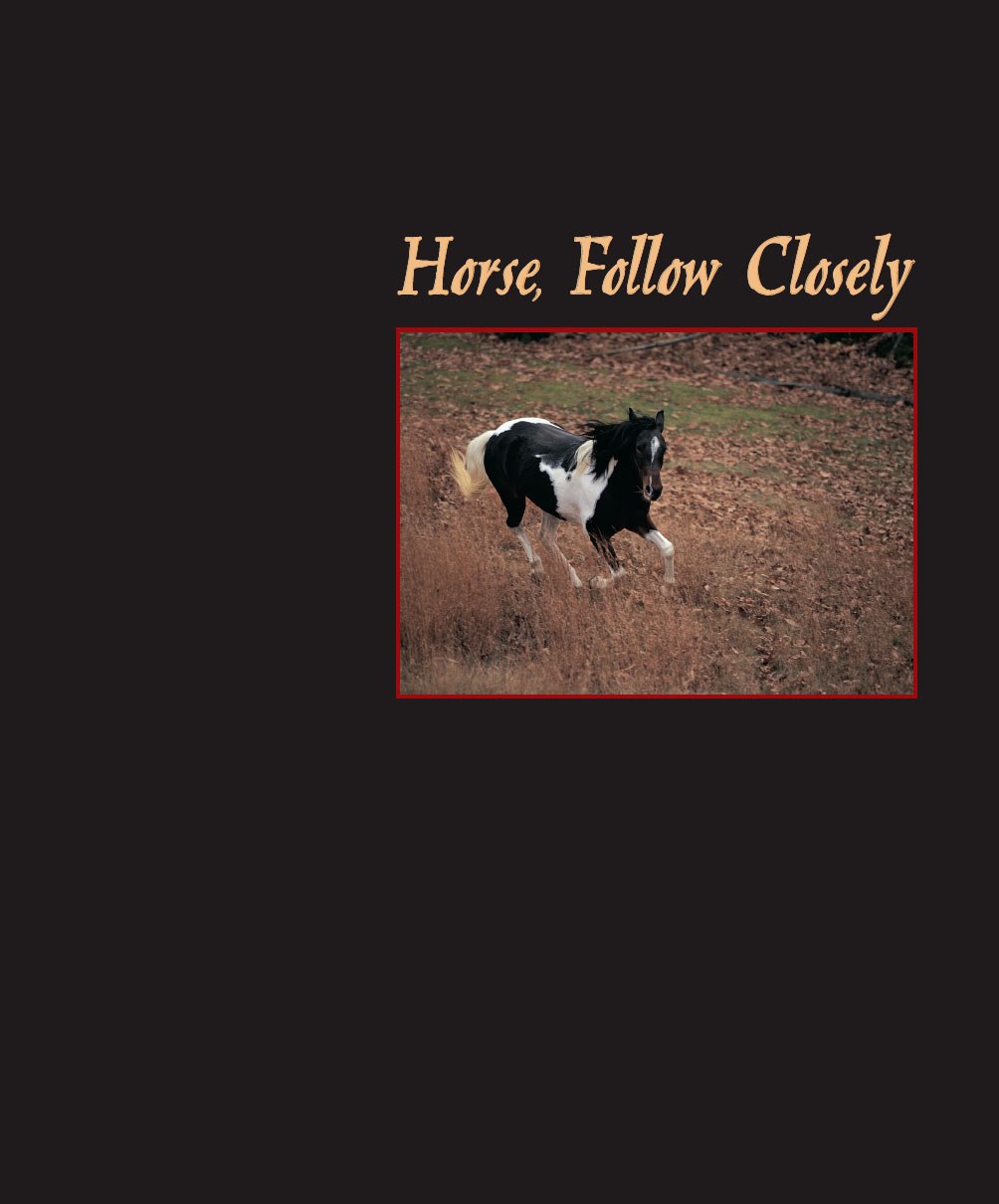

Cover and book design copyright 1998 by Michele Lanci-Altomare

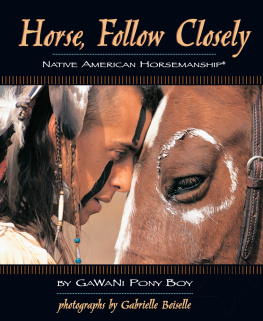

Illustrations by GaWaNi Pony Boy

Text copyright 1998 by I-5 Press

Photographs copyright by Gabrielle Boiselle

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 Press, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

The Native American quotes on pages 26-27, 42-43, 127, 130-131 are reprinted with permission of Council Oak Books from A Cherokee Feast of Days, by Joyce Sequichie Hifler; copyright 1992 by Joyce Sequichie Hifler.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pony Boy, GaWaNi, 1965

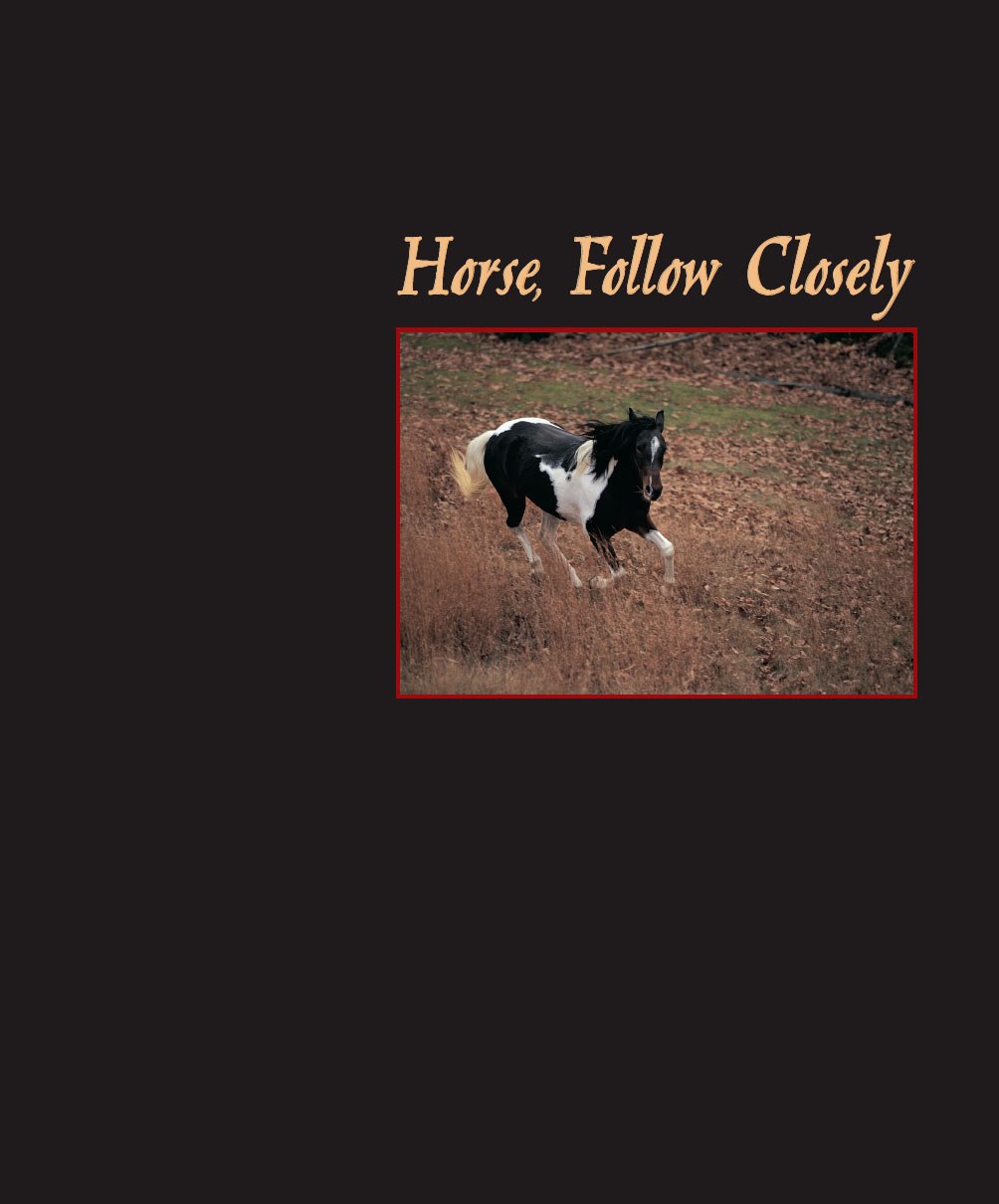

Horse, follow closely / GaWaNi Pony Boy ; photographs by Gabrielle Boiselle.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-889540-22-6

1. Indians of North AmericaDomestic animals. 2. HorsemanshipUnited States. 3. HorsesTrainingUnited States. 4. HorsesUnited StatesFolklore. I. Title.

E98.D67P66 1998

636.1'0835'08997dc21

97-38660

CIP

Paperback ISBN: 978-1931993-89-0

eISBN: 978-1620080-20-7

I-5 Press

A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC

3 Burroughs

Irvine, California 92618

Printed and bound in China

14 13 12 11 6 7 8 9 10

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book is dedicated to Blaise and Riana and made possible by Creator.

GaWaNi Pony Boy

To my grandfather, a patient man who was well known for his ability

to talk with horses; and my father, a talented photographer.

Gabrielle Boiselle

Thanks to Babbit Ranches; CO Bar Ranch; Frank and Maxie Davies of Flying Heart Barn, Flagstaff, Arizona; the Howell family; K & K at Rocking Horse Stables; the Long family; the Trexler Lehigh County Game Preserve; and C & A at THE FARM. Special thanks to Ruth and Lisa, Sharon and Amy, the Assemblies Group, Inc.; and a special thank you to Gabrielle Boiselle, whose creative vision lends life to the images contained herein.

GaWaNi Pony Boy

The time I spent with GaWaNi was very special. We could communicate with almost no words; we felt the heartbeat of nature together and enjoyed every moment of the photo shoot. Thank you GaWaNi for this experience. I would also like to extend my thanks to Andrea Morrell.

Gabrielle Boiselle

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

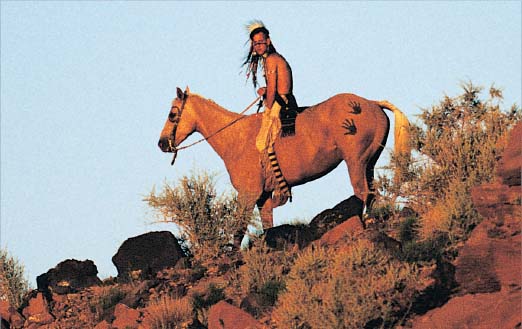

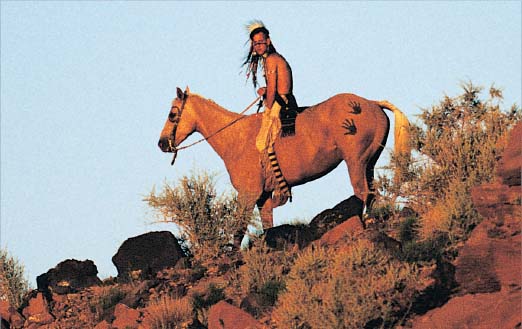

This is the Native American horseman. For many, he represents the ultimate rider. The essence of a horseman, both his skill and intuition, goes beyond the hours he spends in the saddle.

If we are to understand our relationship with the horse, we must first understand the relationship we have with the entire animal kingdom. The human species, directly or indirectly, affects all other species on the planet, even those species we dont directly come in contact with. Every one of our actions affects all living things, and therein lies our responsibility to the natural world. Native Americans understood this. They held at their core the belief that all species are related. They also understood that a certain level of awareness must take place before we can truly communicate with that which is all around us.

It is not surprising, therefore, that in the folklore of every Native tribe are stories, tales, and beliefs to exemplify humans relationship to other animals. Native Americans lived with animals and within their environments. Animals were companions, adversaries, guides, advisors, and role models.

To most tribes, animals were great teachers, and the tribes elders were their pupils. By careful observation and following their example, medicine people learned from the animals which plants were edible and which were poisonous. The animals provided insights about the seasons and migrations and wisdom about natural things.

Native Americans believed that animals regularly communicate with each other and sometimes with human beings. Many of the great medicine people of the past claimed to have spoken with one species of animal or another. Decisions affecting the whole tribe, such as those surrounding migrations, were often based on a message sent by a particular animal to an elder or spiritual leader. In fact, indigenous peoples around the globe have for centuries made decisions and based their lives on messages received from nature and the animal kingdom.

It is only now, in our technologically advanced culturea culture in which we tend to believe only what we can see, prove, and explainthat we view animal-human communication as impossible or ludicrous. Yet the Dr. Dolittle philosophy is not so far-fetched. Many riders experience the apparent phenomenon of their horses doing exactly what the riders are thinking, seemingly at the same time they are thinking it, with no physical or verbal commands. These countless horse owners are not gurus, powerful medicine people, or psychics. They simply understand the relationship they have with their horses. The relationship between humans and other animals can be seen in many Native American stories and legends, which usually place emphasis on what can be learned from animals.

Few traditional legends contain references to the horse because Native contact with the horse was limited to only a few hundred years. When horses were first encountered, some tribes, thinking horses immortal, feared them. Many tribes viewed horses as big dogs. A few did not realize at first that horse and rider were two separate beings. Some tribes ate horses while others immediately saw in the horse a more efficient way of hunting. In light of all this, the Native Americans ability and accomplishment with horses is even more remarkable.

How did horses come to live with Native Americans? Lets look at how horses first came to North America.

Native American Meets Horse

Horses existed in the Americas nearly forty million years ago, long before humans made their appearance. Over the millennia, Equus caballus, the ancient ancestor of the modern horse, migrated to Asia across the Bering land bridge that connected North America to Siberia. There Equus caballus continued to develop within its changing environment. Periodically, glacial melting submerged the Bering land bridge and all migration of mammals across its frozen terrain ceased. Sometime between 600,000 and 1,500,000 years ago, while the waters of the Bering Sea solidified into giant sheets of inland ice, the modern horse migrated back again from Asia to North America.

Then at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, about 10,000 years ago, the horse, along with many other species of mammals, mysteriously disappeared. The exact cause of this mass extinction is not known. What is known is from that time until about the middle of the sixteenth century there were no horses in North America.

In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, waves of Spanish conquistadors arrived on the North American continent bringing horses with them. Christopher Columbus, Ponce de Leon, Vasquez de Ayllon, Panifilo de Narvarez, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, Antonio de Mendoza, Hernandez De Soto all had horses on their explorations. In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, twenty-nine-year-old governor of the most northern province of Mexico, led a contingent of 250 cavalrymen, 2,500 Nahuatl Atzecs and Africans, 500 pack animals, and 1,000 horsesmostly geldings, not stallionsnorthward into the American southwest, land of the Zunis.

Next page