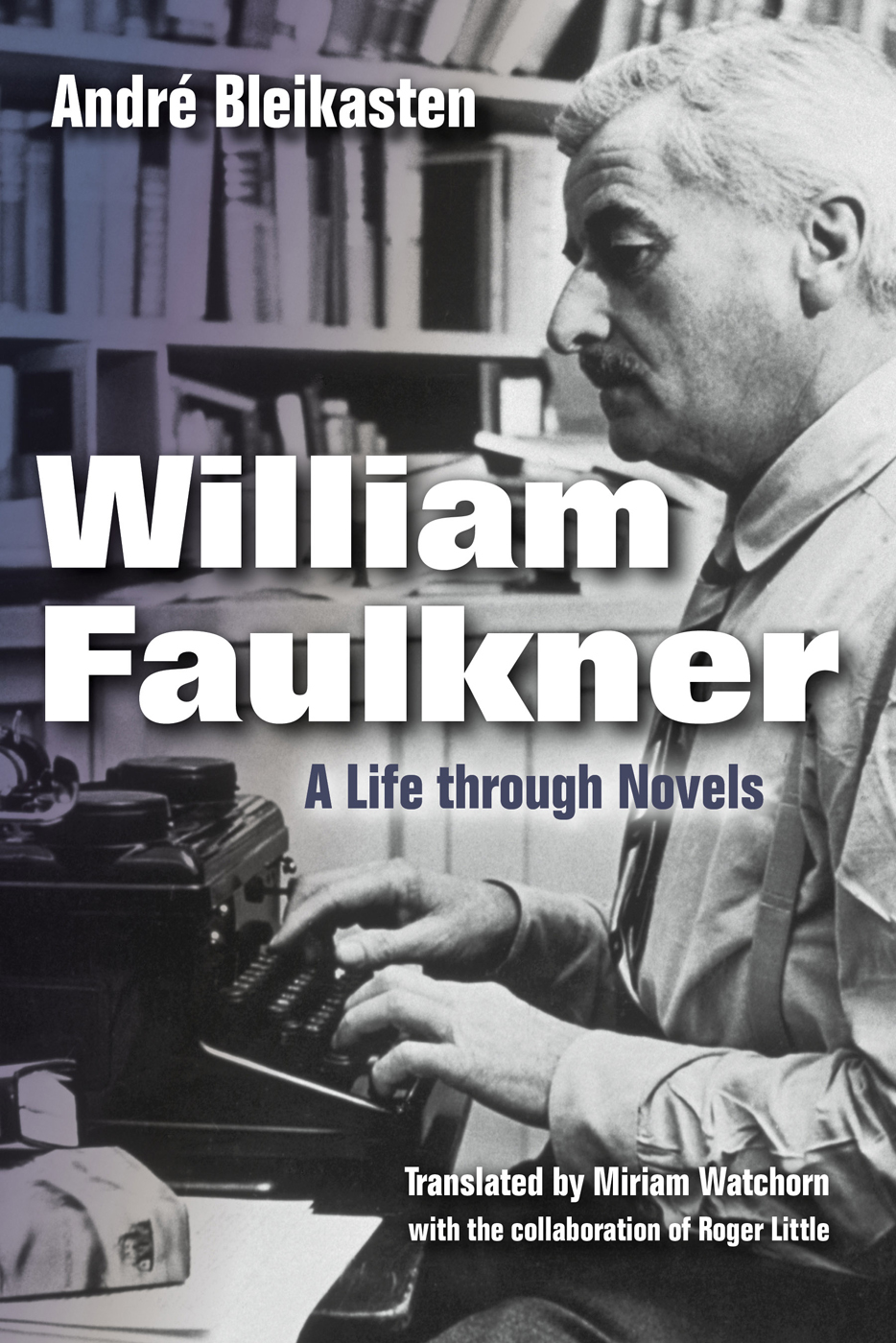

William Faulkner

Andr Bleikasten

William Faulkner

A Life through Novels

Translated by Miriam Watchorn

With the collaboration of Roger Little

Foreword by Philip Weinstein

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Aime Bleikasten

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02284-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02332-2 (ebook)

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

THE GREAT NINETEENTH-CENTURY French romantic Chateaubriand titled his last work Mmoires doutre tombe. In English this is rendered as Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, but the titles deeper resonance suggests memories clarified, sifted, accessed by way of some ultimate light. Andr Bleikastens William Faulkner: A Life through Novels recalls Chateaubriands work in a couple of ways. It is appearing in English seven years after Bleikastens death. More pertinently, it bears (page after page) the overwhelming impress of Bleikastens authority. Over the course of his thirty-five years of publication devoted to Faulkner, Bleikasten, though French, became the most distinguished interpreter of Americas greatest twentieth-century novelist. His William Faulkner: une vie en romanswhich was handsomely recognized by the Acadmie franaise when it first appeared in France (2007)is Bleikastens magnum opus.

The word overwhelming is not an adjective normally bestowed on commentary on fiction. With respect to Faulkner, we are likely to find it only in a few of his critics, and it turns out that these are mainly French. Malraux, Camus, and especially Sartre were the philosophical thinkers who recognizedas early as the 1930sthe extraordinary provocations wrought into Faulkners art. They saw in him not a Southern writer, and even less a race writer, but rather a metaphysical novelist, a supremely modern writer.

Faulkners American critics (from George Marion ODonnell in the 1930s through Cleanth Brooks in the 1960s) were mainly concerned with interpreting him as a regional figure. Not until John Irwins Doubling and Incest / Repetition and Revenge (1976) and John Matthewss The Play of Faulkners Language (1982) did Faulkners investment in the philosophical conundrums of his century begin to receive the attention they deserved. Irwin stressed Nietzsche and Freud as Faulkners imaginative precursors. Matthews identified Derridas problematic of language as an enabling lens for grasping the stakes of Faulkners experiments with narrative. In Nietzsche, Freud, and Derrida we see the literary turn toward critical theory that flourished in America throughout the 1970s and 1980s. But Bleikasten was there ten years earlier. To do justice to the thinking he draws on, we must add the names of Blanchot, Barthes, Lacan, and Foucault (the French component), as well as those of Jakobson and Chomsky (the poetics of language), Hegel (the drama of consciousness), and Bakhtin (the dialogic tensions that keep Faulkners prose fiercely self-embattled). This is not to speak of the relevant body of criticism devoted by American academics to Faulkner; for decades he was wholly familiar with its output as well.

My verb above is draw on. It is impossible to peg Bleikasten as an exponent of any of the critical and philosophical voices he learned from as he produced his own. Indeed, one of his most memorable critical performances occurred at the Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference held in August 2000 in Oxford, Mississippi. The weather at that time of year tends to vary from very hot to intolerably hot. Bleikasten gave his talkFaulkner in the Singularon perhaps the hottest day of the conference (I was there when he spoke). But the greater heat that day radiated, arguably, from the challenged band of critics in that audience: a sample of Faulkners ablest commentators, for the most part an angry crew. With customary fearlessness, Bleikasten had called into question their predictable devotion to currents of thought imported from European (mainly French) quarters. Bleikasten was not opposed to these currents of thought; he knew them upside down. The key texts of psychoanalysis, linguistics, poetics, and sociology were all familiar to him. He (probably the only one in that room) had read them in their original languagein his formative years in the 1950s and 1960sand they deeply informed his thought. But they did not foretell where his thought was headed. They did not testify to a Foucauldian or Lacanian or Derridean reading of Faulkner whose lines of development were predictable in advance. Bleikasten found it deplorable to attach Faulkners remarkable texts (in wholesale manner) to bodies of thought that, however seductive, were foreign to Faulkners own deployment of language. His entire career was devoted to Faulkner in the Singulara Faulkner whose resonance, richly illuminated by the largest range of modern thinkers, was finally a resonance all its own.

Bleikasten was born in Strasbourg, France, in 1933, and he was quick to say that Alsatian history had marked him for life (even as northern Mississippis history had marked Faulkner for life). The young Bleikasten grew up at home in both French and German; English was his third language, a latecomer. (But what English he was capable of writing!) As an Alsatian, he experienced World War II from dizzyingly close up: one uncle was murdered by the Nazis; another was decorated by them. One of Bleikastens salient memories dates from 1945, when (as a grateful twelve-year-old) he watched the GIs liberating Strasbourg, passing out chocolate and chewing gum as they walked the streets. Bleikastens love affair with Faulkners work does not grow directly out of this affection for the Yanks. It would take another seventeen years before he signed on to his doctorat dtat on Faulkner. But his undeviating admiration of American courage and spirit probably dates from Americas leadership role in World War II as well as from its generous international politics in the decade that followed.

Bleikasten was from the beginning a brilliant student, drawn especially to the humanities. Soon his research interests were devoted to literature written in English, with a focus on British fiction. In fact, he was set to write a dissertation on the novels of D. H. Lawrence, a preference that sheds a certain light on Bleikastens cast of mind. In Lawrences work he would have found passion (similar in some ways to the passion he found in Faulkner). No less, he would have found a mind-set rooted deeply in country rhythms, committed to unearthing men and womens deepest motives. Lawrences work centered on psychic struggle; his characters labor to free themselves. When on receiving the Nobel Prize in 1949 Faulkner described his abiding concern as the human heart in conflict with itself, he could have been speaking about Lawrence. In one of Bleikastens many irreplaceable essays, he compared the temperature of writers, noting that while Joyce and Mann were cool, Faulkner was hot. Hot in the sense that Faulkner grasps his people in life-or-death situations. Hot as well, perhaps, in Faulkners capacity to enter wholly into the mind-set (and heart-set) of his characters. Not to argue on their behalf, but (as a writer) to

Next page