENGLISH STANDARD VERSION. 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers.

Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version (public domain).

ISBN 978-1-4002-0667-4 (eBook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Welch, Bob, 1954

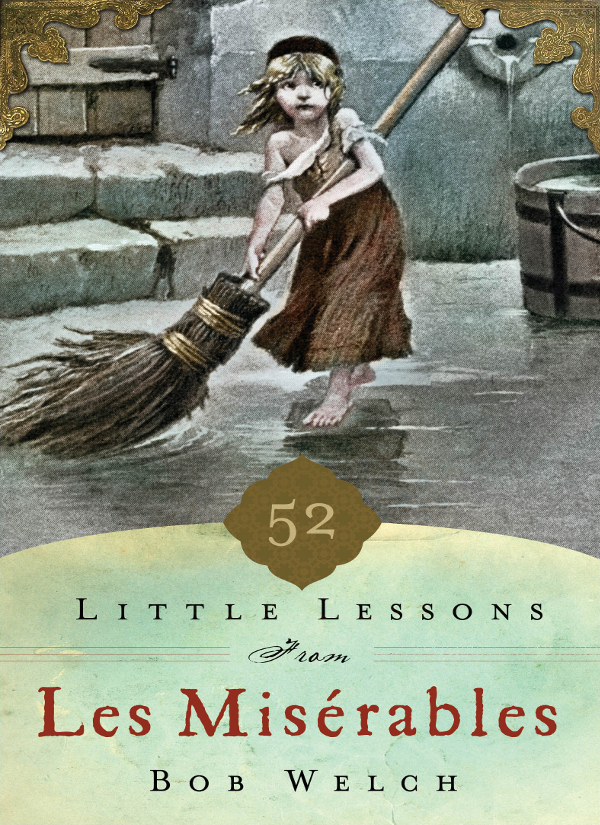

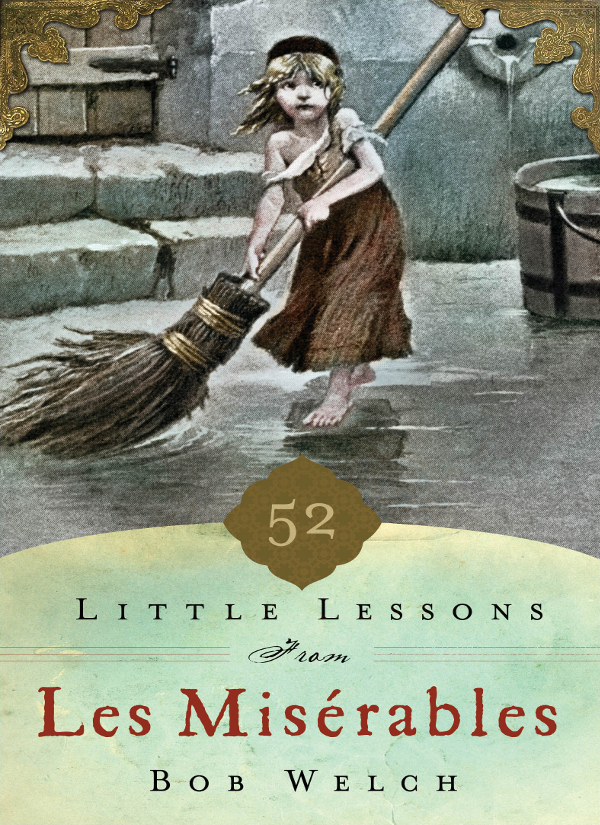

52 little lessons from Les Misrables / by Bob Welch.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4002-0666-7 (hardback)

1. Hugo, Victor, 1802-1885. Misrables. 2. Faith in literature. 3. Christianity in literature. I. Title. II. Title: Fifty-two little lessons from Les Misrables.

PQ2286.W45 2014

843.7--dc23

2014005366

14 15 16 17 18 RRD 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Les Misrables (Lay-mee-zay-rahbl)The Miserable Ones, or The Poor

PRIMARY CHARACTERS

Jean Valjean (Zhan Val-zhan)ex-convict who begins life anew while being tracked down by a tireless police inspector

Bishop Myrielcompassionate bishop whose mercy on Valjean changes the ex-convicts life (full name: Monseigneur Charles Franois-Bienvenu Myriel)

Inspector Javert (Jah-ver)letter-of-the-law police inspector whose obsession is to bring justice to Valjean

Cosette (Ko-zet)Fantines daughter, saved by Valjean from the clutches of a cruel and cunning innkeeper couple, the Thnardiers

Fantine (Fahn-teen)unmarried, working-class girl whittled to her core by poverty; mother of Cosette

Marius Pontmercy (Mar-ee-us Pohn-mair-see)idealistic student who falls in love with Cosette

The Thnardiers (Ten-are-dee-ays)husband and wife innkeepers bent on exploiting all who come near, including Cosette

OTHERS

Bamatabois (Bam-ah-tah-bwah)prospective customer whose degradation of Fantine triggers her wrath

Champmathieu (Chomp-mot-two)poor, uneducated man who is identified, tried, and almost convicted as being Jean Valjean

Enjolras (Ahn-jol-rahs)leader of the student revolutionary group Friends of the ABC (ah bay say), so-named from a play on the French word abaisss (the lowly or abased)

ponine (Epp-oh-neen)daughter of the Thnardiers who secretly loves Marius and redeems herself with that love

Fauchelevent (Fosh-luh-vohn)man saved by Valjean in Montreuil-sur-Mer who later helps Valjean in a Paris convent

Gavroche (Gav-rosh)likable street urchinand son of the Thnardierswho gives his all to the student revolutionary cause

Gillenormand (He-lare-nor-ma)Mariuss grandfather, a devout monarchist and self-seeking part of Pariss bourgeois class

Madeleine (Mad-eh-lenn)name Valjean assumes when he comes to Montreuil-sur-Mer

Petit Gervaistwelve-year-old boy from whom Valjean steals a coin

Colonel Georges Pontmercy (Zhorzh Pohn-mair-see)Mariuss father, a courageous officer of Napolons who grudgingly allows Mariuss grandfather to bring up his son

Flix Tholomys (Thol-o-mee-es)college student in Paris who abandons Fantine after getting her pregnant

PLACES

Digne (Din-yay)town in French Alps where Valjean meets the bishop

Montfermeil (Moan-fer-may)town where the Thnardiers and Cosette live

Montreuil-sur-Mer (Mon-twee-soor-Mair)town where Valjean assumes the name Madeleine and begins anew

Petit-Picpus (Pet-teet-Pic-poo)convent in Paris where Valjean and Cosette live

Toulon (Too-lohn)prison on coast of southern France where Valjean spends nineteen years

THE FIRST QUESTION YOU ASK YOURSELF WHEN BEGINNING the challenge of conveying the life lessons of Les Misrables is: Really? You couldnt have chosen a less complex story, one not based on a book whose unabridged Signet paperback edition stretches to 1,463 pages?

Les Misrables etches Hugos view of the world so deeply in the mind that it is impossible to be the same person after reading it, writes Graham Robb in Victor Hugo: A Biography. [And] not just because it takes a noticeable percentage of ones life to read it.

The second questionassuming youve considered the first and, as I do, believe the richness of the story outweighs the task of plowing through a brick-thick bookis: On what will you base such lessons?

Should you base them on Victor Hugos 1862 work, considered by many to be the greatest social novel of all time? On the musical, the worlds longest running, and seen by more than sixty-five million people in forty-two countries? Or on the more than thirty movie versions, the latest of which, in 2012, garnered eight Academy Award nominations and won a Golden Globe award for best picture?

If, over a century and a half, Les Misrables has evolved into something of an artistic trinity, it would seem appropriate to respect it as such. Although Hugos original story will be the foundation on which I build, each of the three incarnations is unique and worthy on its own. Taken as a whole, they provide a grand expression of how Hugo himself describes his story: a progress from evil to good, from injustice to justice, from falsehood to truth, from night to day, from appetite to conscience, from corruption to life; from bestiality to duty, from hell to heaven, from nothingness to God.

To read Hugos words is to see the brushstrokes of an artist creating a literary masterpiece; to watch the musical, first done in 1980 in Paris, is not only to hear and see Les Miz but to feel it as if youre sitting in an emotional wind tunnel; and, finally, to watch the 2012 movie is not only to surprise yourself at having loved an entire sung-through movie but also to marvel at the fascinating blend of nineteenth-century France and twenty-first-century moviemaking technology.

As these three streams tumble down through time, the inspirational lake they create can speak to us all. Hugo writes:

I dont know whether it will be read by everyone, but it is meant for everyone... Social problems go beyond frontiers. Humankinds wounds, those huge sores that litter the world, do not stop at the blue and red lines drawn on maps. Wherever men go in ignorance or despair, wherever women sell themselves for bread, wherever children lack a book to learn from or a warm hearth, Les Misrables knocks at the door and says: open up, I am here for you.

I analyze Hugos work not as a Les Misrables expert but as a fellow life traveler smitten with the story and as a firm believer that one of the gifts of great literature, theater, and movies is self-discovery. The question shouldnt be only, what did the story say about France back then? But also, what can it say to me where I am right now?

I came to love Les Miz late, not as a decades-long fan or drama critic, but as a journalist and author fascinated by the twining of life and faith, having written, among sixteen other books,

Next page