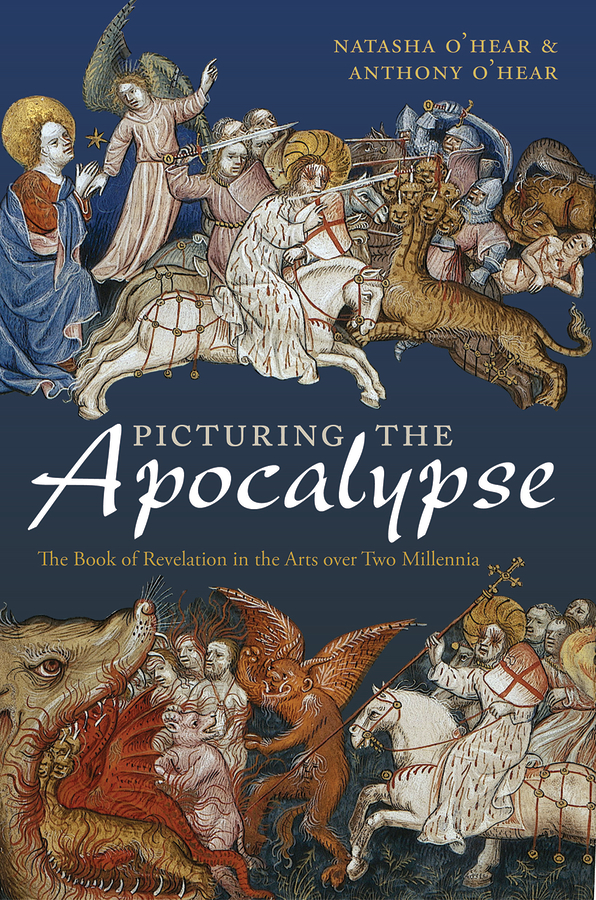

Picturing the Apocalypse

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Natasha OHear and Anthony OHear 2015

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014956593

ISBN 9780199689019

ebook ISBN 9780191002960

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work

For Zac and Freddie, the next generation

Acknowledgements

Picturing the Apocalypse has as its starting point the work done by one of us in Contrasting Images of the Book of Revelation in Late Medieval and Early Modern Art (Oxford University Press, 2011). To that extent the debts of thanks and gratitude offered there spill over into this book too.

However this is a completely new book, different in scope and approach, and written by two authors rather than one, both of whom have played a full part in the writing of the whole. So for Picturing the Apocalypse, we would like to thank David Reynolds for his help with presenting and developing the original idea. Then, apart from the many authorities on Revelation we have drawn on (and some of whom one of us has been taught by), we would like to single out Ian Boxall for his responses to particular questions of interpretation we have had at various points. Particular thanks are also due to Chris Rowland and Sue Gillingham who both read and commented on earlier drafts of the book and remained supportive throughout. Three anonymous readers for the Oxford University Press also gave us invaluable help on matters of content, style and approach. Lizzie Robottom at Oxford University Press commissioned the book and was our original editor, after which she was ably succeeded by Karen Raith, Aimee Wright, and Caroline Hawley.

Daria Pezzoli-Olgiati gave us some very helpful advice on contemporary apocalyptic culture, particularly films. Bryan Appleyard and Alex Pumfrey also helped us with references to contemporary culture, while Ian McEwan and Roger Scruton greatly helped us in refining our attitude to Revelation by getting us to face up to, and in part to respond to, its dark side. Ruth Padels interest and quiet encouragement during this time of struggle, so to speak, was invaluable, as was David Matthews, who also introduced us to Vaughan Williams Sancta Civitas. Phillida Gili alerted us to the breadth of the Spanish Beatus Apocalypse tradition. At a very late stage we were fortunate enough to speak to James MacMillan about his musical journeys in Revelation. Working with the artist Michael Takeo-Magruder on his exhibition De/Coding the Apocalypse brought a new dimension to our thinking.

There are 120 illustrations in the text, and we have received help from many individuals and institutions in sourcing these and obtaining permissions. To all who have helped here, we would like to record our gratitude. We cannot list everyone here, but for particular help we would like to mention first the artists Gordon Cheung, Kip Gresham, and Siku, who were all most generous in allowing us to reproduce their work. Marie-Jose Friedlander was most helpful in discussing Revelation images from Ethiopia, and in allowing us to reproduce one of her lovely photographs. Nomi Rowe helped us in tracking down the image of Cecil Collins Angel of the Apocalypse, and Clive Hicks, the photographer, sought out his photograph for us. Jonathan Robe helped us with the James Chadderton image, and we would like to thank them both. Cheryl Sukut from Tyndale House Publishers went to a great amount of trouble to supply us with the Left Behind image, while Barbara Bernard from the marvellous National Gallery of Art in Washington went way beyond any call of duty in finding for us a photograph of Max Beckmanns lithograph And God shall wipe away all tears . It was extremely difficult to track down the image we wanted from Frans Masereels Apocalypse series, but, following help from Pauline Bonnard of DACS, Peter Riede, President of the Frans Masereel Stiftung in Saarbrucken came to the rescue just in time. Michael Stone from the Chicano Studies Research Center, UCLA, put us in touch with Yolanda Lopez, while Patrick Rogers from the Rosenbach of the Free Library in Philadelphia was most helpful with Blakes The Number of the Beast is 666, as was Martin Townsend, editor of the Sunday Express, over the Bunbury cartoon. We are also grateful to Michle Brezel of the Muse Virtuel de Protestantisme and to the Chapter of York and York Glaziers Trust for freely supplying images. The Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge were very generous and we would also like to thank John Moelwyn-Hughes for helping us navigate the Bridgeman Art Library.

Finally, we would like to thank our constant readers, critics, and supporters Philippe Bonavero, Patricia OHear, Jacob OHear, and Thea OHear (who also helped with the Index).

Contents

plate 1. The Van Eycks, The Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, Ghent: St Bavo's Cathedral. Bridgeman Art Library

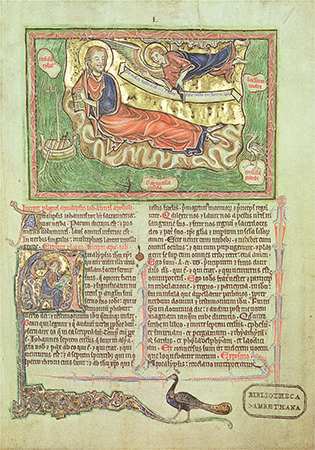

plate 2. The Gulbenkian Apocalypse, c.1270, The Last Judgement (Rev. 20.1115), Lisbon: Museo Calouste Gulbenkian. Museo Calouste Gulbenkian

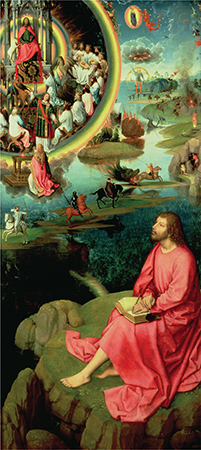

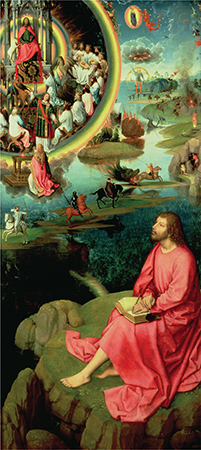

plate 3. Hans Memling, The Apocalypse Panel, detail from the St John Altarpiece, 14749, Bruges: The Memling Museum. Bridgeman Art Library