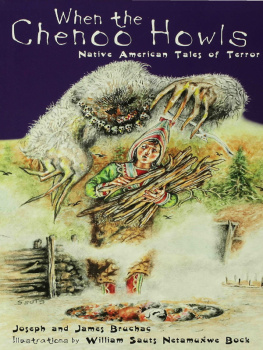

WHEN

THE

CHENOO

HOWLS

NATIVE AMERICAN TALES

OF TERROR

Joseph and James Bruchac

IllustrationsbyWilliam Sauts Netamu we Bock

we Bock

Text copyright 1998 by Joseph and James Bruchac

Illustrations copyright 1998 by William Sauts Netamu we Bock

we Bock

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

All the characters and events portrayed in this work are fictitious.

First published in the United States of America in 1998

by Walker Publishing Company, Inc.;

first paperback edition published in 1999.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry and Whiteside,

Markham, Ontario L3R 4T8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bruchac, Joseph, 1942

When the Chenoo howls: native American tales of terror/Joseph and James Bruchac; illustrations by William Sauts Netamu we Bock.

we Bock.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references

Contents: The Stone Giant (Seneca)The Flying Head (Seneca)Ugly face (Mohawk)Chenoo (Passamaquoddy)Amankamek (Lenape)Keewahkwee (Penobscot)Yakwawiak (Lenape)Man Bear (Oneida)The Spreaders (Abenaki)Aglebemu (Penobscot)Big Tree People (Onondaga)Toad Woman (Abenaki)

eISBN: 978-0-802-72130-3

1. Indians of North AmericaNortheastern

StatesFolklore. 2. Woodland IndiansFolklore.

3. TalesNortheastern States. 4. MonstersJuvenile literature.

[1. Woodland IndiansFolklore. 2. Indians of North

AmericaNortheastern StatesFolklore. 3. MonstersFolklore.

4. FolkloreNortheastern States.] I. Bruchac, James. II. Bock,

William Sauts, 1939- ill. III. Title.

E78.E2B79 1998

[398.2'089'97074]dc21 97-48715

CIP

AC

Book design by Jennifer Ann Daddio

Printed in the United States of America

4 6 8 10 9 7 5

CONTENTS

In all cases, these stories are versions told in our own words of traditional tales. While we have attempted to stay true to the traditions from which these stories originate and to the many different elders who shared these stories with us over the past three decades, these are new tellings. Under sources, we have indicated where some of the written versions of these or similar stories can be found.

JOSEPH AND JAMES BRUCHAC

Legends have always played a major role in Northeast Woodland Native American culture. Through the oral tradition, legends have passed down tribal, regional, and family histories, stressed cultural philosophies, taught lessons, and amused Native audiences for thousands of years.

Having survived into the twentieth century, Native legends are now shared with Native and non-Native audiences alike. Aided by their positive ecological and social content, legends from all over Turtle Island are not only told in front of countless audiences but also appear in numerous anthologies, picture books, and novels. In this vast body of legends, however, one type of traditional tale has often been neglected, or at least misunderstood: the monster story. As long as our tales have been told, stories of monsters have played an important role.

During our childhood in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains, my brother Jesse and I were lucky enough to have grown up hearing many Native legends. Having a storyteller as a father, on long winter nights we heard many a tale. Our favorite ones were always the monster stories. We often went to sleep on those winter nights with thoughts of Chenoos, Flying Heads, Cannibal Ogres, and Stone Giants dancing through our heads. Luckily, in most cases we took comfort in knowing these monsters were usually defeated by a brave human being sometimes a child no older than we were then.

Indeed, in many of our traditional Native American monster legends, heroes and heroines defeat their terrible foes by using their wits and standing up against their own fears. This is well illustrated in the stories found in this book, such as the "The Flying Head" and "The Stone Giant." The point of such stories is usually quite obvious. Clear thinking and bravery can be victorious over evil and the twisted mind.

So important was the theme of defeating monsters that it even appears in many Northeast Woodland creation stories. For example, in an Abenaki tale Gluskabe first shaped the human beings out of stone. But those giant rock creatures caused great destruction. Having hearts of stone, they had no compassion for the earth and its many living creatures. After realizing his mistake, Gluskabe destroyed them, turning them back into broken stones. Only after their defeat could he make the first Abenaki people from the ash tree. These new people, unlike the stone beings, had hearts that were green and growing, allowing them to have respect for the earth and each other.

In such legends, be they creation stories or not, the monsters are almost always defeated. This, however, is not always the case in another type of monster story found in this book. That type is the cautionary monster story. Those unfamiliar with such tales could be in for a big shock. In these stories, the monsters often win. Their prey, more often than not, is young children. At times, these stories seem more to resemble an episode of Taled from theCrypt than what many have come to expect from Native American legends. Stories about creatures such as Toad Woman, who lures young children into the cedar bogs with her beautiful voice only to drown them, don't have what most would consider happy endings. Yet this type of monster tale taught the caution that, over the centuries, probably saved thousands of young lives. Despite the many romantic ideas about our northeastern wilderness, it was and continues to be riddled with danger. Indeed, in precontact times one of the leading causes of death for Native people was accidents. These accidents included drowning, falls from high places, animal attacks, and many other things that were especially dangerous for children. Tales of Toad Woman would help frighten children away from the places where potential accidents might happen such as the marshy cedar bogs. Monsters prove to be a more effective deterrent than a parent's simple warning.

To this day on the Abenaki reserve of Odanak, stories also included in this collection are still told about the dangerous little people known as the Spreaders. These Spreaders, as the story is told to the children of the village, are said to live near a certain cliff, a cliff that in reality is a very dangerous place. Whether it be Toad Woman, Spreaders, Stone Giants, Flying Heads, or any other monsters, the images of these creatures continue, in many Native communities, to keep children away from danger.

A second use for the cautionary monster story is to warn against bad behavior. Such bad behavior may result in a monster paying a visit. "Ugly Face" and "Big Tree People" might be used by a parent or other elder when a child is acting in a disrespectful way. In the story of the Man Bear, the hero succeeds because he remembers the advice of his elders. In the tale of Keewahkwee, the rude monster fails where the polite little boy succeeds. Among Native Americans, telling a lesson story or a cautionary tale, instead of resorting to physical punishment, has always been the preferred way to discipline a child. The aim of this type of cautionary monster story is also to help an individual child recognize bad behavior before they commit it.

we Bock

we Bock