Acknowledgments

In the course of the fifteen years that I have worked on the project presented in this book, I have incurred deep debts to so many mentors, supervisors, colleagues, friends, and family members in China, South Korea, Japan, the United States, and other countries that I cannot list all their names here.

My thanks must first go to Jian Chen, Haijian Mao, Sherman Cochran, and Julien Victor Koschmann for their matchless academic guidance and strong support over the years. My sincerest gratitude is due to those senior researchers who have helped me to develop my project and enrich my ideas, including Young-seo Baik, Shangsheng Chen, Zhihong Chen, Yinghong Cheng, TJ Hinrichs, Douglas Howland, Isabel Hull, Nam-lin Hur, Chin-a Kang, Shin Kawashima, Seonmin Kim, Mio Kishimoto, Dorothy Ko, Bum-jin Koo, Kirk Larsen, Hun Lee, Dezheng Li, Yunquan Li, Ping Liu, Tianlu Liu, Zhitian Luo, Tobie Meyer-Fong, Yjir Murata, Mary Beth Norton, Takashi Okamoto, Myung-lim Park, Kenneth Pomeranz, Xiaoyan Rong, Naoki Sakai, Chengyou Song, Osamu Takamizawa, Yuanzhou Wang, Yuanfeng Wu, Jiashen Yang, and Zhiqiang Zhao.

My learned colleagues in the Department of History, the Program of Asian Studies, and the Center for Global and Area Studies at the University of Delaware have provided a stimulating academic environment from which I continue to draw inspiration. In particular, I have to thank Alice Ba, Anne Boylan, James Brophy, Eve Buckley, Jianguo Chen, Jesus Cruz, Rebecca Davis, Lawrence Duggan, Darryl Flaherty, Alan Fox, Christine Heyrman, Barry Joyce, Hannah Kim, Daniel Kinderman, Peter Kolchin, Wunyabari Maloba, Rudi Matthee, Mark McLeod, Arwen Mohun, John Montano, David Pong, Ramnarayan Rawat, David Shearer, Steven Sidebotham, Patricia Sloane-White, David Suisman, Douglas Tobias, Owen White, and Haihong Yang.

Numerous friends in different countries have supported my research over the years. Among them are Christopher Ahn, Eriko Akamatsu, Claudine Ang, Harutoshi Aoyama, Zhilei Bie, Michael Carpentier, Shiau-yun Chen, Jack Chia, Deokyo Choi, Danielle Cohen, Mari Crabtree, Brian Cuddy, Haibin Dai, Chennan Ding, Feng Feng, Xuefeng Gu, Kate Horning, Noriaki Hoshino, Zachary Howlett, Xiangyu Hu, Junliang Huang, Qixuan Huang, Hongwei Huo, Aimin Ji, Chen Ji, Huajie Jiang, Christopher Jones, Dong-hun Jung, Jason Kelly, Elli Kim, Hanmee Kim, Amy Kohout, Tinghui Lau, Peter Lavelle, Pyong-soo Lee, Seok-won Lee, Baoming Li, Gang Li, Shan-ai Li, Wenjie Li, Minling Liang, Joshua Van Lieu, Bensen Liu, Oiyan Liu, Wenli L, Jorge Marin, Hajimu Matsuda, Mayuko Mori, Huixiang Pan, Trais Pearson, Yuanyuan Qiu, Zhiyong Ren, Victor Seow, Nianshen Song, Ming Sun, Shichun Tang, Lesley Turnbull, Bo Wang, Haitao Wang, Qingbin Wang, Sixiang Wang, Dong Xu, Heng Xu, Jiguo Yang, Sungoh Yoon, Wei Yu, Hairong Zhang, Jianjun Zhang, Lei Zhang, Ting Zhang, Tingting Zhang, Jian Zhou, and Taomo Zhou. For more than a decade, Danielle Cohen, Zachary Howlett, and Nianshen Song have always read my chapter manuscripts and offered superb and interdisciplinary feedback, and I cannot thank them more.

It was an honor to be a fellow of the Korea Foundation and of the Japan Foundation, which funded my research at Yonsei University in Seoul and the University of Tokyo in Tokyo, respectively. Cornell University and the University of Delaware generously supported my overseas archival research in East Asia. The University of Delaware also offered strong support for the publication of this book. The staff members of the many archives, libraries, and research institutes that I visited in East Asia and the United States provided much-appreciated assistance. The publishers of two earlier articles kindly allowed me to include those articles in this book; they are Claiming Centrality in the Chinese World, Chinese Historical Review 22, no. 2 (2015): 95119, and Civilizing the Great Qing, Late Imperial China 38, no. 1 (2017): 11354. The critical comments of the anonymous reviewers of the two articles helped me improve the quality of this book.

I am delighted that this book found a home at Cornell University Press. Emily Andrew offered wonderful guidance and advice throughout the entire process. Bethany Wasik and Susan Specter helped me deal with many issues connected to the publication. The two dedicated anonymous reviewers read my manuscript with great care and provided outstanding and thought-provoking comments. Alice Colwell, Hanna Siurua, and Eric Levy provided brilliant suggestions in the process of polishing the manuscript.

Finally, I must express my heartfelt thanks to the members of my family, who resolutely supported my career during the years in which I studied and worked in different countries across the Pacific. This book is dedicated to all of them, in particular to my wife, Na, and my daughter, Yujia.

Note on Romanization and Conventions

This book follows the Pinyin romanization system for Chinese, Mllendorff for Manchu, McCune-Reischauer for Korean, and Hepburn for Japanese. The abbreviation Ch. refers to Chinese, Ma. to Manchu, K. to Korean, and J. to Japanese. A few established Wade-Giles spellings of Chinese figures, such as Sun Yatsen, remain unchanged. Several key Chinese, Manchu, and Korean terms, such as Zongfan, Zhongguo, Dulimbai gurun, Zhonghua , and Junghwa , are capitalized. The names of Manchu figures are spelled either in Mllendorff (when the Manchu characters are available) or in Pinyin (when they are not available). A core indigenous Chinese term, fan , which is often rendered as tributary state in English, always appears in italics. The Chinese and Korean dates of primary documents using the lunar calendar have been converted into their counterparts in the Gregorian calendar based on Jinshi Zhong Xi shiri duizhao biao (Cross-reference lists of modern Chinese and Western historical dates), edited by Hesheng Zheng.

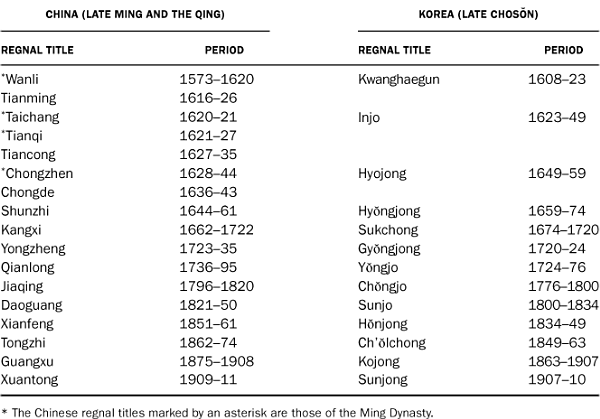

Chinese and Korean Reign Periods, 16001911

Introduction

Day dawned on April 25, 1644, in the seventeenth year of the reign of the Chongzhen emperor of the Ming Dynasty of China. As the first rays of the sun struck the walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing, a large group of rebels stormed the gates. Right before the rebels swarmed the imperial halls, the emperor managed to climb up an artificial hill behind the palace and hang himself from a tree. His loyal servant, a eunuch who had cared for the desperate thirty-three-year-old emperor since the latters birth, hanged himself from another tree. The Ming Dynasty, or the Great Ming, which had governed China for 277 years, came to a sudden end.

The Mings unexpected demise put one of its generals, Wu Sangui (161278), who was fighting on the front lines of an unrelated conflict about 190 miles east of Beijing, in an awkward position. General Wu was defending Shanhai Pass, a strategic military outpost of the Great Wall connecting inner China with Manchuria, in the war with the Qing, a regime founded in 1616 by the nomadic Manchus in Manchuria. The war had lasted for almost three decades, during which the Manchus had decisively defeated the Ming troops in Manchuria, subordinated neighboring Mongol tribes, and conquered the Chosn Dynasty of Korea, a loyal tributary state of China. Shanhai Pass became the last fortification preventing the formidable barbarians, as both Ming Chinese and Chosn Koreans regarded the Manchus, from entering inner China. As Beijing fell into the rebels hands, General Wu lost his country overnight. In Manchuria, the Manchu emperor seized the opportunity to send his troops under the leadership of Prince Dorgon (161250) to the outskirts of Shanhai Pass, where the army waited to cross the Great Wall to enter inner China. Meanwhile, the rebels in Beijing began to march toward the pass, with General Wus father as a hostage, in order to annihilate Wu. In this life-or-death situation, Wu chose the Manchus as his allies. He opened the giant gate to allow the Manchu forces to pass through the Great Wall and help him defeat the rebels.