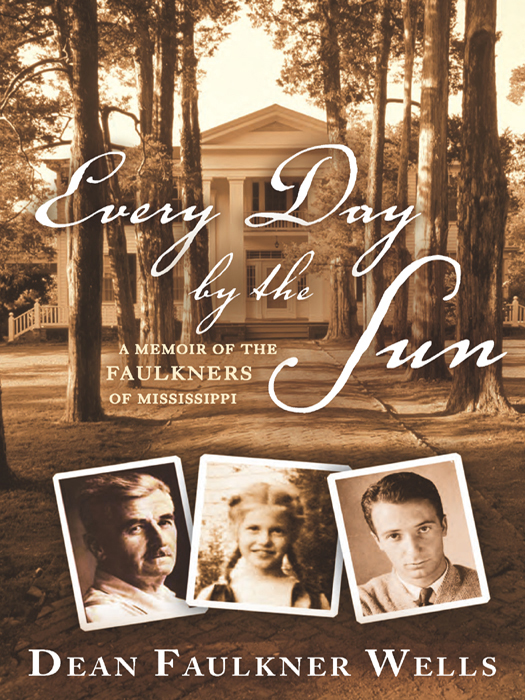

Copyright 2011 by Dean Faulkner Wells

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Parts of the Christmas story on first appeared in Mississippi Magazine, December 1987.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wells, Dean Faulkner.

Every day by the sun: a memoir of the Faulkners of Mississippi / by Dean

Faulkner Wells.1st ed.

p. cm.

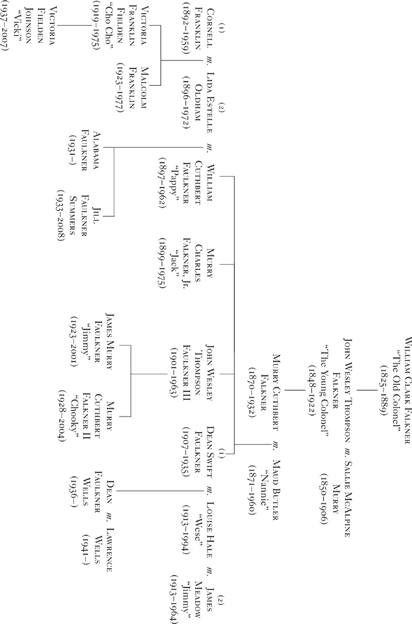

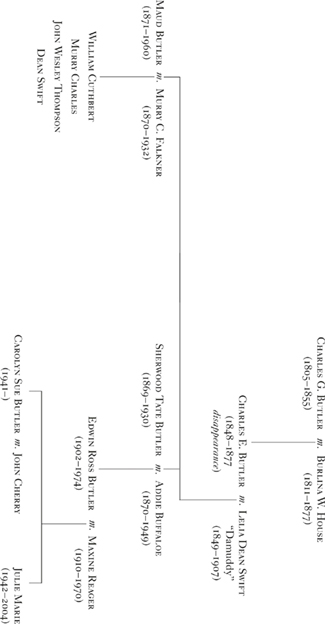

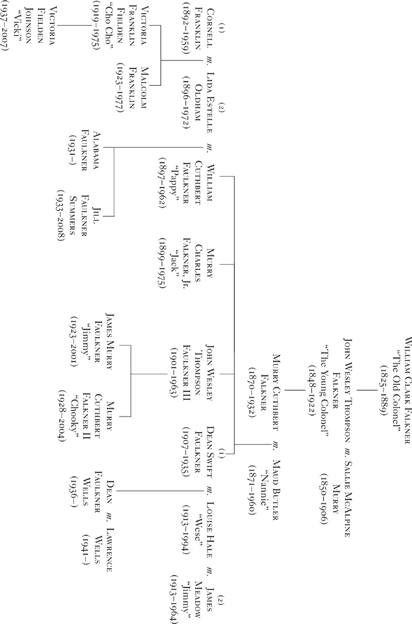

1. Faulkner family. 2. Wells, Dean Faulkner. 3. Wells, Dean

FaulknerFamily. 4. Faulkner, William, 1897-1962. 5. Faulkner,

William, 1897-1962Family. 6. MississippiBiography. I. Title.

CT274.F377W45 2011

920.0762dc22 2010031684

eISBN: 978-0-307-59106-7

Title page photograph Buddy Mays/ CORBIS

Jacket design by Jennifer OConnor

Jacket photographs: Kevin Fleming/CORBIS (house), courtesy of the author (portraits)

v3.1

Larry

Dean never needed a watch. He lived every day of his life by the sun.

FAMILY MEMBER SPEAKING OF D EAN S WIFT F AULKNER

T HE BEST AND THE WORST THING THAT COULD HAVE HAPPENED to me took place on November 10, 1935, four months before I was born, when my father, a barnstorming pilot, was killed in a plane crash at the age of twenty-eight. The best, because it placed me at the center of the Faulkner family; the worst, because I would never know my father.

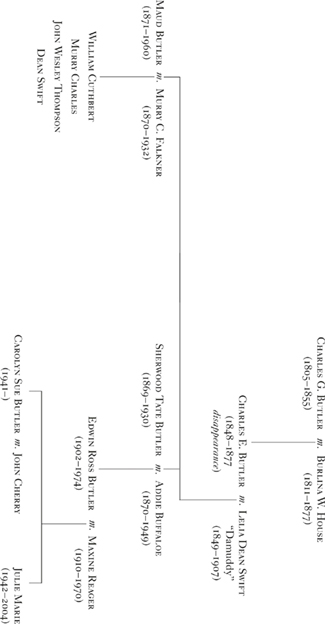

He was Dean Swift Faulkner, the youngest of the four Faulkner brothers of Mississippi: William, the future Nobel Prize winner in literature; Jack, an FBI agent; and John, a painter and writer. All four were pilots. Dean was the baby of his generation as I am in mine. His death defined my position in the family. I became more than just another granddaughter or niece. I was the last link to my father, and since he was gone, the people who loved him so dearly cared for me in his stead; they did the best they could for me. Due to an accident of birth I belonged to all of them, but it was Deans oldest brother, William, who felt the heaviest responsibility for me. He encouraged Dean to learn to fly, paid for his lessons, gave him a Waco C cabin cruiserWilliams own planeand with it a job at Mid-South Airways in Memphis, Tennessee.

After Deans death, William suffered from grief and guilt I imagine almost every day of his life. He attempted to assuage the pain by offering me security, both emotional and financial, whenever he could. It was as if William made a vow to Dean that November afternoon when he saw his unrecognizable body in the wreckage of the plane: He would tend to me in Deans place. He fulfilled his promise, and I grew up calling him Pappy.

Cherished by my family as an extension of my father, I have had to struggle to find my identity. My search for who I am started when I began to research my fathers life. His influence on me could not have been stronger had he lived. And as Pappys fame grew, of course we were all touched by it.

In 2010, I became the oldest surviving Faulkner in the Murry Falkner branch of the family. My fathers first cousin, Dorothy Dot Falkner Dodson, daughter of Murrys brother, John, died January 23, 2010. We were the only remaining family members with firsthand memories of the long dead people who shaped and supported the man who is arguably the finest American writer of the twentieth century. Now I am, one might say, the last primary sourceand I dont like anything about it. By the time I reached seventy, I expected to be transformed into Miss Habersham, Aunt Jenny, Granny Millard, or, if I was lucky, Dilsey. I believed with all my heart that to grow older was to grow wiser. I am living proof that this aint so. (Note that throughout Im using Pappys preferred aint, without the apostrophe.)

My relatives were private people, building walls not only to shield themselves from outsiders but from one another. This vaunted Faulkner privacy, which has been interpreted as anything from crippling shyness to arrogance to paranoia, may have evolved as a safety hatch in light of our eccentric and sometimes outrageous behavior.

Over the generations my family can claim nearly every psychological aberration: narcissism and nymphomania, alcoholism and anorexia, agoraphobia, manic depression, paranoid schizophrenia. There have been thieves, adulterers, sociopaths, killers, racists, liars, and folks suffering from panic attacks and real bad tempers, though to the best of my knowledge weve never had a barn burner or a preacher.

The only place we can be found in relative harmony is St. Peters Cemetery in Oxford, Mississippi. Yet there we cant even agree on how to spell our name. It appears as FALKNER on several headstones; in the next plot FAULKNER; in the main family plot both FALKNER and FAULKNER, buried next to one another; and one grave marker reads FA(U)LKNER. It is obvious that though there were not many of us to begin with, weve never been a close-knit family. We are prone to falling-outs, quick to anger, and slow to forgive. Whereas most families come together at holidays or anniversaries, ours rarely has, at least not in my generation. With the exception of our immediate kin, weve been derelict in keeping up family ties.

Pappy tried. On New Years Eve in the 1950s, he liked to host small gatherings for family and friends at his home, Rowan Oak. Dressed to the nines, we met shortly before midnight in the library, where magnums of champagne were chilling in wine coolers, and crystal champagne glasses were arranged on silver trays. As the hour approached, Pappy moved about the room and welcomed his guests. When our glasses were filled he would nod at one of the young men standing near the overhead light switch. Then he would take his place in front of the fire. When the lights were out and the room was still, with firelight dancing against the windowpanes, Pappy would lift his glass and give his traditional New Years toast, unchanged from year to year. Heres to the younger generation, he would say. May you learn from the mistakes of your elders.

Im still learning.