THE DISCOURSE OF RACE IN MODERN CHINA

FRANK DIKTTER

The Discourse of Race in Modern China

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Copyright Frank Diktter 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title

Diktter, Frank.

The Discourse of Race in Modern China

ISBN 9780190231132

eISBN 9780190613334

CONTENTS

Races do not exist, they are imagined. So I wrote in the preface of The Discourse of Race in Modern China more than twenty years ago. This always seemed to me to be a rather uncontroversial argument, all the more since the concept of race had been repeatedly exposed as a dangerous illusion by a broad range of historians, sociologists, anthropologists and biologistsone thinks of Richard Lewontin and Stephen Gould. But I underestimated the tenacity of racial discourse. As Marek Kohn underlined in his Race Gallery: The Return of Racial Science, scientific arguments in favour of race are persistent and versatile.

The very fact that science itself is a complex and ever-evolving field speaking in many voices means that new claims purporting to demonstrate the existence of racial differences continue to reappear. Recent advances in genomics, for instance the Human Genome Project, have even led to folk notions of race being given renewed credibility today. Not only do some biologists claim that the five races historically envisaged by Blumenbach and others several centuries ago really do exist, but it is also alleged that black, brown, red, yellow and white people have significant differences at the genomic level that lead to their susceptibility to particular diseases.

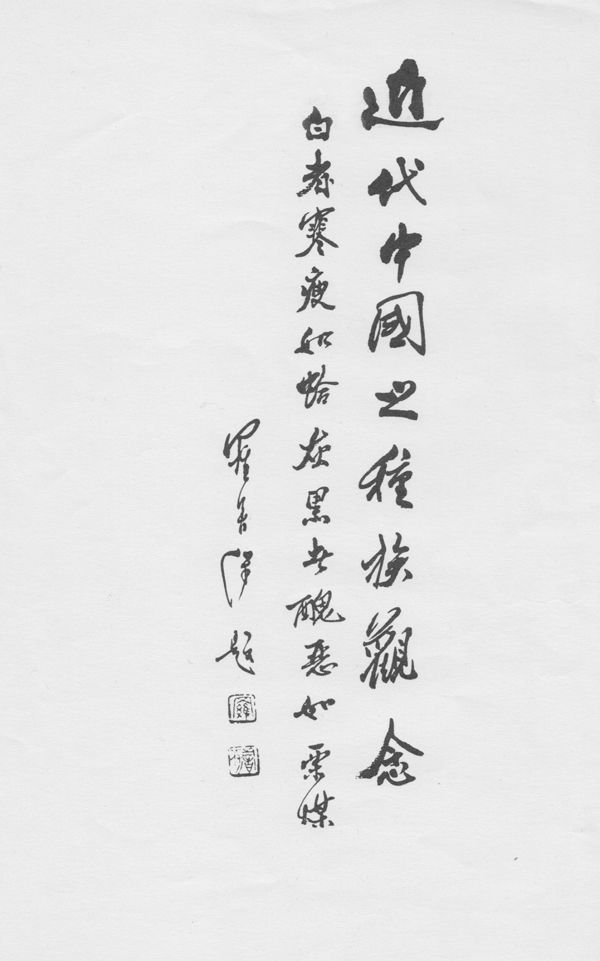

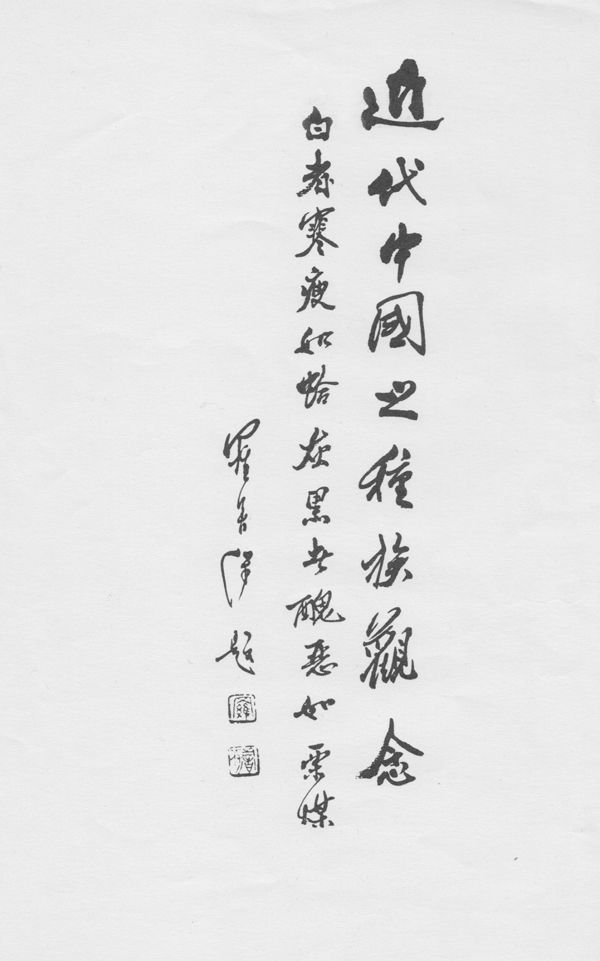

As the new chapter at the end of this revised edition shows, similar claims are common in the Peoples Republic of China. The injunction from Yang Lien-sheng, with which the book concluded twenty years ago, is as relevant now as it was then: racial discourse should be spelled out in order to be dispelled, all the more as it has widespread currency in the worlds second largest economy.

Another trend since the publication of The Discourse of Race in Modern China belongs to a tradition sometimes referred to as the cognitive and evolutionary approach. Its proponents agree that racial classifications have no biological foundation, but believe that race is more than just a social construct: it is a basic cognitive category common to all societies, ancient and modern. Race, from their point of view, is not culturally and historically contingent. Racial categorisations might well be elaborated in slightly different ways, but, in the words of Edouard Machery, humans tend to classify people when they meet other people with different phenotypes.

This is probably the most misunderstood aspect of my book, and I would like to briefly address it here. As the title indicates rather unambiguously, the book is about modern China. Like most social constructivists, I argued that the concept of race is a recent, modern invention heavily dependent on the rise of science. There were no white or black people anywhere until racial theories appeared first in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and then elsewhere. The first chapter in the Discourse of Race looks at the premodern era. The title of the chapter is clear: Race as Culture. It points out that the very distinction between race and culture is a modern invention which has no validity for the premodern era. In the case of China, what some would today term as race overlapped with culture. The chapter gives several examples. In a twelfth-century description of African slaves, bought from Arab merchants by rich merchants in Canton, cultural change was believed to entail a physical transformation:

Their color is black as ink, their lips are red and their teeth white, their hair is curly and yellow. There are males and females They live in the mountains (or islands) beyond the seas. They eat raw things. If, in captivity, they are fed on cooked food, after several days they get diarrhoea. This is called changing the bowels [huanchang]. For this reason they sometimes fall ill and die; if they do not die one can keep them, and after having been kept a long time they begin to understand human speech [i.e. Chinese], although they themselves cannot speak it.

In popular Daoism, a human had to change bones [huangu] in order to become immortal: by analogy, African slaves were expected to change bowels [huanchang] to become half-human. A physical transformation, in other words, was perceived to be an intrinsic part of cultural assimilation. Even in the nineteenth century, scholar-officials like Xu Jiyu who had extended contact with European traders and were familiar with world geography wrote how the hair and eyes of some [Europeans] gradually turn black when they come to China and stay for a long time. The features of such men and women half-resemble the Chinese.

But to say that race is a modern construct dependent on the language of science does not mean that it appeared out of nowhere. It is precisely because it is a historically contingent concept that it is important to look at the pre-existing moral and cultural traditions which have assisted, or on the contrary prevented, the appearance of racial thinking in China. This was the second purpose of the first chapter. It showed that while the concept of race did not appear until the end of the nineteenth century, there were many cultural, social and political traditions that had a strong resonance with the racial categorisations that would spread like wildfire after 1895. These are, among others, the symbolic importance given to the colour yellow, a negative view of dark skin and a patrilineal way of organising society which strongly emphasised lines of descent. Put differently, the book argued that racial discourse in modern China was not simply translated from Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, but was the result of a complex process of negotiation and appropriation, as racial thinkers constructed a new worldview with very complex cognitive, social and political dimensions. In brief,

Next page