My European Family

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p53: The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms Under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

Chilled by Tom Jackson

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

To Anita and Gran, from whom I inherited all my genes.

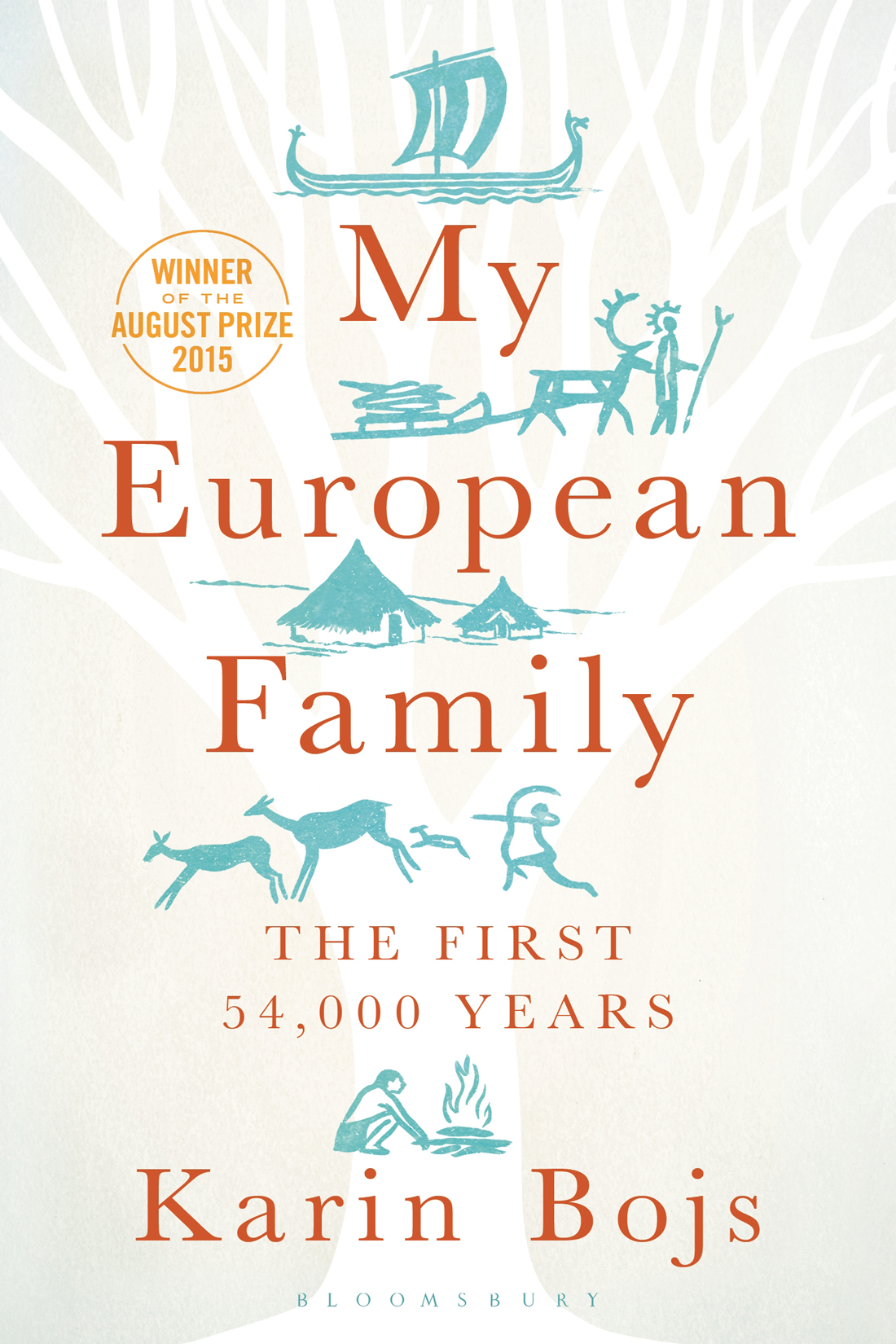

My European Family

The FIRST 54,000 years

Karin Bojs

Contents

My mother, Anita Bojs, died while I was working on this book. Many friends and acquaintances came to the funeral, considerably more than I had dared to hope for. But there were only a few family members. All of us fitted into one pew at the front: my brother and me, our partners, and three smartly dressed grandchildren.

It was early summer, and the mauve lilac was in bloom in the park next to Gothenburgs Vasa Church. Together we sang the hymn Den blomstertid nu kommer (The blossom time is coming), followed by Hrlig r jorden (Fair is Creation). I had chosen the latter because it includes two lines that I find particularly comforting: Ages come and ages pass / Generation follows upon generation.

When the time came for the memorial speeches, I addressed myself particularly to Anitas grandchildren. I wanted them to feel proud of their grandmother and her origins, despite the circumstances.

The grandmother they had known was elderly and scarred by life. Her promising career had come to an end when she was still in her fifties. By then she already had a long history of serious problems including illness, divorce, conflicts and addiction.

That was why I told her grandchildren and the other people at the funeral about the first half of my mothers life. I told them about the student who scored top marks at school and landed a place to study medicine at the Karolinska Institute although she was a girl and came from a family of modest means. I told them about her childhood home above the little school in the industrial village where my grandmother Berta taught. That home had been poor in financial terms, but it was all the richer in companionship, music, art, literature and the thirst for knowledge.

I quoted from a diary I had found among my mothers things. Top Secret was written on the cover in a childish hand. In the diary she had written about her summer holidays in the province of Vrmland, at the home of her grandmother, my great-grandmother Karolina Turesson. It was just 40 kilometres (25 miles) away from the border with Norway, where the Second World War was raging. Yet the description of the cousins playing together on the jetty at glittering Lake Vrmeln was so bright and full of beauty in retrospect.

I never met my maternal grandmother or great-grandmother. With all the problems there were in my troubled family, I seldom met any relatives at all. That may be why I have spent so much time wondering who these relatives were and where they came from. I have wanted to know more since I was a 10-year-old.

On my fathers side, at least I met my grandmother Hilda and my grandfather Eric a few times. My visits to them are among my happiest memories. Their home in Kalmar smelt so good. There were paintings everywhere, and my grandfather had decorated doors, walls and furniture with pictures of his own. Both grandparents were fond of telling stories from their childhood, but they rarely said anything about family further back in the past.

Now, as an adult, expert genealogists have helped me to trace Bertas, Hildas and Erics ancestry over many generations. When I was young, I thought it was rather nerdy to research your family history. But as an adult I now have far more respect for the activity. I understand how a fascination with ones forebears is an important component of many of the worlds cultures. In many of the ethnic groups that lack a written tradition, people can rattle off their ancestry for at least 10 generations about as far back as successful family history researchers in Sweden. The Bible sets out lengthy genealogies, the oldest of which were written down over 2,000 years ago, having being passed on by oral tradition long before that.

Methods for tracing ones ancestry have moved on since biblical times. In fact, I would say the current unprecedented developments are nothing less than quantum leaps. About 50 years ago, a few pioneering researchers began to compare blood groups and individual genetic markers in order to be able to identify family connections and historical migrations. At that time, the DNA molecule had only been known for a few years, and the relevant knowledge was shared by a very limited group of researchers. It was not until 1995 that it became possible to examine all the DNA of a tiny bacterium. Since then, progress has been astonishingly rapid. In fact, biotechnology is undergoing even more dramatic developments than information technology, although advances in computing, telephones and the internet are more visible to the general public. IT people speak of Moores law, according to which computers double their capacity every two years. The capacity to map a DNA sequence is advancing much faster than that.

A few years ago, it became possible to analyse the whole of a persons genetic make-up in a matter of hours. Researchers can even analyse DNA from people who have been dead for tens of thousands and, in one or two cases, hundreds of thousands of years. An analysis that would have cost tens of millions of pounds a decade or two ago is now obtainable for less than 50. Thanks to lower prices, this technology has also begun to spread beyond the world of professional research. Even private individuals researching their family tree have started to use DNA as a tool. Small variations in the DNA sequence make it possible to identify unknown first, second and third cousins, and even family members who lived a very long time ago during the last Ice Age and even further back.

I have followed developments in DNA technology as a science journalist over the last 18 years, for most of which I have been science editor at Dagens Nyheter , one of Swedens leading daily newspapers. I have witnessed a revolution in the technology used in criminology and medical and biological research, and I have seen how DNA technology is now beginning to contribute to archaeology and history as well.

This book is an attempt to gather together these different threads: professional researchers latest findings about the early history of Europe, and my own particular family history. My research has involved travelling in 10 countries, reading several hundred scientific studies and interviewing some 70 researchers.

I am now beginning to be able to discern the threads that link my maternal great-grandmother Karolina, my paternal grandmother Hilda and my paternal grandfather Eric, and events that took place a long way back in history. Most of these threads are shared with a large part of the population of Europe.