Epilogue

by Paul Kramer

THE MANCHURIAN MONARCHY OF HENRY PU YI WAS HELD by no binding force but Japanese military power. Although the dynasty was old, the Emperor, as evidenced by this autobiography, was neither personally imposing nor attractive. Furthermore, the original Manchu majority of Manchukuo had been overwhelmed numerically by a vast influx of Chinese and a minority immigration from both Russia and Japan. None of these newer residents had a motive to make sacrifices for the Crownthe Russians because it was yellow, the Japanese because it was alien, the Chinese (Hans) because it was foreign. It thus crashed, along with the Japanese Army that was its support, a few days after Russias declaration of war on Japan, with no evidence of its being able to enlist popular backing against an invader of another color.

But to suppose that the ease with which Pu Yis Manchu monarchy was overthrown is indicative of its political insignificance is to overlook the condition of the Sino-Soviet frontier. The border between the two countries has never in more recent times coincided with a clear delineation of the peoples who live near it. There are in China roughly two-and-a-half million Manchu people living largely north of the Great Wall and south of the Russian frontier. There are also one-and-a-half million Mongols along the frontier who have been content since the eighteenth century to accept varying forms of Manchu leadership. In addition there are an undetermined number of Manchus within the borders of the Soviet Union since the Siberian territory north of the Amur River and the present Maritime Territory of Siberia were once part of the Manchu inheritance, until detached from China and ceded to Russia in 1858 and 1860.

Outer Mongolia, with a population of roughly a million Mongols and today a Soviet dependency, was under the Ching Dynasty, a Chinese vassal. There are also Mongols living north of the frontier, in the USSR itself. The claim that China under Mao Tse-tung erased the insults in the form of territorial concessions that the imperial powers imposed upon China under the corrupt and feudal Chings is belied by the dependency of Outer Mongolia on the Soviets and the existence of Vladivostok as the most important Russian naval base in the Far East.

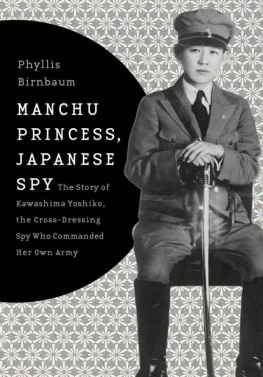

The political history of the northeast (Manchuria) has never been sufficiently democratic to permit the emergence through elections of popular figures among the Manchus and the Mongols to replace fully the concept of leadership vested in the theory of dynastic succession. This was one reason why the Japanese made Pu Yi Emperor of Manchukuo and sought to perpetuate and develop control of the dynastic inheritance through the marriage of his brother and heir to a Japanese noblewoman. Another reason was his utility as a device for potential Japanese expansion into Siberia and Mongolia, the Oriental populations of which could be expected to respond to the dynastic claims of Pu Yi as opposed to the colonial claims of Moscow. Pu Yi thus owed his fourteen-year restoration not, as he hoped, to the desire of the Japanese to obtain through him control of China proper, but to the intent of Japan to use him as an instrument of psychological warfare and subversion in order to win from Russia what Russia had once won from China. The Black Dragon Society was used by the Japanese imperialists to assist in the restoration of Pu Yi. It was a sort of Japanese CIA. It had always an anti-Russian direction and its name in the languages of the Orient, by a play on words, suggested Japanese expansion north of the Amur River into Siberia, not expansion south of the Great Wall into China itself.

This identification with clandestine and subversive efforts along the Sino-Soviet frontier explains Pu Yis importance as well as that of his heirs. His five-year imprisonment at the hands of the Soviets and more than nine-year detention by the Chinese Communists must be examined in the light of the relations between the two countries if the future is to be understood. The fact that Pu Yi has suggested that his brainwashing was something separate and personal, and divorced from outside events is unrealistican example of Maoist Communist policy of publicly emphasizing ideology as distinguished from practical politics in its effort to capture leadership of the international Communist movement.

The Yalta agreements of February 1945 created the opening pattern of Pu Yis incarceration, which began six months later. By these arrangements among the Western powers, which were later translated into an agreement between Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek, Outer Mongolia became independent of China, Manchuria became a Soviet sphere of influence and Port Arthur a USSR naval base. The Northeast and Pu Yis Manchu people reverted to the status they enjoyed before the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, when Russia rather than Japan enjoyed paramount interest over the area.

In view of this reversion of Manchurian suzerainty, it was only natural that when Japan was defeated in August 1945 and the monarchy crashed, Pu Yi passed from the protection of the Japanese to that of the USSR. This protection lasted from 1945 until July 31, 1950, when he was turned over to the Chinese Communists.

Meanwhile, the Northeast underwent a similar shift from Russia to China. October 1, 1949, marked the offical beginning of the Peoples Republic of China. Three months later Chairman Mao went to Moscow to confer with Stalin and brought home in February 1950 a treaty of friendship and alliance. Various concessions were made by the Soviets to their new ally, including the relinquishment of their special Manchurian rights. This was the heyday of Sino-Soviet cooperation and also the time when North Korea, at Moscows instigation, invaded South Korea and was joined in the war by the Chinese Communists.

At the same time, in the Thought Control Center in Fushun to which Pu Yi was consigned as a result of this Sino-Soviet accord, he experienced the most stringent remolding. Separated from his family, denounced by his nephews, deprived of all prerogatives, he became a nonperson. For if the Sino-Soviet frontier was to remain quiet, if there was to be no chicanery and subversion among the border peoples in the name of race, or nationality or color, then Pu Yi had no more utility than the curios and antiques he surrendered from time to time to his captors as a testimony of his devotion.

But on March 10, 1956, things began to improve for Pu Yi. His uncle, the former Prince Tsai Tao, was allowed to visit him in prison and give him news of the outside world and the status of the Manchu clans. Tsai Tao spoke of his election to the Peoples National Congress and adverted to visits he had made to the Northwest and of his work with national minorities. These words from the lips of the former senior royal prince of China, the brother of the former Prince Regent, the uncle of the last emperor, could only mean that Chairman Mao had decided by the mid-1950s, just as the Japanese had decided in the mid-1930s, that the Manchu Aisin-Gioro clan (royal family of China) could be useful along the frontier.

And thus, soon after Tsai Taos visit, Pu Yis treatment and that of the other Manchu detainees improved. By September 1959, Pu Yi again acquired a personality of his own. This occurred despite the fact that shortly before his pardon, the Prison Governor found him guilty of lying in order to curry favor with the authorities.

Meanwhile, and parallel to Pu Yis restoration as a person, Sino-Soviet relations deteriorated. In November 1957, the Soviet Union and Communist China signed the Moscow Declaration, which was an unsuccessful attempt to heal the ideological breach that was opening between the two countries. In 1960, shortly after Pu Yis release from prison, Chinese students were called home from Russia and Russian technicians were withdrawn from China. Trade between the two countries slumped from $2 billion U.S. in 1959 to less than $1 billion in 1961.