Table of Contents

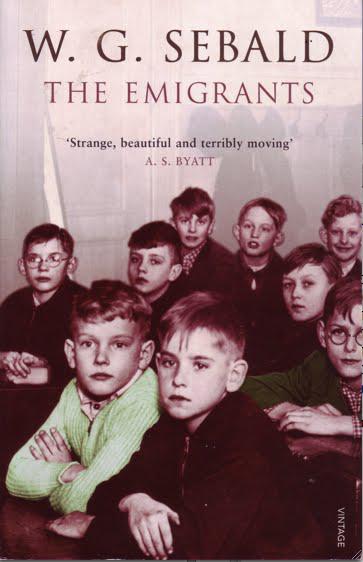

The Emigrants

W. G. Sebald

Translated by

MICHAEL HULSE

DR. HENRY SELWYN

And the last remnants memory destroys

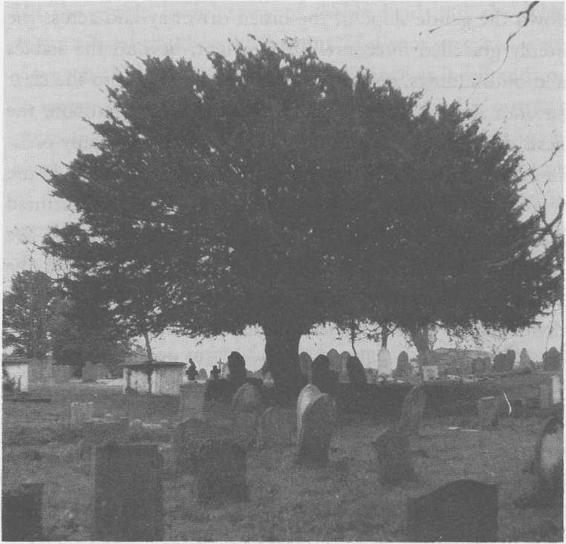

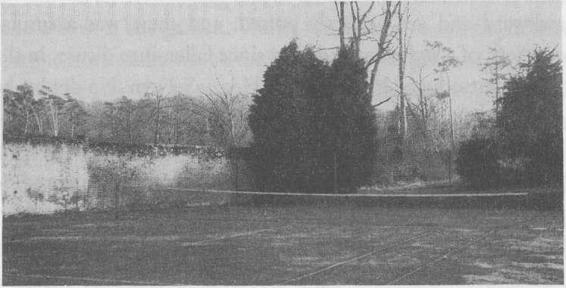

At the end of September 1970, shortly before I took up my position in Norwich, I drove out to Hingham with Clara in search of somewhere to live. For some 25 kilometres the road runs amidst fields and hedgerows, beneath spreading oak trees, past a few scattered hamlets, till at length Hingham appears, its asymmetrical gables, church tower and treetops barely rising above the flatland. The market place, broad and lined with silent facades, was deserted, but still it did not take us long to find the house the agents had described. One of the largest in the village, it stood a short distance from the church with its grassy graveyard, Scots pines and yews, up a quiet side street. The house was hidden behind a two-metre wall and a thick shrubbery of hollies and Portuguese laurel. We walked down the gentle slope of the broad driveway and across the evenly gravelled forecourt. To the right, beyond the stables and outbuildings, a stand of beeches rose high into the clear autumn sky, its rookery deserted in the early afternoon, the nests dark patches in a canopy of foliage that was only occasionally disturbed. The front of the large, neoclassical house was overgrown with Virginia creeper. The door was painted black and on it was a brass knocker in the shape of a fish. We knocked several times, but there was no sign of life inside the house. We stepped back a little. The sash windows, each divided into twelve panes, glinted blindly, seeming to be made of dark mirror glass. The house gave the impression that no one lived there. And I recalled the chateau in the Charente that I had once visited from Angoulme. In front of it, two crazy brothers - one a parliamentarian, the other an architect - had built a replica of the facade of the palace of Versailles, an utterly pointless counterfeit, though one which made a powerful impression from a distance. The windows of that house had been just as gleaming and blind as those of the house we now stood before. Doubtless we should have driven on without accomplishing a thing, if we had not summoned up the nerve, exchanging one of those swift glances, to at least take a look at the garden. Warily we walked round the house. On the north side, where the brickwork was green with damp and variegated ivy partly covered the walls, a mossy path led past the servants' entrance, past a woodshed, on through deep shadows, to emerge, as if upon a stage, onto a terrace with a stone balustrade overlooking a broad, square lawn bordered by flower beds, shrubs and trees. Beyond the lawn, to the west, the grounds opened out into a park landscape studded with lone lime trees, elms and holm oaks, and beyond that lay the gentle undulations of arable land and the white mountains of cloud on the horizon. In silence we gazed at this view, which drew the eye into the distance as it fell and rose in stages, and we looked for a long time, supposing ourselves quite alone, till we noticed a motionless figure lying in the shade cast on the lawn by a lofty cedar in the southwest corner of the garden. It was an old man, his head propped on his arm, and he seemed altogether absorbed in contemplation of the patch of earth immediately before his eyes. We crossed the lawn towards him, every step wonderfully light on the grass. Not till we were almost upon him, though, did he notice us. He stood up, not without a certain embarrassment. Though he was tall and broad-shouldered, he seemed quite stocky, even short. Perhaps this impression came from the way he had of looking, head bowed, over the top of his gold-rimmed reading glasses, a habit which had given him a stooped, almost supplicatory posture. His white hair was combed back, but a few stray wisps kept falling across his strikingly high forehead. I was counting the blades of grass, he said, by way of apology for his absentmindedness. It's a sort of pastime of mine. Rather irritating, I am afraid. He swept back one of his white strands of hair. His movements seemed at once awkward and yet perfectly poised; and there was a similar courtesy, of a style that had long since fallen into disuse, in the way he introduced himself as Dr. Henry Selwyn. No doubt, he continued, we had come about the flat. As far as he could say, it had not yet been let, but we should have to wait for Mrs. Selwyn's return, since she was the owner of the house and he merely a dweller in the garden, a kind of ornamental hermit. In the course of the conversation that followed these opening remarks, we strolled along the iron railings that marked off the garden from open parkland. We stopped for a moment. Three heavy greys were rounding a little clump of alders, snorting and throwing up clods of turf as they trotted. They took up an expectant position at our side, and Dr. Selwyn fed them from his trouser pocket, stroking their muzzles as he did so. I have put them out to grass, he said. I bought them at an auction last year for a few pounds. Otherwise they would doubtless have gone straight to the knacker's yard. They're called Herschel, Humphrey and Hippolytus. I know nothing about their earlier life, but when I bought them they were in a sorry state. Their coats were infested with lice, their eyes were dim, and their hooves were cracked right through from standing in a wet field. But now, said Dr. Selwyn, they've made something of a recovery, and they might still have a year or so ahead of them. With that he took his leave of the horses, which were plainly very fond of him, and strolled on with us towards the remoter parts of the garden, pausing now and then and becoming more expansive and circumstantial in his talk. Through the shrubbery on the south side of the lawn, a path led to a walk lined with hazels, where grey squirrels were up to their mischief in the canopy of branches overhead. The

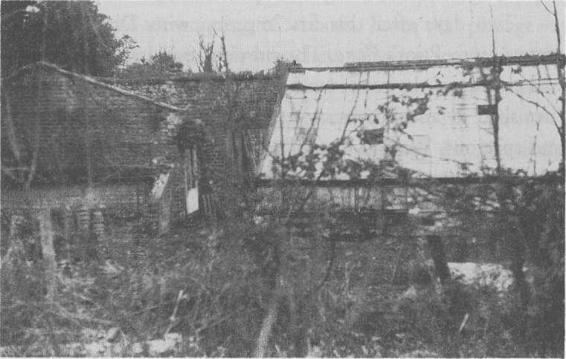

ground was thickly strewn with empty nutshells, and autumn crocuses took the weak light that penetrated the dry, rustling leaves. The hazel walk led to a tennis court bounded by a whitewashed brick wall. Tennis, said Dr. Selwyn, used to be my great passion. But now the court has fallen into disrepair, like so much else around here. It's not only the kitchen garden, he continued, indicating the tumble-down Victorian greenhouses and overgrown espaliers, that's on its last legs after years of neglect. More and more, he said, he sensed that

Nature itself was groaning and collapsing beneath the burden we placed upon it. True, the garden, which had originally been meant to supply a large household, and had indeed, by dint of skill and diligence, provided fruit and vegetables for the table throughout the entire year, was still, despite the neglect, producing so much that he had far more than he needed for his own requirements, which admittedly were becoming increasingly modest. Leaving the once well-tended garden to its own devices did have the incidental advantage, said Dr. Selwyn, that the things that still grew there, or which he had sown or planted more or less haphazardly, possessed a flavour that he himself found quite exceptionally delicate. We walked between beds of asparagus with the tufts of green at shoulder height, rows of massive artichoke plants, and on to a small group of apple trees, on which there were an abundance of red and yellow apples. Dr. Selwyn placed a dozen of these fairy-tale apples, which really did taste better than any I have eaten since, on a rhubarb leaf, and gave them to Clara, remarking that the variety was aptly named Beauty of Bath.

Next page