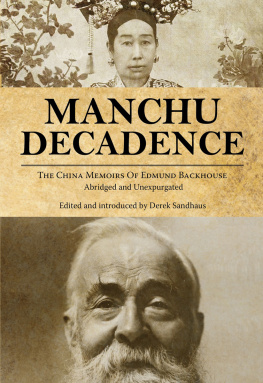

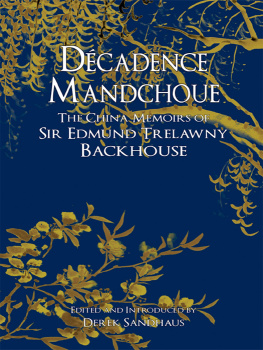

MANCHU DECADENCE

By Edmund Trelawny Backhouse

ISBN-13: 978-988-19982-8-6

2015 Earnshaw Books

Introductions Copyright Derek Sandhaus

HISTORY / Asia / China

First printing July 2015

EB067

Cover portrait of Edmund Backhouse (MS. Eng. misc. d. 1226, fol. ii) courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact

Published by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong)

C ONTENTS

E DITOR S N OTE TO THE N EW E DITION

T HE SPECTER OF Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse has long haunted Chinese history. Love him or hate him, trust him or not, his telling of the decline and fall of the Ching dynasty, as written in China under the Empress Dowager and Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking, is ingrained on our collective subconscious. Later historians, most famously Hugh Trevor-Roper in The Hermit of Peking, challenged Backhouses claims and sources, but could do little to contain his influence. Through insinuation and innuendo, occasionally from more respectable tongues, his stories live on. And this feels right. Whatever else the man waslinguist, historian, libertine or charlatanhe was a hell of a storyteller.

In the spring of 2009 publisher Graham Earnshaw approached me about editing Backhouses memoirs, Dcadence Mandchoue. Though it had at that point been gathering dust in Oxfords Bodlein Library for decades, few unpublished manuscripts had ever achieved such notoriety. Within its pages was the scandalous tale of a secret coup against the Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi and, more astonishing, the claim that Backhouse was her longtime lover. Needless to say, I could not wait to begin.

Though the highly sexualized content of the manuscript had made it categorically unpublishable when it was written in 1943, other considerations made it a difficult proposition for the modern publisher. The work comprised three drafts of varying legibility and intelligibility. It was cumbersome, multi-lingual and esoteric, an inscrutable work of soaring genius and endless digression.

We had to make a decision: authenticity or readability. We elected for the former. Given the controversial nature of the work and its author, this was essential. Readers had to be able to evaluate a version that coincided with the authors original vision as closely as possible, and our responsibility was to provide them with whatever clarity we could. It took two years, a team of translators and more than a thousand footnotes to render the first edition of Dcadence Mandchoue. It was unabridged in every sense, not intended for the faint of heart or short of time.

This edition is the other side of the coin. In fashioning it, I applied the same editorial rigor I would have had I been working with a living author. Everything written in another language, with very few exceptions, has been translated into English. Anything that required a footnote has been either amended or deleted. Some passages that were deemed distractingparticularly long meandering stretches in the second and nineteenth chapters, in which the author appears to be defending himself from his critics rather than advancing the narrativewere cut.

This book stands as a separate creation of our own, apart from the authors original work. We call it Manchu Decadence, resisting the original temptation to call it Backhouse under the Empress Dowager. Though less complete than the full edition, we believe that it remains in essence true to the original.

But readers of this edition are doubtless more interested in sensational revelations than in editorial nuance. You want to know about court intrigues, murders and the sexual mores of eunuchs. More to the point, you want to know whether or not Sir Edmund actually slept with the Empress Dowager.

At this far remove, one can do little more than speculate as to what really happened. Few illuminating facts have surfaced since the initial publication of Dcadence Mandchoue, nor are they likely to do so in the near future. I must confess that I, too, have at times harbored doubts as to the authors reliability. So I will answer the books central question as Backhouse would have: with a digression.

Just weeks after the publication of Dcandence Mandchoue I gave a talk to a Chinese history group in Shanghai. Afterwards, a woman approached me and invited me to present before a similar group in Beijing. The story of Edmund Backhouse was of personal interest, she explained, as she was a direct descendent of the imperial Manchu family. Looking at her round face with the deep-set eyes, I could swear there was a faint resemblance with Backhouses Old Buddha, Tzu Hsi. A remarkable coincidence, but this was in China, where strange things seem to happen all the time.

About half a year later, I was on a twin-prop plane in Laos. There were about twenty-five people on the flight, among them a British couple seated opposite my wife and me. They were older, but looked vital and well put together, as if plucked from a commercial for erectile dysfunction medication. After the flight, a driver was waiting outside of the baggage claim holding a sign with an unusual yet familiar English surname. I was sure I knew it from somewhere.

Excuse me, the woman said, interrupting my musing. That book you were reading, Im sure that I have read it. Could you remind me of the plot? So I did and, while I was speaking, it hit me.

This might be an odd question, I said, but are you related to Edmund Backhouse?

No, she replied. But my husband is. There was something unmistakably Backhousean about the whole affair. A hundred years and worlds apart from the fin-de-sicle Peking of Dcadence Mandchoue, the descendents of the eccentric Englishman and his Imperial Manchu lover had begun coalescing around the tales credulous editor. It was all a bit much. I could almost hear the ghost of Sir Edmund laughing at me.

What I would suggest then is not that Backhouses memoirs represent a true, unembroidered account of the facts, but that readers would be unwise to dismiss them out of hand for their outrageousness. Coincidences do happen. They are the stuff of everyday life and without them very few tales would be worth telling. Even if one considers this book a work of pure imagination, it is still a delightfully entertaining narrative, an eccentric genius masterwork well seasoned with colorful musings and bawdy anecdotes. In a word, it is a book that deserves to be read.

In closing I would make one final suggestion: If one plans to bed foreign royalty and brag about it later, best take pictures and get a signed affidavit. Your future publisher will thank you for it.

Derek Sandhaus

Buenos Aires

March 2015

I NTRODUCTION

B Y THE E DITOR

I N 1939, a mysterious old man moved to the Foreign Legation Quarter of Japanese-occupied Peking. Dressed in an ankle-length robe with a long white beard and a brimless cap adorned with a large red gemstone, he could easily have been mistaken for an aging Chinese gentleman. He spoke the northern dialect beautifully and addressed the local servants with a familiarity that must have seemed shocking to the foreign residents of the Legation Quarter meeting him for the first time.

But the man was not Chinese, he was an Englishman, once one of the most famous foreigners in all of China. After years of quiet scholarship on the western edge of the city, he had abandoned his home and possessions, believing that the Japanese occupiers had left him no choice but to seek refuge elsewhere. As in 1900, when the Boxer and Manchu soldiery laid siege to the Legation Quarter demanding foreign blood, the threat of violence had driven him to rejoin his compatriots.

Next page