FOR

PAULA MARIA

AND

GEBRIL

Contents

Introduction

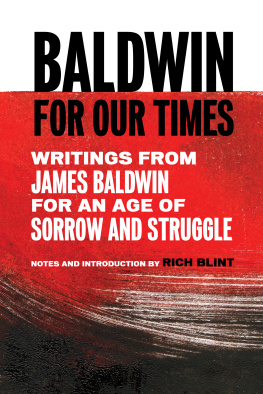

I did not know James Baldwin the essayist before my first year of college. I knew only the James Baldwin of novels and short stories and plays, a trusted man who gave me, with his Harlem and his Harlem people, the kind of world I knew so well from growing up in my Washington, D.C. They were all one family, the people in Harlem and the people in Washington, Baldwin told me in that way of all grand and eloquent writers who speak the eternal and universal by telling us, word by hard-won word, of the minutiae of the everyday: The church ladies who put heart and soul into every church service as if to let their god know how worthy they are to step through the door into his heaven. The dust of poor folks apartments that forever hangs in the air as though to remind the people of their station in life. The streets of a city where the buildings Negroes live in never stand straight up but lean in mourning every which way.

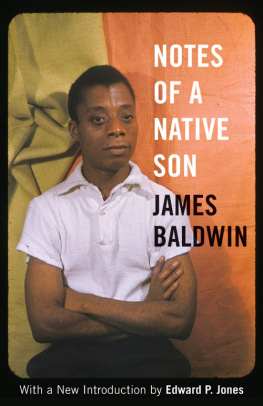

So I knew this Baldwin and, in that strange way of members of the same family, he knew me. When I went off to college in late August 1968, I took few books, anticipating the adequacy of the library that awaited me at Holy Cross College. I packed only two books of nonfiction, both bought in a used bookstore not long after I was accepted to college. Both had never been read. The first was a ponderous 1950s tome on writing logical and well-reasoned essays. I was never to read it in my time at Holy Cross, perhaps because it was so inaccessible. (Seeing it on my dormitory rooms bookshelf, Clarence Thomas, a month before his graduation from Holy Cross in 1971, purchased the book from me for $5; I do not recall what I paid for it.) And the second was Notes of a Native Son. I was going off to a new life, a life of the mind and education among white people, and I felt that since Baldwins fiction had taught me so much about black people, his essays might have a similar effect given where I was going.

I entered Holy Cross as a mathematics major, primarily because I had done well in math in high school. I was extremely shy then, and I had never had my vision tested and did not know enough about anything to realize that my frequent inability to see the blackboard could be solved with eyeglasses. I sat in the back of the freshman calculus class run by a standoffish professor who spent most of the period with his back to his students as he wrote on the blackboard, and with all of that, I fell further and further behind as the semester progressed.

I will go into English, I told myself in December, knowing how much I loved to read and knowing that a calculus D was coming and so there would be no life in mathematics. Before leaving for Christmas vacation, I picked up Notes of a Native Son for the first time, perhaps understanding that now my life would be increasingly one of essay writing. The first thing James Baldwin tells me in Autobiographical Notes is, I was born in Harlem. A simple, unadorned statement, as if in saying it plainly the reader would have a better sense of the importance of that fact. It was Harlem, but because I was so familiar with the Baldwin of fiction, the Baldwin whose black people could be Washingtonians, he could only have begun to connect in a better way if he had said, I was born in Washington, D.C.

A good bit of that introductory essay deals with being a writer, something that would not have much meaning for me for many years: the necessity of delving into oneself to be able to tell the truth about the world one writes about; the difficulties of being a Negro writer when the Negro problem is so widely written about; the desire, at the end of the day, to be a good writer.

But within that short essay is a thirty-one-year-old, somewhat worldly man (I did not get my first passport until I was fifty-four) who is still grappling with having been born into a small and often less than caring world, which was, for good or bad, a part of a larger world that generally rejected him and his small world. I was a Holy Cross studentoften happy to be a student at the Crossbut I knew every time I stepped out of my room in Beaven dormitory that no part of that place in Worcester, Massachusetts, had been made with me in mind. I felt that but did not yet have very many words for it. Baldwin gave them to me. This is Baldwin, with his special attitude, talking of Shakespeare and the cathedral at Chartres and Rembrandt and the Empire State Building and Bach: These were not really my creations, they did not contain my history; I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself. I was an interloper; this was not my heritage.

And so he continued throughout the rest of Notes, a gloriously keen and sensitive mind, something I did not completely appreciate at the time, something Im sure he would smile about now. I confess that I could not then grasp some of his more complex thoughts, perhaps because I was merely too young and the world had yet to take such a harsh hold on me. And other thoughts of his I just dismissed, no doubt because I was, again, too young and because I was developing a militant streak that scoffed at notions not in line with my own developing ones. That militancy came naturally with the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Vietnam War and with the new awareness that I was black in a white world. The militant me asked, for example, why would Baldwin write at times as if he were not black but some observer, a guilty one, true, but still an observer. Our dehumanization of the Negro then, he says to me in Many Thousands Gone, is indivisible from dehumanization of ourselves: the loss of our own identity is the price we pay for our annulment of his. And later: We (Americans in general, that) like to point to Negroes and to most of their activities with a kind of tolerant scorn.

But with my focus on the constant use of words like we and our, it was easy for eighteen-year-old me in those last days of December 1968 to lose sight of so much of the truth and pain of that and other statements in Thousands. People, I have learned, have a way of taking root in ones still-developing mind without our knowing it, especially people, like Baldwin, who live in the world of words. How else, then, to explain my every effort to tell in a novel as best I could the stories of slave masters, black and white, and how slavery crushed their souls every morning they got up from their beds and thanked their god for their dominion over others. If I knew the importance of telling that, it was because Baldwin and his kind had planted the idea long ago. (I give him so much credit because he was in the minority of all the black writers I was reading who understood the importance of giving white people their due as full-fledged human beings. Even before I knew I would get into this writing thing, Baldwin told me this: You do not have to fully humanize your black characters by dehumanizing the white ones.)

Traveling with Baldwin through Notes The Harlem Ghetto, Journey to Atlanta, and Notes of a Native Son, I was given a grander portrait of the man I had known only through fiction. His fiction certainly had an unprecedented and absolute life of its own, and I might have tried to imagine the man I was dealing with, but those essays afforded me something beyond the postage stampsized pictures of him and the few sentences of biography that came with my paperback editions of, say, Go Tell It on the Mountain or Another Country. He would have been Baldwin had I never read those essays, but he would not have been real enough to deign to share a moment or two with me. The fiction offered a person of enormous humanity. The essays offered a man, a neighbor, or, yes, an older brother.

Next page