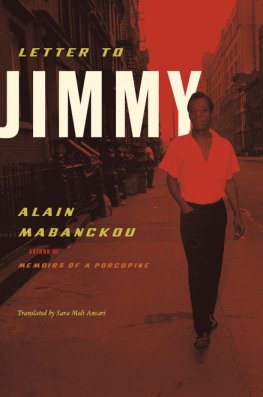

James Baldwin frequently changed or modified the title of a book while he was writing it. Go Tell It on the Mountain, for example, was previously Crying Holy and, before that, In My Fathers House; Giovannis Room was One for My Baby, then Backwater, and then something different; Another Country began life as that, changed to being The Only Pretty Ring Time, and changed back to Another Country again. Sometimes the title came to him first and the book would grow to fit it, and sometimes a title existed in his mind for a decade or more without a book being written for it. For a novel that he planned to set on Emancipation Day in 1863 on a Southern slave-holding plantation, Baldwin conjured the title Talking at the Gates. For almost twenty years, on and off, he talked about the book, but never wrote it.

Many people have shared their views and reminiscences with me in the writing of this account of Baldwins life and work. In the text, the statements of an interviewee are signified by use of the present tense, or by the introductory phrase According to ..., but seldom otherwise. Thus, John Brown says (etc.) or According to John Brown indicates that his remarks were made in an interview with me; but John Brown said (recalled, complained, etc.) means that the statement is taken from a book or an article, which the reader will find referenced in the notes.

As regards the sensitive issue of the words Negro, black, Afro-American, etc., I ought to say that I have in general followed Baldwin himself. After about 1972, the term Negro passed out of common usage, and it does so at roughly the same stage in this book.

This portrait of James Baldwin is offered not as a definitive picture but as a host of sketches and perceptions aiming toward a definition, yet finally backing down from one. No one, Baldwin used to say, can be described. In my view, it is more true of him than anyone.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful in particular to Vera Chalidze and Caryl Phillips for their consistent help and advice, and to many other people, including Ernest Allen of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Gidske Anderson, David Baldwin, Gloria Baldwin, Richard Baron, Ann Birstein, Mary Blumenau (ne Keen), Eugene Braun-Munk, Emile Capouya, Engin Cezzar, William Rossa Cole, Robert Cordier, Frank Corsaro, the staff of DeWitt Clinton High School, Fanny Dubes, Fern Marja Eckman, Michel Fabre, Eileen Finletter, Jamey Gambrell, Stanley Geist, Richard Gibson, Michael Greenberg, Lucien Happersberger, Bernard Hassell, Jim Haynes, Gordon Heath, Cathy Henderson of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research CenterUniversity of Texas at Austin, Kenton Keith, Yashar Kemal, Ann Kjellberg, Jim Lesar, Norman Mailer, Bertrand Mazodier, Sheila Murphy, Leonard Nelson, Richard Newman of the New York Public Library, Barbara Nordkvist, Zeynep Oral, Edward Parone, E.M. Passes, William Phillips and Partisan Review, Norman Podhoretz, Michael Raeburn, David Ross, William Shawn, Leslie Schenk, Jim Silberman, George Solomos (a.k.a. Themistocles Hoetis), Will Sulkin, Gulriz Sururi, Raleigh Trevelyan, Diana Trilling, Bosley Wilder, and Ellen Wright. I am also grateful to the Authors Foundation and to the US Information Service for generous assistance toward the costs of travel.

Publishers Acknowledgments

The publishers gratefully acknowledge permission to reprint copyright material:

The James Baldwin Estate for permission to quote the following: the poems Black Girl Shouting and To Her; the extract from the short story Peace on Earth; the extract from the directors notes for Fortune and Mens Eyes; the extract from Giovannis Room: A Screenplay. All this material remains copyright of the James Baldwin Estate.

Doubleday, New York, for permission to quote from the following works by James Baldwin: Go Tell It on the Mountain, copyright 1952, 1953 by James Baldwin; Nobody Knows My Name, copyright 1954, 1956, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, The James Baldwin Estate; Going to Meet the Man, copyright 1951, 1957, 1958, 1960, 1965 by James Baldwin; The Fire Next Time, copyright 1962, 1963 by James Baldwin; Blues for Mister Charlie, copyright 1964 by James Baldwin; No Name in the Street, copyright 1972 by James Baldwin; Tell Me How Long the Trains Been Gone, copyright 1968 by James Baldwin; If Beale Street Could Talk, copyright 1974 by James Baldwin; The Devil Finds Work, copyright 1976 by James Baldwin; Just Above My Head, copyright 1978, 1979 by James Baldwin.

Beacon Press, for permission to quote from Notes of a Native Son, copyright 1953, renewed 1955, by James Baldwin.

The lecture The Position of the Negro Artist and Intellectual in American Society by Richard Wright, copyright the Estate of Richard Wright.

The correspondence of Langston Hughes, copyright George Houston Bass, Surviving Executor of the Estate of Langston Hughes.

The diaries of Richard Burton, reprinted from Richard Burton: A Life 19251984 , by Melvyn Bragg, copyright 1988 by Sally Burton.

The Grave of Alice B. Toklas and Other Reports from the Past by Otto Friedrich, copyright 1989 by Otto Friedrich, published by Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

Introduction to the 2021 Edition

When I began the research for Talking at the Gates , in January 1988, the book-length bibliography on James Baldwin could be counted on the fingers of one hand. There was a short academic study by the Nigerian writer Stanley Macebuh (1973); two assortments of critical essaysin one case original, in the other gleaned from journals; a Twayne United States Authors volume; and a lively biography by Fern Marja Eckman that had its origins in a series of articles published in the New York Post in 1966. The mention of The Furious Passage of James Baldwin at the dinner table during my first visit to Baldwins home in St-Paul de Vence prompted eye-rolling on his part and a sardonic comment from his assistant Bernard Hassell, with the words Jimmys biographer held at arms length in invisible quotation marks. I recently reread it, however, and enjoyed again the up close, honest portrait it presents of a life lived at a dangerous pace in the mid-1960s. Shortly after Baldwins death, on November 30, 1987,Baldwin: Artist on Fire. It appeared in 1990, too late for me to make use of it. If there were other full-length treatments of Baldwins life and career before Talking at the Gates came out in Britain in January 1991 (April of that year in the United States), they have escaped my attention.