For Bruce and our children, Lily and Jack

CONTENTS

Introduction

MY GRANDMOTHERS FRONTAL LOBES

Frontal lobe n. (pl. frontal lobes) 1. Each of the paired lobes of the brain lying immediately behind the forehead, including areas concerned with behaviour, learning, personality and voluntary movement. A region of the brain that influences higher mental functions often associated with intelligence, such as the ability to foresee the consequences of actions, planning, comprehension and mood.

I first became fascinated by the frontal lobes of the human brain when I saw my grandmothers sprayed across the skirting board of her dark and cluttered house. I was fifteen.

A young woman eight months pregnant, I discovered much later, and a heroin addict had battered her about the head with an iron fire poker. She was an ex-tenant of my grandmothers. This woman knew that her former landlady, a German Jewish refugee recently converted to Christianity, had treasures and cash galore stashed among the chaos of her large house, the top two floors of which she rented out.

A few blows to the head, a quick rifle through purses and drawers, and the woman was off, cash in her pocket to pay off her dealer and secure her next hit. My grandmother lay on the carpet of her front room, bleeding from a large head wound. I dont know whether she was conscious or not. I do know exactly how she died: by slowly asphyxiating, choking to death on her own blood.

Asphyxiation: that was the problem, of course. If only shed died instantly from the head trauma, the crime would have been treated as murder. If only she hadnt been a stubborn, wilful woman a woman who had fled Nazi Germany pregnant with my father, a woman who had lost many of her family in concentration camps, a woman who never took anything lying down, except when she was beaten with an iron fire poker.

There she lay, refusing to die, until she choked on her blood. The woman who had beaten her was sentenced to only three years for manslaughter with diminished responsibility. She had her baby in prison and was out within eighteen months.

OK, to be honest, I am not entirely sure that my grandmothers brains were on the skirting board when I went into her house that day at the age of fifteen. Is that a direct memory or something I told myself later on? In fact, Im not sure I remember much of that day at all except two things: a massive bloodstain on the carpet and my father making a noise like an animal caught in a trap.

In that moment I became the rational coper. My darling father howled, but I just shut down and began to try and understand how and why.

Had she died in pain? Did she know she was dying before she died? What had compelled her murderer to smash her head in? Had the woman planned it? Did she want to kill my grandmother or merely maim her so she could plunder?

All these questions about the shit end of life, at a time when I should have been unthinkingly hedonistic. At fifteen years old, my frontal lobes were in a post-pubertal stage of reorganization, which meant I should have been taking my own risks and thinking bugger all about the consequences.

But on that March morning it was only and all about frontal lobes: my grandmothers on the skirting board (perhaps), her murderers clearly under-functioning and mine, clicking into a precocious place of calm rationality that I now believe began my journey into the profession of a mental health practitioner.

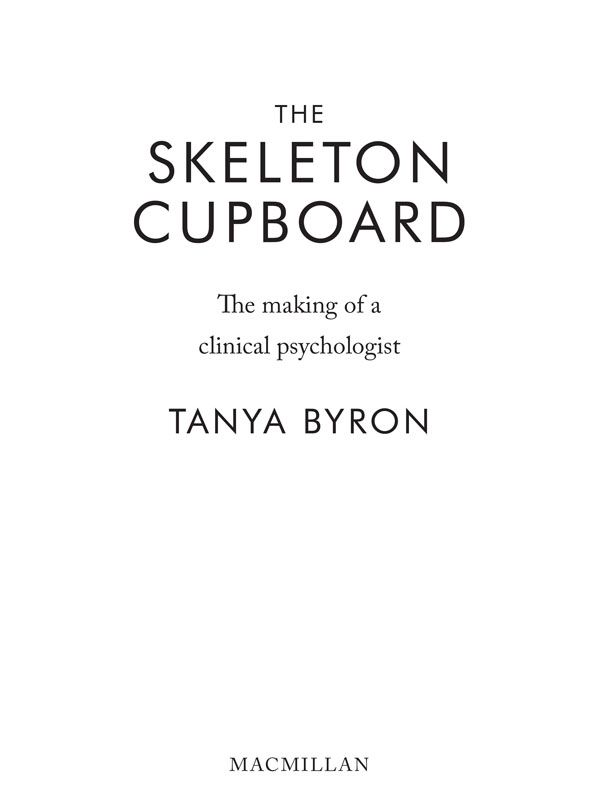

This book tells the story of my clinical training. It takes place over the course of three years from 1989 to 1992, when I was in my early twenties, during which I underwent a series of placements in different mental health settings and worked with several distinct kinds of patient: troubled children; families in crisis; men and women dealing with the encroaching effects of dementia; those struggling with drug dependency, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction and terminal illness and, in one case, a sociopath.

After completing my BSc in psychology at the University of York, in the north of England, I had moved back to live in a flat in London, the city in which I grew up. My childhood had been busy, creative and exciting. My father was a successful TV, film and theatre director a brilliant, highly emotional, inspiring man. My mother was a senior nursing theatre sister and occasional model. My sister, Katrina, only fifteen months younger than me, and I grew up surrounded by art and culture which I loved and went to a highly academic all-girls school which I hated. Life was full of interesting people coming through our house; dinner conversations were always lively and passionate; my mother was a calm, steady presence in the busy, sometimes manic world of the creative people who worked with my father.

I never intended to be a mental health practitioner; I wanted to work in film and TV, making documentaries about social issues. Quite unexpectedly, I managed to get onto a postgraduate clinical training course and decided that a further three years would allow me to make authentic films and TV programmes about mental illness. I wanted to demystify and destigmatize it.

Almost twenty-five years on, I still practise clinically alongside writing, journalism, broadcasting and policy advising. Best of all, I am the mother of two fantastic teenagers, Lily and Jack.

Although I have written books about child development and parenting, I have never felt able, until now, to write more fully about the experiences of working in mental health. Its taken this long to distil the experience of working with some of the most amazing people I have ever known people who trusted me enough to tell me about their lives.

I am going to start at the beginning and tell the stories of my training as a well-meaning but inexperienced young woman. I had to learn on the job: half the week at University College London, receiving lectures and training in models and approaches in mental health, writing essays, case reports, a dissertation and taking exams; the other half of the week on a series of six-month placements, attempting, with regular supervision, to apply this learning.

The training took place within the National Health Service, and I spent time in hospitals, clinics, mental health units and GP surgeries. I saw patients referred to me by many different specialists in health and mental health people struggling with acute, chronic and at times profoundly debilitating mental health difficulties. Some were mildly impaired, others dealing with long-standing difficulties. Occasionally there were patients who presented such a degree of risk to themselves or others that they had been sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Over three years I was given six six-month placements, structured to provide a complete training experience across the age span and full spectrum of mental health issues by the time I qualified.

There is no other way to narrate the training of a clinical psychologist than to tell the stories of those I encountered, so the book is inspired by the cases I worked and my experiences treating people as a new and naive mental health practitioner. However, because confidentiality is a core principle of my profession, while all I describe is drawn from real clinical practice, the characters I write about are not modelled on real individuals. They are constructs, influenced by the many incredible people I had the privilege of meeting during my training.

I dedicate this book to them.

Tanya Byron

London, April 2014

One

THE EYES HAVE IT

Next page