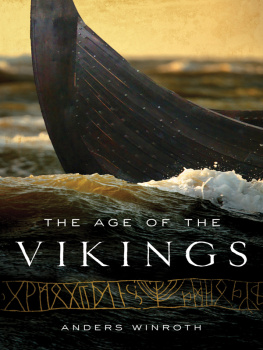

THE AGE OF THE VIKINGS

MAP 1. Europe in the Viking Age. Cartography by Bill Nelson.

MAP 2. Northern Europe in the Viking Age. Cartography by Bill Nelson.

THE AGE OF THE

VIKINGS

ANDERS WINROTH

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William

Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6

Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photograph Kirsten Jensen Helgeland.

Jacket design by Faceout Studio.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Winroth, Anders.

The age of the Vikings / Anders Winroth.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14985-1 (hardback : acid-free paper)

1. Vikings. 2. Civilization, Viking. I. Title.

DL65.W63 2014

948'.022dc23

2014006488

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Verdigris MVB Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

TILL MINA FRLDRAR

THE AGE OF THE VIKINGS

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

The Fury of the Northmen

F INALLY THE CHIEFTAIN TOOK HIS HIGH SEAT. THE WARRIOR band had waited eagerly on the benches around the great hall, warmed by the crackling fire, quaffing bountiful mead. The chieftains servant girls had spent weeks this fall mixing honey and water, brewing barrels full for his famous party at Yule, the old Scandinavian festival of midwinter. Now the chieftain was there in his best clothes demanding to know why his famed warriors had been given such simple drink. Did they not deserve better hospitality after all they had accomplished in Frankland? Had they not hauled home barrels of the best Frankish wine from the rich cellar of that monastery last summer and paid dearly for their loot with their blood?

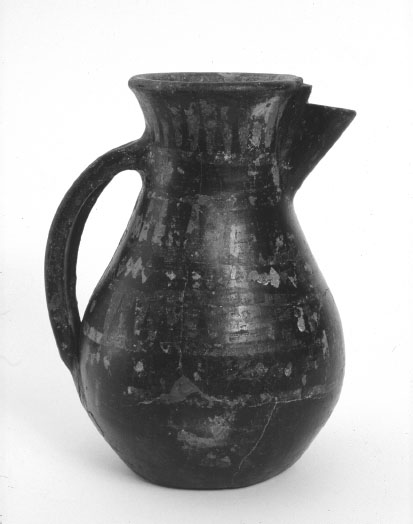

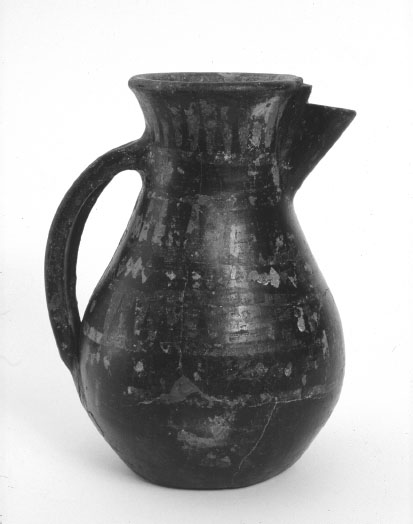

The appearance of the pitcher, its perfect regularity so unlike the clumsy local earthenware containers that most of them were used to, hushed the rowdy warriors in the vast hall. Tin foil in several horizontal lines and, between them, sequences of rhombuses decorated the pitcher, a glorious vessel for an exotic drink. The chieftain, served first, received a chalice with an artful decoration of blue glass in delicate strands after which the man in the seat of honor was handed a matching glass. The rest of them drank out of horns or simple mugs, but now everyone drank wine instead of mead to celebrate their bravery and their success when they had gone on Viking raids during the summer. Some of the warriors, recognizing the glassware bought by the chieftain when the band of warriors had visited the town of Hedeby on the way home from raiding, whispered that the blue-shimmering glasses were from a faraway kingdom called Egypt; the chieftain could have procured a good longship for what he had paid for them after hard negotiation.

FIG. 1. This beautiful pitcher made on a fast-spinning potters wheel was manufactured inside the Frankish Empire but found in a grave in Birka, Sweden. The pattern was made by attaching thin tin foil. Photo: Gunnel Jansson, courtesy of Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.

Used to coarser drink, some of the warriors were unfamiliar with the taste of wine. What a great leader of men who so generously shared such luxuries! And he looked the part, too. His cape featured embroidered leopards and silver sequins, and it was trimmed with lustrous fox fur. He sported a silk cap on his head. An eiderdown pillow with a beautifully embroidered cover depicting a procession of people, horses, and wagons cushioned his seat, and by his side stood a ceremonial ax with rich decoration in silver-wire inlay depicting a fantastic animal. This was a real chieftain! Where did he get all these amazing things? Few of the warriors had ever been this close to such luxuries. They had never seen foxes as darkly glistening as these, nor had they experienced any textile that could shine this luminously.

Not everyone in the hall had sailed out last summer with this chieftain to seize opportunities in Frankland; many newcomers had come to the chieftains celebration. They could be heard bragging about how they, next summer, would go with this chieftain to redden their swords with the blood of the Franks and the English, or why not the Moors in Spain? And they were going to gain undreamed-of riches.

This past summer, they had not been so fortunate. Of the three ships that had gone out under another chieftain, only one came back, and that was without their leader, who had fallen, it was rumored, when the Frisians had unexpectedly fought back. Nobody was really sure what had happened, for those who had returned were not eager to talk about it.

It was time for the food to be brought in, but first the gods must have their share. The chieftain cut the throat of the sacrificial animal and let the blood stream down on the floor, pouring some wine on top of it. The chieftain also held up a tiny gold foil between his fingers for everyone to admire. Those who sat closest could just make out an embossed picture of a couple embracing. The chieftain attached the foil to one of the posts supporting the roof. Not all of his warriors were sure exactly what this ritual implied, but they were certain it must be beneficial. The sacrificed lamb was taken out to be roasted, and the rest of the food was brought in, large chunks of roasted meat, cauldrons of boiled fish, and sweetmeats. The warriors feasted heartily and happily on all that was on offer. One certainly did not need to bring any packed food to the feasts of this illustrious chieftain!

Their bellies full of a glorious meal, everyone was leisurely cracking the hard shells of nuts to get to their sweet contents as dessert, but the chieftain himself and his closest men were having larger nuts that were easier to open, for their shells were softer and thinner. Were their contents more delicious, too? Few in the hall had ever tasted these foreign welsh nuts, or walnuts. Some of them remembered seeing a single walnut when it had been put in the magnificent grave of the last great chieftain before this one.

That funeral had been something to behold: the dead man was given a huge, gorgeous ship with exquisite wood carvings, which was going to ferry him to the Afterworld. People were impressed that his son was willing to sacrifice such a grand vessel, although malicious tongues whispered that the ship was anyway not very seaworthy and had capsized twice, drowning the chieftains brother. The son of the old chieftain had also sacrificed an unheard-of number of horses on the foreship. People talked at length of the sea of blood on the deck of the funeral boat before soil was thrown over the boat to form a mound, from which, as a reminder, the mast still protruded.

The skald stood up in the middle of the hall, and the warriors, by now boisterous, did not quite fall silent, but the hall became still enough that most people could hear him. He turned to the chieftain and declaimed: Listen to my poesy, destroyer of the dark blue, I know how to compose. This skald was a good one, even a very good one; one could hear from his accent that he was an Icelander as, everyone knew, were all the best skalds. The warriors enjoyed the euphony of the verses he recited: the rhythm, the alliteration, the end rhyme, the slant rhyme, the assonances, but they did not quite understand every stanza. So unnatural was the word order, so complex the waft of rhyme, and so far-fetched the poetic circumlocutions. Dark blue what exactly? Wound-swans? Meals of giants? But the verses clearly celebrated the achievements of last summers Viking adventure. The warriors recognized individual words: Franks, fire, gold, horses, a raven. A warrior suddenly burst out, We fed the raven well in Frankland! when he suddenly realized that this was the solution to part of the riddle of one stanza. Everyone cheered, and the poet had to fall silent for a moment. In the ancient poetry of the Norse, to feed the raven (also poetically known as the wound-swan) meant to kill the enemy, providing a meal for beasts that feed on carrion. It was difficult for the drunken warriors to make out even such phrases, for the Icelander excelled not only in far-fetched expressions, but also in using unnatural word order and rare locutions. The beginning line had been easy enough, for the skald began, strategically, with expressions readily understandable. There could be no doubt, either, of the ending, for his gestures and inflections made it abundantly clear when he reached the grand peroration of his praise of the chieftain.

Next page