Also by William J. Maxwell

New Negro, Old Left:

African American Writing and Communism between the Wars (1999)

Claude McKay, Complete Poems (editor, 2004)

F. B. Eyes:

How J. Edgar Hoovers Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature (2015)

Copyright 2017 by William J. Maxwell

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First Edition

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maxwell, William J. (College teacher), author.

Title: James Baldwin : the FBI file / William J. Maxwell.

Description: New York : Arcade Publishing, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016058378 | ISBN 9781628727371 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Baldwin, James, 1924-1987. | African American

AuthorsBiography. | American literatureAfrican American

AuthorsHistory and criticism. | United States. Federal Bureau of

InvestigationHistory20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States /

20th Century. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | SOCIAL SCIENCE /

Ethnic Studies / African American Studies.

Classification: LCC PS3552.A45 Z822 2017 | DDC 818/.5409 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016058378

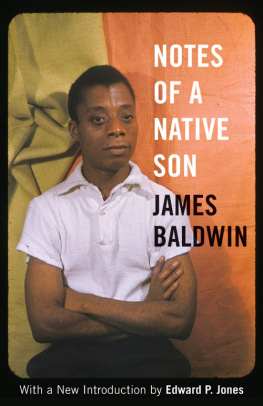

Cover design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Cover photo by Dave Pickoff: Associated Press

ISBN: 978-1-62872-737-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-738-8

Printed in China

CONTENTS

Introduction

BALDWIN AND HIS FILE AFTER BLACK LIVES MATTER

Born-Again Baldwin

James Baldwin, buried on December 8, 1987, often looks like todays most vital and most cherished new African American author. This impression doesnt rest on the faith in bodily resurrection that Baldwin abandoned along with his teenage ministry in Harlem. Nor does it slight Teju Cole, Natasha Trethewey, Kevin Young, and the rest of the emerging literary competitionthough its true that one leading light in that competition, Ta-Nehisi Coates, has suffered as well as profited from Toni Morrisons pronouncement that he fills the intellectual void opened by Baldwins passing. Instead, the impression that Baldwin has returned to preeminence, unbowed and unwrinkled, reflects his special ubiquity in the imagination of Black Lives Matter. As Eddie Glaude Jr. observes, Jimmy is everywhere in the advocacy and self-scrutiny of the young activists who bravely transformed the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Natasha McKenna, and far too many others into a sweeping national movement against police brutality and campus racism. For these activists, disruptive and creative and warning of new fires next time, Jimmy himself has filled the void traced to his death. Something like the Shakespeare of Stephen Dedalus, the Baldwin of Black Lives Matter is his own true fatherone who rehearsed for the role, its worth remembering, by raising several of his eight younger siblings and by peppering his live speech and written dialogue with the hip endearment of baby. With ironic paternalism, Baldwin habitually applied this sweet nothing to that set of permanent children proud of their whiteness. So I give you your problem back, he schooled a not especially fresh-faced interviewer in 1963, Youre the nigger, baby, it isnt me.

Its no state secret, of course, that Black Lives Matter, or BLM for short, is a movement fueled by electronic social media, by the graphic smartphone video followed by the mobile demonstration advertised on Facebook and choreographed in real time via Twitter. The thing about [Martin Luther] King or Ella Baker and the rest of the civil rights pantheon, explains DeRay Mckesson, the most prominent face of the movements techno-optimism, is that they could not just wake up and sit at breakfast and talk to a million people. The tools that we have to organize and resist are fundamentally different than whats existed before in black struggle. Regardless of the new advantages of instant mass communication, however, BLM has also begun to reorder the slow time of the African American literary canon like the Civil Rights Movement before it. Whatever BLMs cumulative political significance will bethe jury remains out amid white backlash, the election of backlasher-in-chief Donald Trump, the tragic assassination of police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge, and the slow fade of direct action as a defining BLM tacticit has already adopted more than one literary muse and has already stamped black literary history.

Considered as a generational sensibility indebted but not confined to the #BlackLivesMatter platform launched in 2013, BLM has embraced a lyrically withering essayist, the previously mentioned Coates, and has appointed an academic poet laureate, the National Book Award finalist Claudia Rankine. It has recuperated a militant memoirist, Assata Shakur, whose 1987 autobiography, written in Cuban exile, now rivals The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) as a passport to 1960s-style Black Nationalism. The medley of poetry, radical confession, selective legal history, and anti-racist name-taking in Assata an unexpected pre-echo of Rankines multigeneric collection Citizen (2014)has also yielded BLMs best-loved poem, a rewrite into rough ballad meter of the climax of The Communist Manifesto memorized and mass-chanted by thousands of protestors in dozens of American cities. It is our duty to fight for our freedom, Shakurs twice-historical lines direct,

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

Yet while Shakur is the author of BLMs If We Must Die, its street-tested anthem of unity-in-resistance, Baldwin reigns as the movements literary conscience, touchstone, and pinup, its go-to ideal of the writer in arms whose social witness only enhances his artfulness. Its Baldwins good name and impassioned queer fatherhood that aspiring movement intellectuals invoke in Twitter handles such as #SonofBaldwin, #Flames_Baldwin, and #BaemesBaldwin. Its Baldwins distilled racial wisdom, often mined from his heated Black Power-era interviews, that fortifies these intellectuals posts and tweets. (See, for instance, the viral social-media resharing of Baldwins correction of an Esquire magazine reporter in 1968: I object to the term looters because I wonder who is looting whom, baby.) Its Baldwins longer, formal prose thats recommended by BLM protesters for its uncanny relevance, its vintage elegance combined with the tight fit with present emergencies that, according to rapper-activist Ryan Dalton, says a lot about Baldwins writing, but also about how little progress weve made. Its the glossy black-and-white Library of America edition of Baldwins Collected Essays that rivals Assata Taught Me hoodies and DeRay Mckessons blue down vest as an iconic movement accessory. Its the second thoughts on Richard Wright and retaliatory violence in Baldwins essay Many Thousands Gone that Rankine samples in detail in the World Cup section of Citizen . And its The Fire Next Time (1963), Baldwins unforgettable but often misremembered meditation on the Islam of Elijah Muhammad and the Christianity of and against Martin Luther King, that underwrites the whole of Coatess Between the World and Me (2015), on whose dust jacket Toni Morrison declares the author the most gifted Son of Baldwin of all. Coates is happy to admit his bestsellers steep debt to the older writer; the influence became inevitable, he tells us, after he reread The Fire Next Time and asked himself why dont people write short, powerful books like this [anymore], a singular, hundred-page essay? One reason why more people dont, its fair to say, is that Baldwin is now, practically speaking, back among us to write such books on his own.