Carol Devine & Wendy Trusler

The first thing that comes to mind about Antarctica is not likely food. But if you are going to spend any time there, it should be the second.

In 1996, we led several volunteer groups to Bellingshausen, a Russian research station in Antarctica, for an environmental project organized in collaboration with the Russian Antarctic Expedition. A total of fifty-four people from five countries paid to pick up twenty-eight years of garbage during their holiday on a continent uniquely devoted to peace and science.

The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning is a journey through that austral summerthe story of a Russian-Canadian cleanup project on a small island 120 kilometres off the Antarctic Coast (6202's 5821'w). It is also a look at the challenges of cooking in a makeshift kitchen during the long, white nights at the bottom of the world.

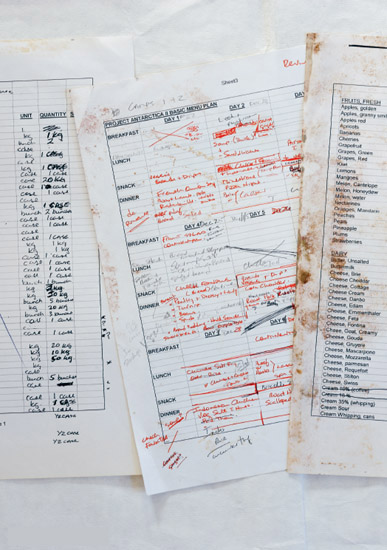

The book unfolds in the style of Antarctic publications such as Sir Ernest Shackeltons handmade Aurora Australisthrough provision lists, menu plans, journals and letters. Woven throughout are historic and contemporary images, food and science notes as well as vignettes from Antarctica.

Early explorers and scientists endured unimaginable conditions, surviving on penguin meat and even dog paw stew. The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning is an ode to them, to contemporary explorers and scientists and to the people we met who captured our hearts.

It has been a curious and beguiling exercise for us to reflect on our experiences in a male-dominated fish bowl.

Whenever adventure beckons an open mind and a full stomach are necessities.

Yet as those noble peaks faded away in the mist, I could scarce express feelings of sadness to leave the land that has rained on us its bounty and been our salvation.

Carol

I always wanted to go to Antarctica without knowing why. I grew up in the subarctic and often went to school with icicles in my hair. I used to press one hand on the top of the globe and with the other spin it so quickly that the water and continents blurred together. What was that odd-shaped white continent down there on the bottom? Ptolemy mapped Antarctica in antiquity before anyone even knew it existed. There was only intuition that a continent must exist at the bottom of the world counterbalancing the land masses at the top. Humans have inhabited Antarctica only in the last 100 years.

Antarctica occupies a tenth of the earths surface. Scientists tell us that the icy continent most resembles the moon of Jupiter: Europaalso thought to hold a liquid ocean beneath its ice. None of us are going to Europa, and only a tiny sliver of the human population will ever be lucky enough to visit Antarctica. I was one of the fortunate few. My first moments on the continent felt as if I had reached both the moon and a kind of paradise amidst those baby blue icebergs. It was a place where each footprint felt momentous and each interaction vividly important.

Antarctica holds the majority of the worlds ice and fresh waterit is critically important to the planet and is a mirror reflecting what we humans mean for the Earth. Natures laboratory in the south reveals things like a record of the earth's climate held in its 420,000-year-old ice core. What happens in Antarctica doesnt stay in Antarctica and vice versa. The Antarctic Peninsula and the surrounding oceans have warmed faster than anywhere else in the Southern Hemisphere. It is evident, in the first moments one spends here, that the continent bears devastating marks of human activity.

As a nascent humanitarian, I wanted to do something previously untriedto set up a project that would give Antarctic visitors an opportunity to help conserve the environment in that wild, remote place.

I approached Sam Blyth who ran a company that took adventurers to the Antarctic and together we created the VIEW FoundationVolunteer International Environmental Work. Pat Shaw, Vice-President of the polar travel side of Sams company, Marine Expeditions International (MEI), suggested a VIEW project in Antarctica and helped lay the groundwork.

For starters, we needed a partner in Antarctica. I wrote letters to the appropriate authorities in the U.K., Russia, Poland and Australia asking if they would be interested in having international volunteers assist with conservation efforts at their Antarctic stations.

On June 16, 1994, I received a handwritten letter from the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. At the Henryk Arctowski station in the South Shetland Islands, the scientists were already starting to consolidate debris that had accumulated at its base since opening in 1977. This first collaborative environmental initiative would become Project Antarctica.

MEN WANTED

for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.

Ernest Shackleton 4 Burlington st.

Fabled ad in London newspaper circa 1914 for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 19141916

TRAVEL ADVISORY: ANTARCTICA; SOUTH POLE CLEANUP

The New York Times Archives

January 29, 1995

Sightseeing is, of course, allowed, but travelers who sign on for a 12-day trip to Antarctica will spend much of their time cleaning up a research station.

Organized by VIEW, a Canadian conservation group, the trip, from March 10 to 21, entails four days of not-too-hard labor, like putting light debris into garbage bags, at the Polish Research Station.

From Buenos Aires, travelers fly to Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, then board the Akademik Sergey Vavilov, a 79-passenger Russian research vessel, for Antarctica.

The trip$1,800 a person plus $1,102 round-trip air fare from New York to Buenos Airesincludes lectures and a cocktail party. Information: (416) 964-1914.

Next we needed volunteers able and willing to pick up garbage and cover their own travel expenses. I faxed a press release to major newspapersThe New York Times, The Toronto Sun, The Boston Globe