Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Published by arrangement with W. W. Norton & Co. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

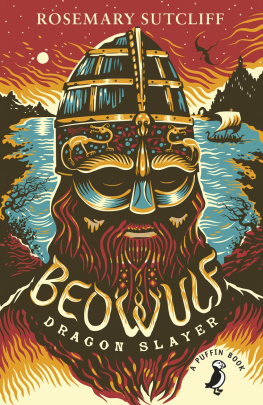

Beowulf. English & English (Old English)

Beowulf / [translated by] Seamus Heaney.1st ed.

p. cm.

Text in English and Old English.

1.

HeroesScandinaviaPoetry. 2. Epic poetry, English (Old). 3. MonstersPoetry. 4.

DragonsPoetry. I. Heaney, Seamus.

PE1583.H43 1999

829.3dc21 99-23209 The Old English text of the poem is based on Beowulf, with the Finnesburg Fragment, edited by C. L. Wrenn and W. F.

Bolton (University of Exeter Press, 1988), and is printed here by kind permission of W. F. Bolton and the University of Exeter Press. A Note on Names is reprinted here by the kind permission of W. W. Norton & Co., copyright 1999.

Introduction

And now this is an inheritance Upright, rudimentary, unshiftably planked In the long ago, yet willable forward Again and again and again.

BEOWULF: THE POEM The poem called Beowulf was composed sometime between the middle of the seventh and the end of the tenth century of the first millennium, in the language that is to-day called Anglo-Saxon or Old English. It is a heroic narrative, more than three thousand lines long, concerning the deeds of a Scandinavian prince, also called Beowulf, and it stands as one of the foundation works of poetry in English. The fact that the English language has changed so much in the last thousand years means, however, that the poem is now generally read in translation and mostly in English courses at schools and universities. This has contributed to the impression that it was written (as Osip Mandelstam said of The Divine Comedy ) on official paper, which is unfortunate, since what we are dealing with is a work of the greatest imaginative vitality, a masterpiece where the structuring of the tale is as elaborate as the beautiful contrivances of its language. Its narrative elements may belong to a previous age but as a work of art it lives in its own continuous present, equal to our knowledge of reality in the present time.

The poem was written in England but the events it describes are set in Scandinavia, in a once upon a time that is partly historical. Its hero, Beowulf, is the biggest presence among the warriors in the land of the Geats, a territory situated in what is now southern Sweden, and early in the poem Beowulf crosses the sea to the land of the Danes in order to clear their country of a maneating monster called Grendel. From this expedition (which involves him in a second contest with Grendels mother) he returns in triumph and eventually rules for fifty years as king of his homeland. Then a dragon begins to terrorize the countryside and Beowulf must confront it. In a final climactic encounter, he does manage to slay the dragon, but he also meets his own death and enters the legends of his people as a warrior of high renown. We know about the poem more or less by chance because it exists in one manuscript only.

This unique copy (now in the British Library) barely survived a fire in the eighteenth century and was then transcribed and titled, retranscribed and edited, translated and adapted, interpreted and reinterpreted, until it has become canonical. For decades it has been a set book on English syllabuses at university level all over the world. The fact that many English departments require it to be studied in the original continues to generate resistance, most notably at Oxford University, where the pros and cons of the inclusion of part of it as a compulsory element in the English course have been debated regularly in recent years. For generations of undergraduates, academic study of the poem was often just a matter of construing the meaning, getting a grip on the grammar and vocabulary of Anglo-Saxon, and being able to recognize, translate, and comment upon random extracts which were presented in the examinations. For generations of scholars too the interest had been textual and philological; then there developed a body of research into analogues and sources, a quest for stories and episodes in the folklore and legends of the Nordic peoples which would parallel or foreshadow episodes in Beowulf . Scholars were also preoccupied with fixing the exact time and place of the poems composition, paying minute attention to linguistic, stylistic, and scribal details.

More generally, they tried to establish the history and genealogy of the dynasties of Swedes and Geats and Danes to which the poet makes constant allusion; and they devoted themselves to a consideration of the world-view behind the poem, asking to what extent (if at all) the newly Christian understanding of the world which operates in the poets designing mind displaces him from his imaginative at-homeness in the world of his poema pagan Germanic society governed by a heroic code of honour, one where the attainment of a name for warrior-prowess among the living overwhelms any concern about the souls destiny in the afterlife. However, when it comes to considering Beowulf as a work of literature, there is one publication that stands out. In 1936, the Oxford scholar and teacher J.R.R. Tolkien published an epoch-making paper entitled Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics which took for granted the poems integrity and distinction as a work of art and proceeded to show in what this integrity and distinction inhered. He assumed that the poet had felt his way through the inherited materialthe fabulous elements and the traditional accounts of an heroic pastand by a combination of creative intuition and conscious structuring had arrived at a unity of effect and a balanced order. He assumed, in other words, that the Beowulf poet was an imaginative writer rather than some kind of back-formation derived from nineteenth-century folklore and philology.

Tolkiens brilliant literary treatment changed the way the poem was valued and initiated a new eraand new termsof appreciation. It is impossible to attain a full understanding and estimate of Beowulf without recourse to this immense body of commentary and elucidation. Nevertheless, readers coming to the poem for the first time are likely to be as delighted as they are discomfited by the strangeness of the names and the immediate lack of known reference points. An English speaker new to The Iliad or The Odyssey or The Aeneid will probably at least have heard of Troy and Helen, or of Penelope and the Cyclops, or of Dido and the golden bough. These epics may be in Greek and Latin, yet the classical heritage has entered the cultural memory enshrined in English so thoroughly that their worlds are more familiar than that of the first native epic, even though it was composed centuries after them. Achilles rings a bell, but not Scyld Scfing.

Ithaca leads the mind in a certain direction, but not Heorot. The Sibyl of Cumae will stir certain associations, but not bad Queen Modthryth. First-time readers of Beowulf very quickly rediscover the meaning of the term the dark ages, and it is in the hope of dispelling some of the puzzlement they are bound to feel that I have added the marginal glosses which appear in the following pages. Still, in spite of the sensation of being caught between a shield-wall of opaque references and a word-hoard that is old and strange, such readers are also bound to feel a certain shock of the new. This is because the poem possesses a mythic potency. Like Shield Sheafson (as Scyld Scfing is known in this translation), it arrives from somewhere beyond the known bourne of our experience, and having fulfilled its purpose (again like Shield), it passes once more into the beyond.