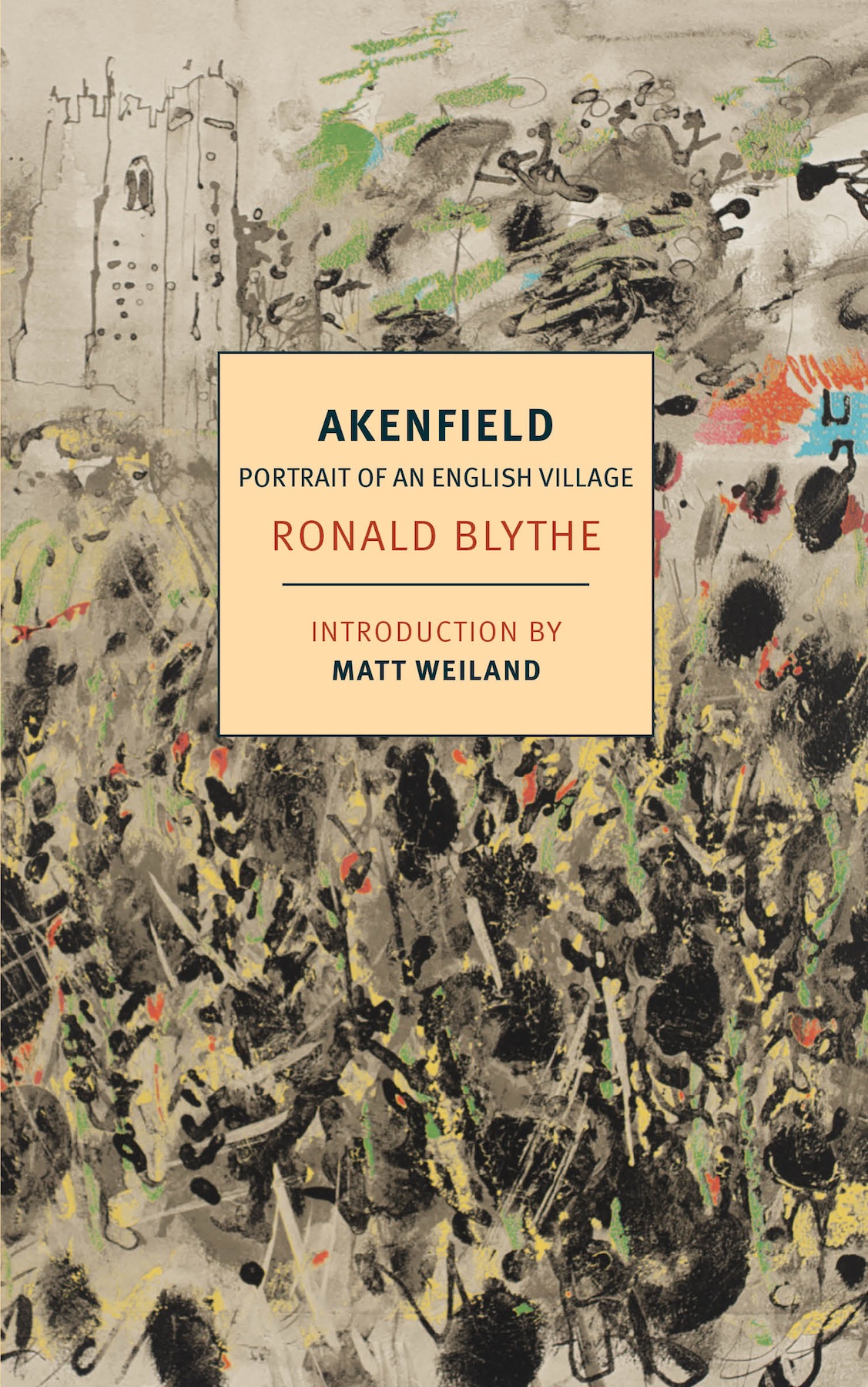

RONALD BLYTHE was born in 1922 in Suffolk, England, where his family has lived for centuries. He is the author of some thirty books including works of fiction, criticism, memoir, and social history, and has served as editor for a number of novels, poetry anthologies, and diaries. For the past twenty years he has written a weekly column for the Church Times about daily life in the Suffolk village of Wormingford, where he lives. He is the president of the John Clare Society and in 2006 received a lifetime achievement award from the Royal Society of Literature.

MATT WEILAND is a vice president and senior editor at W.W. Norton & Company. A former editor at Granta and The Paris Review, he is also the co-editor, with Sean Wilsey, of State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, Bookforum, The New Republic, and The Nation, and he contributed the introduction to the NYRB Classics edition of Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States by George R. Stewart.

AKENFIELD

Portrait of an English Village

RONALD BLYTHE

Introduction by

MATT WEILAND

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1969, 1999 by Ronald Blythe

Introduction copyright 2015 by Matt Weiland

All rights reserved.

Cover image: John Piper, Horham, Suffolk, 1975; 2015 Piper Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London; photograph 2014 Tate, London

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blythe, Ronald, 1922

Akenfield : portrait of an English village / by Ronald Blythe ; introduction by Matt Weiland.

pages cm. (New York Review Books classics)

Originally published: 1969.

ISBN 978-1-59017-830-0 (alk. paper)

1. VillagesEnglandSuffolk. 2. Suffolk (England)Social life and customs. 3. Suffolk (England)Biography. I. Title.

DA670.S9B59 2015

942.6'4dc23

2014042913

ISBN 978-1-59017-831-7

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

First published in 1969, Ronald Blythes Akenfield is an enormously vivid and affecting portrait of life in one village in the southeast of England, as told through the voices of the farmers, workers, and villagers themselves. Blythe, a novelist who had edited editions of Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy for the Penguin Classics series, chose Akenfield as a pseudonym for a village in the East Anglian county of Suffolk, where he had grown up. He spent the winter of 196667 in what he called a kind of natural conversation with all three generations of his neighbors, capturing their thoughts on farming, education, welfare, class, religion and indeed life and death. The best-selling book that resulted captured the changing nature of English rural life, and it has remained in print in England ever since as a Penguin Modern Classic.

Akenfield was also greeted enthusiastically in America, receiving rave reviews from John Updike, Paul Fussell, John Leonard, and, in The New York Times, Jan Morris (then still writing as James). It is a brilliant and extraordinary book. Its effect is one of astonishing immediacy, Morris wrote. It is as if those country people have looked up for a moment from their plow, lawnmower, or kitchen sink, and are talking directly (and disturbingly frankly) to the reader. In The New Yorker, Updike declared Akenfield to be exquisite and a wonderful book. In December 1969, The New York Times selected it as one of its twelve best books of the year, along with such epochal titles as Dean Achesons Present at the Creation, Erik H. Eriksons Gandhis Truth, Philip Roths Portnoys Complaint, and Kurt Vonneguts Slaughterhouse-Five.

Tellingly, many of the reviews hailed Akenfield as a classic of its kind, judiciously dodging the question of just what kind of book it might be. The original Penguin edition classified it as Sociology/Anthropology, which was fitting given its blend of popular ethnography and sociological survey. In form, it is often compared to the timeless works of Studs Terkel, another admirer of Akenfield, who hailed it as a revelatory book; or to those of Blythes lesser-known English contemporary Tony Parker, who produced a celebrated series of oral histories of British life on the margins. Like those books, Akenfield comprises a wide variety of edited monologues rendered in the distinctive styles of their speakers, and features contextualizing material in the authors own voice.

But Blythe saw it less as a work of social science or oral history than as a travel book. He described writing it as making a strange journey through a familiar land, and like George Orwells The Road to Wigan Pier or Alfred Kazins A Walker in the City, Blythes grand achievement in Akenfield is fundamentally that of the writer as eyewitness reporter, as traveler with a fresh eye and a great ear for language. These are books that ignore the question of what experience means and instead burrow deeply, richly into describing experience itself. Their writers are obsessed with the particulars of a place and the lives lived through it, with a time and the lives lived across it. They ask the deepest and most vital question, and answer it as well as any work of art can: What does it feel like to be anyone other than ourselves?

The place and the people Blythe chose to document in Akenfield couldnt have been less promising subjects for such a work. There is one thing about Suffolk folk, a sixth-generation East Anglian named Christopher Falconer says in Akenfield, and that is that they find talk terribly difficult.

Blythe himself acknowledged the challenge of what he called that famous Suffolk taciturnity, and he wrote movingly about how easy a village such as Akenfield was to miss:

The village lies folded away in one of the shallow valleys which dip into the East Anglian coastal plain. It is not a particularly striking place and says little at first meeting. It occupies a little isthmus of London (Eocene) clay jutting from Suffolks famous shelly sands, the Coralline and Red crags, and is approached by a spidery lane running off from the bit of straight, as they call it, meaning a handsome stretch of Roman road, apparently going nowhere. This road suggests one of those expensive planning errors which, although cancelled in the books, will mark the earth for ever. It is the kind of road which hurries one past a situation. Centuries of traffic must have passed within yards of Akenfield without noticing it.

As he explained years later, Blythe had been commissioned to write the book jointly by Penguin Books in the United Kingdom and Pantheon Books in the United States, as part of a series on how village life was changing around the world. When they came to me and said I should do Britain, I told them I was not a sociologist remotely, nor had I heard of the term oral history at the time. He had no idea how to get started on the task.

I was editing Hazlitt for Penguin and I quite liked this bookish thing, working in libraries and being scholarly. At some point they said, Have you started this book yet? So I went for a walk around Akenfield. It was an awful February day. The ditches were full of churning water coming through the field drains. These were partly the medieval ditches of the village, and when I looked down I could see what people had seen for centuries. I went to speak to the village nurse, a very old lady. Although I knew her very well, I soon realized I didnt know her at all. When she started speaking about her own life, another person emerged. When I got home, I was astonished, shaken really, by knowing what I now knew about her. When I wrote it down, that other person emerged: she worked in what was really an army hut, shed got a club foot (which I never put in the book because I thought it would upset her), she delivered all the children and laid out all the dead and patched people up with basically vaseline and strips of sheets. From there, I just shaped the book.... Often I hardly asked any questions at all, I just listened.