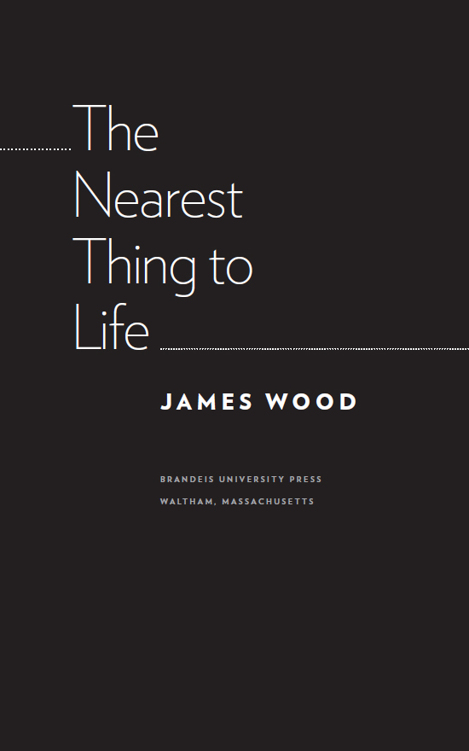

THE MANDEL LECTURES IN THE HUMANITIES AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY

Sponsored by the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation

Faculty Steering Committee for the Mandel Center for the Humanities

Ramie Targoff, chair

Brian M. Donahue, Talinn Grigor, Fernando Rosenberg, David Sherman, Harleen Singh, Marion Smiley

Former Members

Joyce Antler, Steven Dowden, Sarah Lamb, Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Eugene Sheppard, Jonathan Unglaub, Michael Willrich, Bernard Yack

The Mandel Lectures in the Humanities were launched in the fall of 2011 to promote the study of the humanities at Brandeis University, following the 2010 opening of the new Mandel Center for the Humanities. The lectures bring to the Mandel Center each year a prominent scholar who gives a series of three lectures and conducts an informal seminar during his or her stay on campus. The Mandel Lectures are unique in their rotation of disciplines or fields within the humanities and humanistic social sciences: the speakers have ranged from historians to literary critics, from classicists to anthropologists. The published series of books therefore reflects the interdisciplinary mission of the center and the wide range of extraordinary work being done in the humanities today.

For a complete list of books that are available in the series,

visit www.upne.com

JAMES WOOD, The Nearest Thing to Life

DAVID NIRENBERG, Aesthetic Theology and Its Enemies: Judaism in Christian Painting, Poetry, and Politics

Brandeis University Press

An imprint of University Press of New England

www.upne.com

2015 James Wood

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wood, James, 1965

The nearest thing to life / James Wood.

pages cm.(Mandel Center for the Humanities lectures)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61168-741-5 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61168-742-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61168-743-9 (ebook)

1. Wood, James, 1965 2. CriticsGreat BritainBiography.

I. Title.

PR 55.W55A3 2015

801'.95092dc23 2014035115

For C. D. M.

and in memory of

Sheila Graham Wood

(19272014)

Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.

GEORGE ELIOT

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Why?

I

Recently, I went to the memorial service of a man I had never met. He was the younger brother of a friend of mine, and had died suddenly, in the middle of things, leaving behind a wife and two young daughters. The program bore a photograph, above his compressed dates (19682012). He looked ridiculously young, blazing with lifesquinting in bright sunlight, and smiling slightly as if he were just beginning to get the point of someones joke. In some terrible way, his death was the notable, the heroic fact of his short life; all the rest was the usual joyous ordinariness, given testament by various speakers. Here he was, jumping off a boat into the Maine waters; here he was, as a child, larkily peeing from a cabin window with two young cousins; here he was, living in Italy and learning Italian by flirting; here he was, telling a great joke; here he was, an ebullient friend, laughing and filling the room with his presence. As is generally the case at such final celebrations, speakers struggled to expand and hold the beautifully banal instances of a life, to fill the dates between 1968 and 2012, so that we might leave the church thinking not of the first and last dates but of the dateless minutes in between.

It is an unusual and in some ways unnatural advantage to be able to survey the span of someone elses life, from start to finish. Such surveillance seems peremptory, high-handed, forward. Grief does not seem entitlement enough for the arrogation of the divine powers of beginning and ending. We are uneasy with such omniscience. We do not possess it with regard to our own lives, and we do not usually seek it with regard to the lives of others.

But if this ability to see the whole of a life is godlike, it also contains within itself the beginning of a revolt against God: once a life is contained, finalized, as if flattened within the pages of a diary, it becomes a smaller, contracted thing. It is just a life, one of millions, as arbitrary as everyone elses, a named tenancy that will soon become a nameless one; a life that we know will be thoroughly forgotten within a few generations, like our own. At the very moment we play at being God, we also work against God, hurl down the script, refuse the terms of the drama, appalled by the meaninglessness and ephemerality of existence. Death gives birth to the first questionWhy?and kills all the answers. And how remarkable, that this first question, the word we utter as small children when we first realize that life will be taken away from us, does not change, really, in depth or tone or mode, throughout our lives. It is our first and last question, uttered with the same incomprehension, grief, rage, , but everyone is alive, and that really also means everyone is dead.

The Why? question is a refusal to accept death, and is thus a theodicean question: it is the question that, in the long history of theology and metaphysics, has been answeredor shall we say, replied toby theodicy, the formal term for the attempt to reconcile the suffering and the meaninglessness of life with the notion of a providential, benign, and powerful deity. Theodicy is a project at times ingenious, bleak, necessary, magnificent, and platitudinous. There are many ways to turn around and around the stripped screw of theological justification, from Augustines free-will defense to the heresy of Gnosticism; from Gods majestic bullying of Job (be quiet and know my unspeakable power) to Dostoyevskys realization that there is no answer to the Why? question except through the love of Christembodied in Alyoshas kiss of his brother, and Father Zosimas saintliness. But these belong to the literary and theological tradition. The theodicean question is also being uttered every day, far from such grand or classic statements, and the theodicean answer is offered every day, toowith clumsy love, with optimistic despair, with cursory phlegm, by any parent who has had to tell a child that perhaps life does indeed continue in heaven, or that Gods ways are not our own, or that Daddy and Mummy simply dont know why such things happen. If the theodicean question does not change throughout a lifetime, so the theodicean answers have not changed, essentially, in three millennia: Gods reply to Job is as radically unhelpful as the parent who replies to little Annies anguished questions by telling her to be quiet and go read a book. All of us still live within this question and live within these fumbled answers.

When I was a child, the Why? question was acute, and had a religious inflection. I grew up in an intellectual household that was also a religious one, and with the burgeoning apprehension that intellectual and religious curiosity might not be natural allies. My father was a zoologist who taught at Durham University, my mother a schoolteacher at a local girls school. Both parents were engaged Christians; my mother came from a Scottish family with Presbyterian and evangelical roots. The scriptures saturated everything. My father called my relationship with my first girlfriend unedifying (though in order to deliver this baleful, Kierkegaardian news, he had to ambush me in the car, so that he could avoid catching my eye). I was discouraged from using the suspiciously secular term good luck, and encouraged to substitute it with the more providential blessing. One was blessed to do well in school exams, blessed to have musical talent, blessed to have nice friends, and, alas, blessed to go to church. My untidy bedroom, said my mother, was an example of poor stewardship. Dirty laundry was somehow un-Christian.

Next page