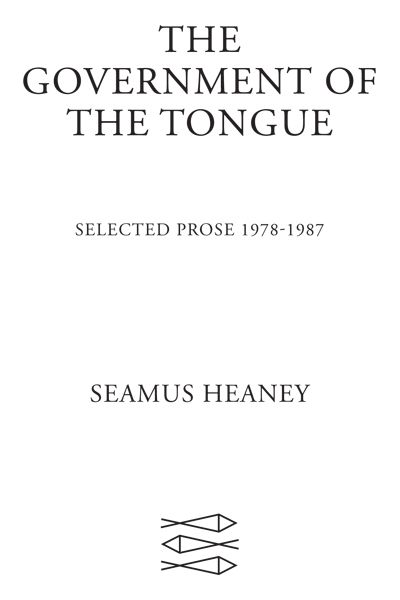

Seamus Heaney - The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987

Here you can read online Seamus Heaney - The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1990, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:1990

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In this volume of critical essays, Seamus Heaney scrutinizes the poetry of many masterful poets. Throughout the collection, Heaneys gifts as a wise and genial reader are exercised with characteristic exactness, and we are reminded, above all, of the essentially gratifying nature of poetry itself.

The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Charles Monteith

Acknowledgements

The second part of this book consists of the T. S. Eliot Memorial Lectures, delivered in October 1986 at Eliot College, in the University of Kent. I am grateful to Dr Shirley Barlow, Master of Eliot College, for her hospitality to my wife and myself on that occasion, which was made memorable also by the presence in the audience of Mrs Valerie Eliot; and of many friends including, in particular, the dedicatee, Charles Monteith, erstwhile assistant to T. S. Eliot, and my first editor at Faber and Faber.

The first part is made up of pieces written for or delivered upon various occasions. The introductory essay steals from Place and Displacement, originally presented as the first Pete Laver Memorial Lecture at Grasmere in 1984, and from a lecture given to the Royal Dublin Society in 1986, subsequently printed in Shenandoah as The Interesting Case of Nero, Chekhovs Cognac and a Knocker. The Placeless Heaven was the opening address at Kavanaghs Yearly, at Carrickmacross in November 1985, and was afterwards printed in the Massachusetts Review. The Main of Light appeared in Larkin at Sixty (Faber, 1982). The Murmur of Malvern (originally entitled The Language of Exile), The Fully Exposed Poem and Atlas of Civilization were published as review articles in Parnassus. The Poems of the Dispossessed Repossessed appeared in the Sunday Tribune. Sounding Auden and Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam were published in the London Review of Books. The Impact of Translation was a contribution to the 1986 conference of the English Institute and was printed in the Yale Review. Lowells Command appeared in Salmagundi.

In the course of the first of the Eliot Memorial Lectures, I pirated a few pages from my Envies and Identifications: Dante and the Modern Poet ( Irish University Review, Spring, 1985); and in the course of the third one, I culled sentences from my contribution to the 1979 MLA symposium on Current Unstated Assumptions About Poetry ( Critical Inquiry, Summer, 1981). Every one of the pieces has undergone revisions, mostly for stylistic reasons, but sometimes in order to shed material more appropriate to the original occasion than to the context of this book.

I am indebted as ever to friends and colleagues: Helen Vendler, Frank Bidart and Bernard McCabe read several parts of the manuscript and helped me to get some things into more exact language. To Nancy Williston, who performed the feat of transmitting the contents of innumerable rewritten, handwritten pages into the serviceable memory of a word-processor, I am grateful for unfailing good humour and valiant persistence at the keyboard.

The Interesting Case of Nero, Chekhovs Cognac and a Knocker

In 1972, in Belfast, I had an arrangement one evening to meet my friend, the singer David Hammond. We were to assemble in a recording studio in order to put together a tape of songs and poems for a mutual friend in Michigan. The tape was to be sent in memory of a party which the man from Michigan had attended some months beforehand, when tunes and staves had been uttered with great conviction. The occasion had been immensely enjoyable and the whole point of the tape was to promote that happiness and expansiveness which song, meaning both poetry and music, exists to promote in the first place.

In the event, we did not actually make the tape. On our way to the studio, a number of explosions occurred in the city and the air was full of the sirens of ambulances and fire engines. There was news of casualties. A certain half-directed fury was evident behind the ministrations of the loyalist BBC security men who checked us in. There was no sense of what to anticipate. And still that implacable disconsolate wailing of the ambulances continued.

It was music against which the music of the guitar that David unpacked made little impression. So little, indeed, that the very notion of beginning to sing at that moment when others were beginning to suffer seemed like an offence against their suffering. He could not raise his voice at that cast-down moment. He packed the guitar again and we both drove off into the destroyed evening.

* * *

I begin with this story because it dramatizes a tension which is the underlying subject of many of the pieces in this book. It is a tension to which all artists are susceptible, just as the children of temperamentally opposed parents are susceptible. The child in this case is the poet, and the parents are called Art and Life. Both Art and Life have had a hand in the formation of any poet, and both are to be loved, honoured and obeyed. Yet both are often perceived to be in conflict and that conflict is constantly and sympathetically suffered by the poet. He or she begins to feel that a choice between the two, a once-and-for-all option, would simplify things. Deep down, of course, there is the sure awareness that no such simple solution or dissolution is possible, but the waking mind desires constantly some clarified allegiance, without complication or ambivalence.

Perhaps Art and Life sound a little distant, so let us put it more melodramatically and call them Song and Suffering. What David Hammond and I were experiencing, at a most immediate and obvious level, was a feeling that song constituted a betrayal of suffering. To go back even further to an archetypal if cartoonish version of the same situation: if we had played and sung and said poems, we would have been following the example of the singer and player Nero, who notoriously fiddled while Rome burned. Neros action has ever since been held up as an example of human irresponsibility, if not callousness; conventionally, it represents an abdication from the usual instinctive need which a human being feels in such situations to lament, if not to try to prevent, the fate of the stricken; proverbially, it has come to stand for actions which are frivolous to the point of effrontery, and useless to the point of insolence. Nobody has a good word to say for Nero, it would seem. And nobody, it would seem, could blame Hammond and myself for clamming up in earshot of the sirens: to have sung and said the poems in those conditions would have been a culpable indulgence.

Or would it? Why should the joyful affirmation of music and poetry ever constitute an affront to life? One answer is, of course, that there can be a complacency and an insulation from reality in some song and some art, which in itself constitutes the affront. This perception of the mystification which Art can involve was notoriously enforced upon those poets who experienced the gap between reality and rhetoric in the trenches of Flanders during the First World War, and it is from this moment in our century that radiant and unperturbed certitudes about the consonance between the true and the beautiful become suspect. The locus classicus for all this is in the life and poetry of Wilfred Owen, the young English poet who died at the front in 1918. Ever since Edmund Blunden published his edition of the poems and his memoir of Owen in 1931, this brave and tender poet has haunted the back of the literary mind as a kind of challenge. The challenge is voiced simply by Geoffrey Hill in these lines:

Must men stand by what they write

as by their camp beds or their weaponry

or shell-shocked comrades while they sag and cry?

The fact that Hills question is couched in terms of a First World War vocabulary makes it all the more apposite. Should you write something you are not prepared to live or, in extremis, die for? What did Horace mean when he wrote the lines dulce et decorum est pro patria mori? It is sweet and right to die for your fatherland? What, Owen asks even more savagely, does the twentieth-century poet mean who repeats this kind of consoling and mystifying rhetoric at a safe distance from the front where the actual dying takes place? His poems were meant to outrage rather than console. They were written out of the shock of the deception incurred by conventional artistic expression in particular, the expression of the notion that dying for your country is beautiful. In a preface which would not see the light until after his own death a week before armistice in 1918, Owen affirmed that his poems would have nothing to do with this complacent, acceptable version of the beautiful which he contemptuously calls Poetry. The whole thing is passionately anti-heroic:

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987»

Look at similar books to The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.