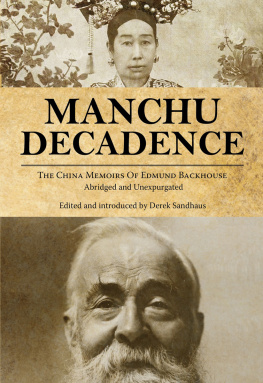

DCADENCE MANDCHOUE

Edmund Trelawny Backhouse (1943)

Edited by Derek Sandhaus

Edition copyright 2011 Earnshaw Books

ISBN-13: 978-988-19445-1-1

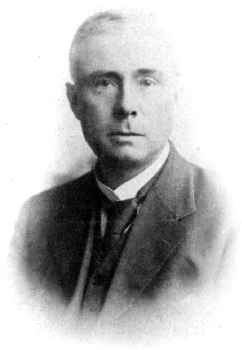

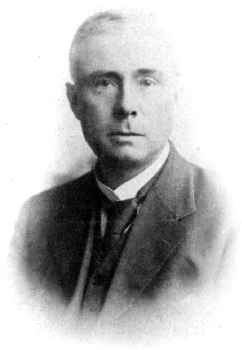

Cover portrait of Edmund Backhouse (MS. Eng. misc. d. 1226, fol. ii), image of Edmund Backhouse on his deathbed (MS. Eng. misc. d. 1225, fol. 237), and three images of the original Dcadence Mandchoue manuscript (in order of appearance, MS. Eng. misc. d. 1224, fols. 32 and 400; MS. Eng. misc. d. 1226, p. 326) courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Image of Edmund Backhouse in the early nineteen-forties courtesy of Tom Cohen.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact info@earnshawbooks.com.

Published by Earnshaw Books (Hong Kong).

Edmund Backhouse in his mid-forties

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION B Y THE E DITOR

I N 1939, a mysterious old man moved to the Foreign Legation Quarter of Japanese-occupied Peking. Dressed in an ankle-length robe with a long white beard and a brimless cap adorned with a large red gemstone, he could easily have been mistaken for an aging Chinese gentleman. He spoke the northern dialect beautifully and addressed the local servants with a familiarity that must have seemed shocking to the foreign residents of the Legation Quarter meeting him for the first time.

But the man was not Chinese, he was an Englishman, once one of the most famous foreigners in all of China. After years of quiet scholarship on the western edge of the city, he had abandoned his home and possessions, believing that the Japanese occupiers had left him no choice but to seek refuge elsewhere. As in 1900, when the Boxer and Manchu soldiery laid siege to the Legation Quarter demanding foreign blood, the threat of violence had driven him to rejoin his compatriots.

Soon after the start of the Pacific War a couple of years later, another Legation Quarter resident, a Swiss physician named Reinhard Hoeppli, passed the man in his rickshaw. Hoepplis Manchu rickshaw puller, upon noticing the man, informed Hoeppli that they were in the presence of greatness. The man they had passed, the rickshawman said, was rumored to have once been the lover of the late ruler of all China: the Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi. His name was Edmund Backhouse.

Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse, a British baronet of well-established Quaker ancestry, was born in Richmond, Yorkshire in 1873 and educated at St. Georges School, Ascot; Winchester College and later Oxford University. He failed to complete his undergraduate studies, but he was a voracious learner with a rare gift for languages. By the time he arrived in Peking in 1898, he professed fluency in French, Latin, Russian, Greek and Japanese. Less than a year later, he was working as an interpreter and informant for The Times and the British Foreign Service. No one in Peking, wrote Dr. G.E. Morrison of The Times, approaches him in the ease with which he can translate Chinese. In 1903 the Chinese government appointed him professor of law and literature at the Imperial Capital University (later known as Peking University). A year later, we find him as an agent of the British Foreign Office, gaining fluency in Mongolian and Manchu.

The crowning moment in Backhouses career came in 1910 when, together with another Times correspondent, J.O.P. Bland, he published China under the Empress Dowager. This book provided readers with the first comprehensive look at the last great ruler in Chinese imperial history as she presided over a tottering Ching Dynasty. Written in an accessible and entertaining style, the book contains an incredible depth of knowledge, owing largely to the books central text, The Diary of His Excellency Ching Shan, supposedly discovered by Backhouse during the looting that followed the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. An international bestseller, the book was declared a masterpiece and when the Ching Dynasty collapsed a year later, its reputation, and Backhouses too, seemed unshakeable.

This was just the beginning of the story. Sir Edmund co-authored another book with Bland, Annals & Memoirs of the Court of Peking (1914), also highly regarded for its scholarship, and donated a large collection of valuable printed Chinese books, together with a few scrolls and manuscripts, to the Bodleian Library at Oxford between 1913 and 1922. In 1918, working with Sir Sydney Barton, he completed a revised version of a Chinese-English colloquial dictionary by Sir Walter Hillier, a respected diplomat and sinologist. It was on Hilliers personal recommendation that Backhouse was also appointed chair of the Chinese department at Kings College, London, but he was unable to fill the position on account of ill health.

Backhouses contemporaries described him as eccentric, soft-spoken, polite and exceedingly humble. He was a charming and engaging conversationalist, yet he was also a recluse. For almost all of his 45-odd years in Peking, he lived far away from the protective bubble of the Foreign Legation Quarter. Abandoning the dapper style of his earlier years, he adopted Chinese dress and customs. He went out of his way to avoid contact with Westerners in the city, sending servants ahead to places he intended to visit to make sure there were no foreigners present. He even went so far as to cover his face when passing foreigners in a rickshaw. Yet despite these quirks, almost all who met Backhouse found him hospitable and entertaining.

After his death in January 1944, Backhouse seemed destined to pass quietly into respectable obscurity. He may have done just that if not for British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

In 1976, Trevor-Roper published A Hidden Life: The Enigma of Sir Edmund Backhouse (later republished and more commonly known as Hermit of Peking), but few had suspected him of being the forger. Trevor-Roper not only accused Backhouse of deliberately playing a role in the diarys fabrication, but also uncovered evidence indicating a pattern of fraud and deceit in other realms. He showed that Backhouse repeatedly lured people into bogus business ventures, ranging from the sale of nonexistent imperial jewelry all the way to covert international arms transactions using fictitious weapons shipped on imaginary boats. Backhouse was able to get away with it, says Trevor-Roper, because the foreign community was ill-informed about China and inclined to believe the treachery of the Orientals as the primary cause of any wrongdoing.

The most shocking revelation in Trevor-Ropers book was that Backhouse had, in his final year, authored two outrageous and obscene autobiographical manuscripts, The Dead Past and Dcadence Mandchoue. In these, his memoirs, Backhouse chronicled his youth in England and Europe (The Dead Past), and his life in China during the twilight years of the Manchu Ching Dynasty (Dcadence Mandchoue). He claimed not only to have met many of the most notable literary and political figures of his era, but also to have slept with them. In often highly graphic detail, Sir Edmund recounted his sexual escapades with personages including Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Paul Verlaine and Prime Minister Salisbury. The love affairs to which he confessed were almost exclusively homosexual, with one notable exception: Chinas longtime despot, the Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi, who died in 1908.