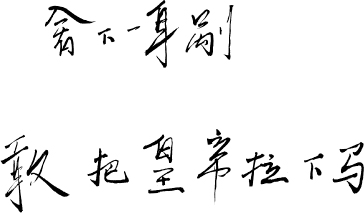

Throwing the Emperor from His Horse

Throwing the Emperor

from His Horse

Portrait of a Village Leader in China,

19231995

Peter J. Seybolt

First published 1996 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Seybolt, Peter

Throwing the emperor from his horse: portrait of a village leader in China, 19231995 / Peter J. Seybolt.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8133-3130-7 (hc)ISBN 0-8133-3131-5 (pb)

1. Wang, Fucheng, 1923-1925. 2. Houhua Village (China)Biography. 3. Houhua Village (China)History. I. Title.

CT1828.W318S49 1996

951.18dc20

[B]

96-32797

CIP

Text design by Heather Hutchison

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-3131-7 (pbk)

For Cynthia

At the risk of death, dare to throw the emperor from his horse.

The title of this book is taken from a traditional Chinese aphorism based on the Confucian principle that a person of integrity, that is, one who acts in accordance with universal moral imperatives, will have the courage to risk his life challenging those in positions of authority who are misusing their power. Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party of China, quoted the aphorism during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s when exhorting people to overthrow the president of the country, Liu Shaoqi, and other leaders in the Party and government whose policies, he said, were counterrevolutionary. Wang Fucheng, the principal subject of this book, knew little of the political disputes that divided the top leadership of the Communist Party, but he admired the aphorism for its emphasis on integrity and couragetwo personal characteristics that he sought to emulate as leader of his village. It was one of only two quotations from the sayings of Chairman Mao that Wang could remember when I interviewed him in the early 1990s.

Contents

Maps

China

Neihuang County

Liucun Township

Photos

Wang Fucheng,* the subject of this book, was born in 1923. For most of his life he lived in Houhua Village in northern Henan Province. His name does not appear in Chinese biographical dictionaries. It is not even included in accounts of prominent people in the local county gazetteer. Only in his village and the immediately surrounding area was he known. Within that small world he was respected but not famous. For thirty years, 19541984, he was Communist Party branch secretary, the highest office in his village. He served with competence, even distinction, though the scope of his activities and range of knowledge were limited by his total illiteracy.

Wang Fucheng knew little of the world beyond his village. Until the Communist Party introduced a campaign to criticize Confucius in 1971, Wang had never heard of the sage or his teaching. Even afterward, he still knew Confucius only by the deprecating title Kong lao er [Kongs second child] and was ignorant of when he lived or what he did. The best Wang Fucheng could offer when asked about Confucius was the remark, I heard he was a big capitalist and landlord from Shandong Province who didnt participate in manual labor. Despite his official position in the Communist Party, Wang Fucheng was ignorant even of the names of many top Party leaders. Before I arrived in Houhua Village, Wang Fucheng had never seen a foreigner and had no idea of foreign ways. When I talked with officials of Liucun Township, the administrative level above Houhua Village, they wondered why I had chosen to write about Wang Fucheng. They made it clear that in their opinion there was nothing very special about him, and they conceded only that he is a good example of local leadership from among the people.

One might well ask, Why write a book about Wang Fucheng and Houhua Village? What is significant about this man and this place? The answer requires some explanation.

In 1987 I went to northern Henan Province to study the effects of the War of Resistance (19371945) was too good to miss.

With the generous assistance of faculty in the History Department at Zhengzhou University (in Zhengzhou City, capital of Henan Province) I began collecting and reading materials on the history of northern Henan. I then took up residence in Puyang, a new city that has become the administrative center of the recently developed oil-drilling industry on the central plain of north China. From Puyang, I planned to travel to nearby villages of the sand region to interview peasants who remembered the war years. The sand region is distinguished by alluvial deposits from the Yellow River that formed when the river flowed through the area a millennium earlier. The quality of the fine, gritty soil is poor, but the wind-blown dunes and the Chinese date trees that grow on them provided rare cover on the otherwise flat plain for guerrilla activities during the war. The Communists had been especially active and successful there, and thus the area was of particular interest for my study.

Arranging village interviews in the sand region was no easy task. One first had to obtain permission from successive levels of the bureaucratic hierarchy, from province to county to township to village. Below the provincial level, all contact was in person, partly because that is the Chinese way and partly because mail service was slow and unreliable and telephones rarely worked. Making arrangements at county and township levels usually included an elaborate luncheon banquet at which there was much drinking and toasting, followed by a two-hour nap, before an agreement was reached. The process was frustratingly slow, though I must admit that the food was often superb.

Travel from Puyang into the surrounding countryside in 1987 was an adventure. The only paved roads at that time were those connecting the city with surrounding county seats. For reasons known only to local planners, all paved roads in the area were being repaired at the same time that summer, eliminating the possibility of unimpeded detour. Traffic was expected to wait patiently until a section of road was completed. Delays of several hours were common. The only recourse was to take unofficial detours through the dirt roads of the villages. In the sand region, those village roads are little more than paths that become dust traps when dry, and muddy quagmires when soaked with rain. Four or five times a day our vehicle got bogged down, and we were required to shovel and push. The peasants in the villages were furious as they watched their crops being destroyed and trees broken by detouring traffic. Some put up barriers, and others tried to collect fees from motorists. In one village through which we passed late one night in a heavy downpour the peasants had dug a trench five feet wide and five feet deep across the road. We saw it in time to avert disaster, but for an hour we had to shovel mud in the pouring rain before we could proceed.