Vintage Books Edition, October 1988

Copyright1974 by Jonathan D. Spence

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., in 1974.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

Ching Sheng-tsu, Emperor of China, 16541722.

Emperor of China; self-portrait of Kang-hsi.

1. Ching Sheng-tsu, Emperor of China, 16541722.

I. Spence, Jonathan D. II. Title.

[DS754.4.C53A33 1974b] 951.030924 [B]

eISBN: 978-0-307-82306-9

74-17106

Portions from The I Ching: or Book of Changes, translated by Richard Wilhelm, rendered into English by Cary F. Baynes, Bollingen Series XIX, copyright1950 and 1967 by Bollingen Foundation, reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

v3.1

This book is dedicated to

ARTHUR FREDERICK WRIGHT

and to the memory of

MARY CLABAUGH WRIGHT

Contents

Acknowledgments

I AM especially grateful to three people for their aid and encouragement: Professor Arthur Wright, who listened patiently as I thought aloud the many variants of this book over the years, and gave valuable advice on the final drafts; Andrew C. K. Hsieh, whose ingenuity and enthusiasm as a research assistant helped to give the book the scope I had hoped for; and Jan Cochran, who transposed my convoluted longhand drafts into typescript with skill and good humor.

Many other colleagues, scholars, and students helped me with advice, criticism, translations, and references. My thanks to Beatrice S. Bartlett, Chang Wei, Chuang Chi-fa, Fang Chao-ying, Joseph Fletcher, Parker Huang, Olga Lang, Anthony Marr, Susan Naquin, Jonathan Ocko, Robert Oxnam, Father Francis Rouleau, Nathan Sivin, and John Wills. Silas Hsiu-liang Wu was particularly generous in sharing with me his great knowledge of early Ching texts and institutions; I am also indebted to Charles Chu, who wrote the ideographs that introduce each chapter.

Drafts of this book were discussed at colloquia and seminars held at Columbia, Harvard, Princeton, the University of Vermont in Burlington, and Yale; many of those present at these gatherings gave me useful advice and cautions, for which I thank them. The leisure to think through alternative organizing structures for a study of Kang-hsi, and to undertake the necessary basic research, was provided by the Yale Fellowship in East Asian Studies, to the donor of which I am now indebted for a second time. The final version was written on a Yale triennial leave, and speeded by additional research funds provided by a grant from the Yale Concilium on International and Area Studies.

J ONATHAN D. S PENCE

Timothy Dwight College

Yale University

April 29, 1973

Kang-hsis Reign

T HIS book is an excursion into the imperial world of Kang-hsi, who was Emperor of China from 1661 to 1722. The purpose of the journey is to gauge the dimensions of his mind: What inner resources did he bring to the task of governing China? What did he learn from the world around him, and how did he view his subjects? What gave him joy and what made him angry, how did time pass for him, onto what did his memory fasten? How did a descendant of conquering Manchu warriors adapt to the Chinese intellectual and political environmentand how was he affected by new currents of Western scientific and religious thought that Jesuit missionaries brought to his court?

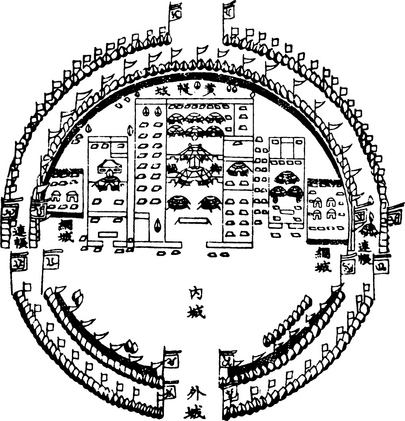

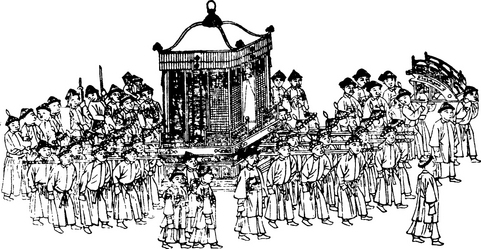

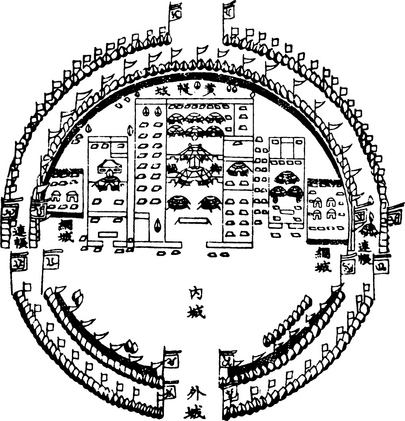

Any attempt to explore the dimensions of the Emperors mindif such an exploration were intended to reveal idiosyncratic and human elementswould have been viewed as both incongruous and presumptuous by Kang-hsis own subjects. Kang-hsi had entered, by inheritance, into a documented sequence of emperors that stretched back for eighteen hundred years, and into a recorded history of China that reached over two millennia behind that. By acceding to office the emperor became more than humanor, conversely, if he revealed human traits, those traits must accord with the accepted historiographical patterns of imperial behavior. In becoming emperor, Kang-hsi became the symbolic center of the known world, the mediator between heaven and earth, in Chinese terms the Son of Heaven, who ruled the central country. Much of his life had to be spent in ritual activity: at court audiences in the Forbidden City, offering prayers at the Temple of Heaven, attending lectures by court scholars on the Confucian Classics, performing sacrifices to his Manchu ancestors in the shamanic shrines. When he was not on his travels, he lived in the magnificent palaces in or near Peking, surrounded by high walls and guarded by tens of thousands of troops. Almost every detail of this life emphasized his uniqueness and superiority to lesser mortals: he alone faced the south, while his ministers faced the north; he alone wrote in red, while they wrote in black; the ideographs of his boyhood personal name (Hsan-yeh) were taboo throughout the empire while the ideographs for Emperor were set apart from and above the lines of text in any document in which they occurred; his robes and hats had designs that no other person might wear; before him all subjects prostrated themselves in the ritual homage of the kowtow; and even the word which he used for I, chen, could be used by no one else.

Such marks of grandeur and recognition were owed to all emperors and, since the emperor was viewed in categories that were cosmic and institutional rather than human, personal sources on emperors of China are rare. Most of them are hopelessly remote from us, hidden behind their various screens. But though Kang-hsi was fully conscious of the inherited weight of imperial tradition, he was also, luckily, a man who expressed his private thoughts with a candor and freshness not normally found in those who govern great empires. To be sure, these personal expressions are scattered and often fragmentary, dispersed in a mass of formal edicts and utterances that were couched in stereotyped language. By searching carefully it is possible, however, to hear the unmistakably authentic voice of a man talking about his attitudes and values in his own words.

Each of the first five parts of this book constitutes one of the categories into which Kang-hsis thoughtsinasmuch as I was able to reconstruct themseemed naturally to fall. Though the categories are not ones historians customarily use to organize their institutional or biographical data, it is true that the varied aspects of Kang-hsis public activities seem to fall naturally within a certain private and emotional framework. My belief that such is the case accounts for the structural organization of the book: by the end of it, the reader should have been introduced to Kang-hsis major concerns in a way that would have made logical sense to the Emperor himself.