First Mariner Books edition 2009

Copyright 2008 by Deanne Stillman

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Stillman, Deanne.

Mustang : the saga of the wild horse in the American West / Deanne Stillman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-618-45445-7

ISBN 978-0-547-23791-6 (pbk.)

1. MustangHistory. 2. West (U.S.)History. I. Title.

SF 293. M 9 S 75 2008

599-665'50978dc22 2008004732

Passages from this book first appeared in the Los Angeles Times, LA Weekly, 111 Magazine, the Boston Globe, and the Chronicle of the Horse; on slate.com, world-hum.com, newwest.net, and huffingtonpost.com; and in the anthologies Naked: Writers Uncover the Way We Live on Earth and Unbridled: The Western Horse in Fiction and Nonfiction.

The author is grateful for permission to quote from The Misfits by Arthur Miller. Copyright 1957 by Arthur Miller, reprinted with permission of The Wylie Agency, Inc.

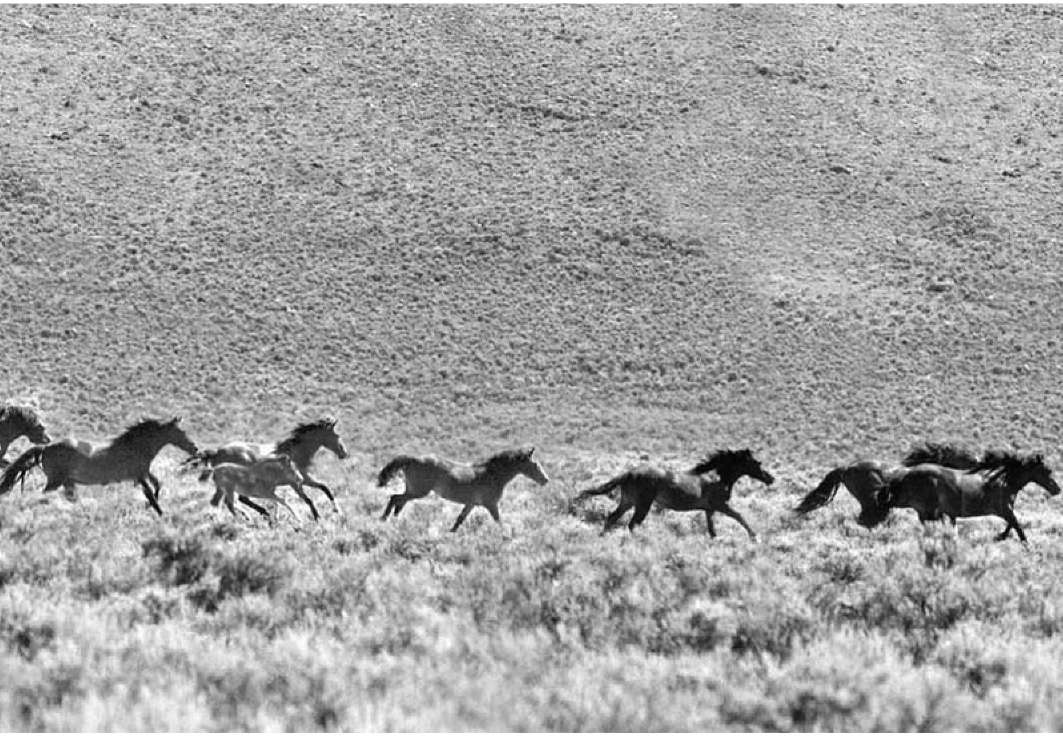

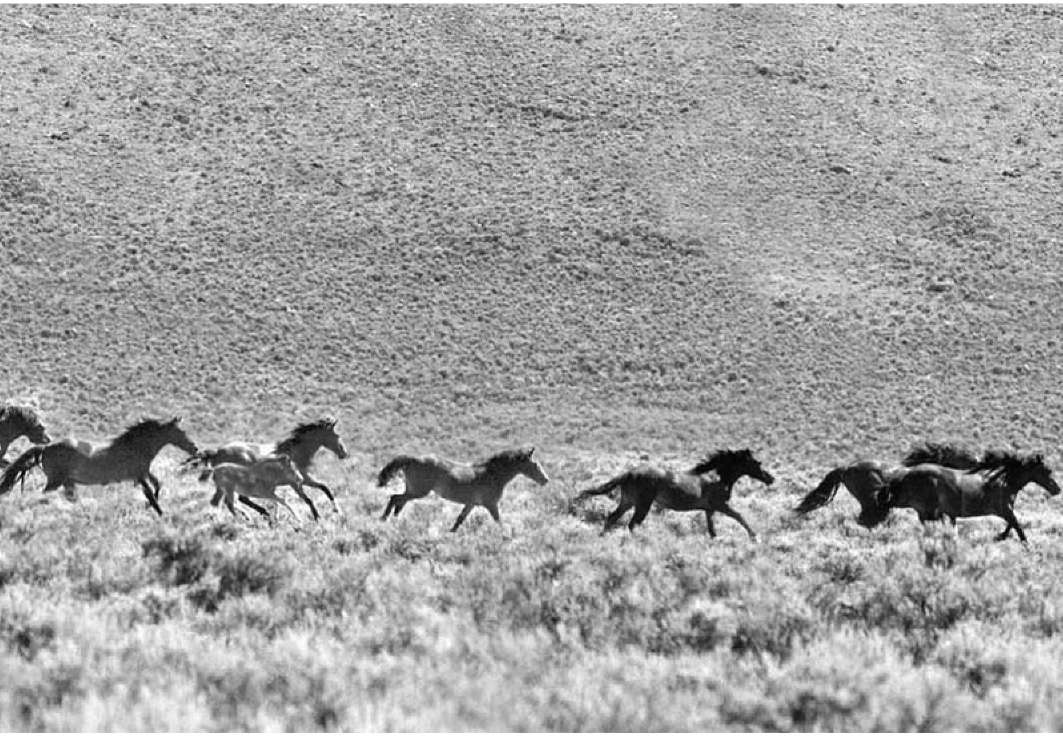

PHOTO CREDITS : Frontispiece: Challisherd, central Idaho, Elissa Kline (2005 All Rights Reserved); : Library of Congress; back photo: LRTC Wild Horse Mentors

e ISBN 978-0-547-52613-3

v2.0914

This book is dedicated to my mother, Eleanor Stillman, a free spirit, and to my sister, Nancy Stillman, who understood the magic of horses before I did

Introduction

FOR A LONG TIME, the American desert has been my beat and my passion. The reasons are many, but really, there is only one. In the desert, the chatter of city life fades away and my own thoughts vanish; I get quiet and I hear things. The beating of wings. The scratching of lizard. The crack of tortoise egg. The whisper of stories that want to be told.

In 1991, I walked into a bar on Highway 62, the desert two-lane that stretches from Interstate 10 in California eastward into the far Mojave. I had just finished a hike in Joshua Tree National Park. It was twilight. Thunderclouds were rolling in, and the perfume of creosote was in the air. Inside the Josh Lounge, people sat at the bar, guarding their pitchers of beer, talking of sports, the weather, local news. After a while, I heard the first few notes of a dark desert tale. Two girls had been sliced up by a Marine, someone said; probably they deserved it. Who were they? I asked. Just some trash came the reply. I sought more information but people shrugged and then someone punched the jukebox and Dirty White Boy came on and the conversation was over. A frequent visitor to the area, I knew something about the girls who took care oflocal members of the military, and I vowed to bear witness to their story. A decade later, it became my book Twentynine Palms: A True Story of Murder, Marines, and the Mojave.

But before I was finished, another terrible tale was unfolding and I couldnt shake off its call. A few days after Christmas in 1998, I was waiting to meet with a source in another desert bar. I picked up the local paper and read that six wild horses had been gunned down in the mountains outside Reno. The next day, the body count had grown to twenty. By the end of December, thirty-four dead mustangs had been found in the Virginia Range, and the hideous news was announced to the world on the ticker tape at Times Square. A few days later, three men were arrested. Two of them were Marines and one of them was stationed at Twentynine Palms.

I was surprisedand then I wasnt. I knew that a number of grisly crimes had emanated from the military base hidden away in that remote desert town. Now, the victims were wild horses, and their story also spoke of our history, our heritage, and our land. But what exactly was their story? I wondered as the Reno incident began to take over my life. Why would someone go out and kill the animals that had blazed our trails, fought our wars, served as our most loyal partners? As I began looking into the story, I realized that what had happened to the wild horses in Reno was about much more than that particular event. It went right to the heart of who we are as Americans.

With all due respect to our official icon, the eagle, he of the broad wingspan and the ability to see across great distances, of patience born of the ages and of majestic flight, it is really the wild horse, the four-legged with the flying mane and tail, the beautiful, bighearted steed who loves freedom so much that when captured he dies of a broken heart, the ever-defiant mustang that is our true representative, coursing through our blood as he carries the eternal message of America. Many have read Moby Dick, but fewincluding me, until I began my wild horse researchremember that in his tribute to that which man should not possess, Melville devoted a passage to the other great white, the one that ranged the Great Plains:

Most famous in our Western annals and Indian traditions, is that of the White Steed of the Prairies; a magnificent milk-white charger, large-eyed, small-headed, bluff-chested, and with the dignity of a thousand monarchs in his lofty, over-scorning carriage. He was the elected Xerxes of vast herds of wild horses, whose pastures in those days were only fenced by the Rocky Mountains and the Alleghenies... The flashing cascade of his mane, the curving comet of his tail, invested him with housings more resplendent than gold- and silverbeaters could have furnished him.

As I read this passage in light of the horse killings, I started to wonder about the men who would do such a thing. Were they modern Ahabs? Or were they more prosaicjust a bunch of drunks with guns? Or perhaps they were a strange new iteration of the American psycho, or maybe even some sort of full-on combination platter of all of the above?

To see this killing for what it was, I realized, I needed to learn the story of the wild horse before the Reno massacrethe facts of its life along the trail, at war, at play, in our literature and lore, how it got here and where it came from. This was a large and at times daunting endeavor but one that I felt compelled to undertake. Quite simply, the horse deserved its own account, and no such thing existedat least not in the way I wanted to tell it, by traveling with the horse across space and time, right through the entire American saga.

Then, also, there was a personal connection. Years ago, when my parents got divorced, my mother, sister, and I moved from an upper-middle-class suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, to a blue-collar community. Suddenly, most of our friends in the old neighborhoodand even some relativesstopped talking to us, and it didnt take long to figure out that our new address had made us social pariahs. In addition, my mother had become the breadwinner in an era when there were few jobs for women outside of the secretarial pool. Typing wasnt an option because she didnt know how, but she did have another skill that, due to her persistence and desire, was something she could transform into a living. It was riding a horse.

Soon after our move, she got a job as what was then called exercise boy at the racetrack. There were few women working in that capacity at the time (we later found out that she may have been the first in the country to do so); among those women who tried out for the job, most didnt qualify for various reasons or were not given the chance to prove themselves. After all, the job wasnt called exercise boy for nothing. But my mother was an expert equestrienne; shed ridden with the local hunt club and shown her own horses on the competitive circuit, impressing the local gentry and winning many prizes. And so her skills did not go unnoticed at the track and she quickly became the talk of northeastern Ohio.

Next page