Baldwin for Our Times

Writings from James Baldwin for an Age of Sorrow and Struggle

Notes and Introduction by Rich Blint

Beacon Press, Boston

Sufficiently Hungry to Be Dangerous

James Baldwin and Race in Twenty-First-Century America

There is a recurring phrase in James Baldwins body of work that captures that moment of origin and nascent conscience when one opens ones eyes on the world. The language is stark and irreducible, as he might note, a necessary, matter-of-fact description of so common and monumental an action. With characteristic rhetorical economy, Baldwin is able to conjure that moment when each of us opened our eyes dimly, in some corner of this increasingly troubled planet, before the magic and mystery of human living. That this deeply existential reality is, of course, common to us all is worthy of remark if only as a timely reminder that we are, in ways spiritual and actual, blood relations. But it is also useful emphasizing what strikes many as obvious: through the dramatic accident of time and space, we enter the world in particular places, bodies, and with varied relationships to the habits of power and social structures we inherit and invariably confront.

This fact is at odds with the ethos and tenets of the much-touted American democratic project, which still paradoxically and sentimentally pronounces its embrace of an expansive freedom and equity before the lawnever mind our shared history of settlement, conquest, enclosure, enslavement, segregation, and ongoing dispossession. In Many Thousands Gone, Baldwins second major essay (an excerpt from which is included in this volume), he argues, The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. He reminds us that the story of this supposed ward of the nation is not very pretty since it conceals and contains so much of the history of our young republic, a violent tale that is revealed in symbols and signs, in hieroglyphics, and has thus necessitated a dangerous and reverberating silence. For too many, black people still haunt the national imagination in our postcivil rights climate of mass incarceration, state-sanctioned police violence, and a staggering wealth gap, as a series of shadows, self-created [...] which we now helplessly battle [...] a social and not a personal or a human problem; to think of [the black American] is to think of statistics, slums, rapes, injustices, remote violence.

This impoverished moral posture is what gives rise to the likes of a Donald J. Trump at what Baldwin might refer to as this very late hour in Americas racial career. But there he stood, vile and desperately illiterate, as one of two candidates vying for the highest office in the land, asking black people what it was, precisely, they had to lose in voting for him since their neighborhoods are riddled with violence, an alarming number of your men are unemployed, and your houses are obviously filthy. As black people are being shot in the street (as the corpses of your brothers and your sisters keep piling up around us, as Baldwin said in 1968), Trump (and so many others of his tribe) is naked in his contempt and disregard for black lives. There is something disorienting if not clinical that black folks are to be rendered so easily invisible and hypervisibleand always viewed in the aggregateon both the left and the right. This echoes Baldwins early and ongoing refusal of the easy and naturalized connection between black life and the social.

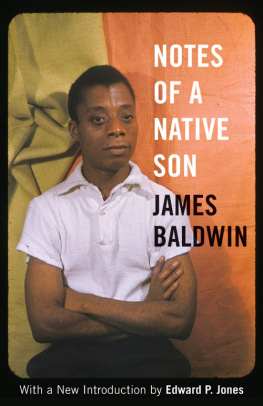

In this collection of selected poems and essays from Jimmys Blues and Notes of a Native Son, respectively, Baldwins words emerge less as prophecy concerning the ongoing racial nightmare in the United States and more like a secular gospel. James Baldwin, the little-boy preacher, left the church of his Harlem origins to spread the Word across the genres, to bear witness and testify to what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it, as he outlines in The Artists Struggle for Integrity. He is remembered as a prophet simply because he unflinchingly and courageously told the unvarnished truth about American life no matter the consequences. For, as he writes in Many Thousands Gone, it means something to be a Negro, after all, as it means something to have been born in Ireland or in China. [...] We cannot escape our origins.

Baldwins decades-long insistence that we confront the myths and legends that confirm the lie of the American dream resonates now because, as he maintained, citizens and the truth can only be suppressed for so long. If during election proceedings, black people persist in conjuring for politicians of all stripes, the rather unfortunate image of bones thrown to a pack of dogs sufficiently hungry to be dangerous, as he writes in Journey to Atlanta, then the visionary and love-filled movement for black lives that has emerged parallel to our countrys recent political theater is characterized by a hunger for a more complete and expansive picture of what it means to exist in relationship to white supremacy this long. For the generations of born-frees who opened their eyes on the Cape Flats or in Roxbury, the struggle is real, but their humanity is not in question. These young women and men are not easily catalogued in a roster of statistics or gazed upon as a living wonder, as Baldwin was in the Swiss Alps depicted in Stranger in the Village. And the reactionary or racist politicians remain mystified by their ever-growing presence. For as Baldwin lamented in Many Thousands Gone, Wherever the Negro face appears a tension is created, the tension of a silence filled with things unutterable. It is clear that although this is a tale no American is prepared to hear, it is beyond time to sound Gabriels horn again and truly examine what it means to exist as a Negro in America, which will necessarily teach us a great deal about ourselves.

The excerpts that follow offer an insightful and inevitably relevant introduction to the work of James Baldwin in two genres. The selections resonate now given his virtuosity as an essayist and, ultimately, what he fundamentally remainsa poet. But these writings also ring true given how much they still piercingly distill, with such clarity, wit, love and vulnerability, something of the story of the moral history of this country and its people. That moral pleas have done little to sway the politician or policeman never thwarted Baldwin. Here, we have his rare poetry, as well as a glimpse into the lasting concerns and preoccupations of one of the greatest essayists in modern literature at a time of spiritual and material anguish. At such periods his writings provide, for so many of us, more than a little sustenance for the journey.

Rich Blint

Staggerlee wonders

I always wonder

what they think the niggers are doing

while they, the pink and alabaster pragmatists,

are containing

Russia

and defining and re-defining and re-aligning

China,

nobly restraining themselves, meanwhile,

from blowing up that earth

which they have already

blasphemed into dung:

the gentle, wide-eyed, cheerful

ladies, and their men,

nostalgic for the noble cause of Vietnam,

nostalgic for noble causes,

aching, nobly, to wade through the blood of savages

ah!

Uncas shall never leave the reservation,

except to purchase whisky at the State Liquor Store.

The Panama Canal shall remain forever locked:

there is a way around every treaty.

We will turn the tides of the restless

Caribbean,

the sun will rise, and set

on our hotel balconies as we see fit.