PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2016 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

The parcel / Anosh Irani.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

I. Title.

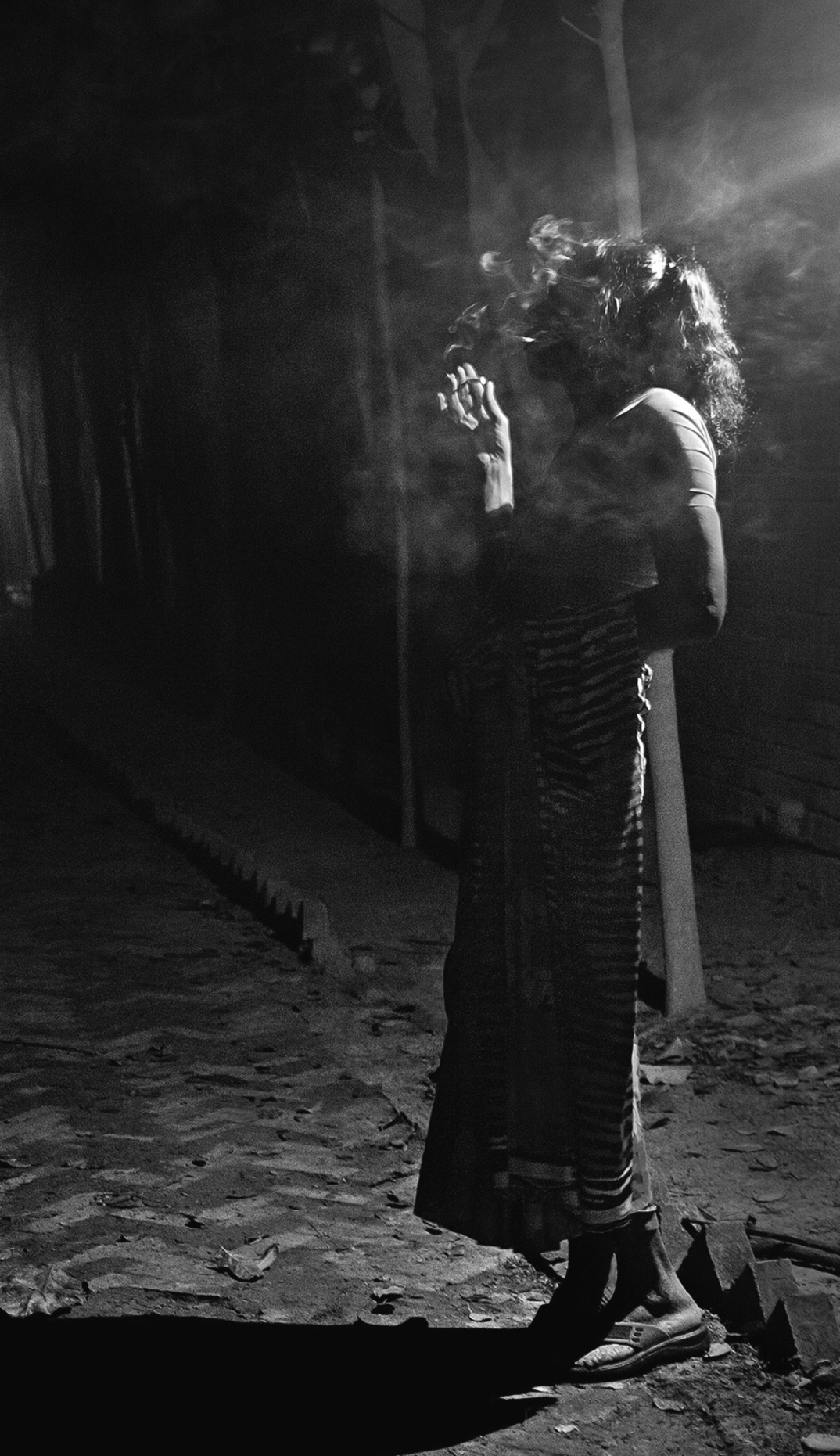

Cover images: (Doves and cages) Katie Edwards / Ikon Images / Getty Images; (old taped paper) David M. Schrader, (floral background) Steven Bourelle, both Dreamstime.com Interior image: Shahria Sharmin

Prologue

I go by many names, none of my own choosing.

I am called Ali, Aravani, Nau Number, Sixer, Mamu, Gandu, Napunsak, Kinnar, Kojjathe list goes on and on like a politicians promise. There is a term for me in almost every Indian language. I am reviled and revered, deemed to have been blessed, and cursed, with sacred powers. Parents think of me as a kidnapper, shopkeepers as a lucky charm, and married couples as a fertility expert. To passengers in taxis, I am but a nuisance. I am shooed away like a crow.

Everyone has their version of what I am. Or what they want me to be.

My least favourite is what they call my kind in Tamil: Thirunangai.

Mister Woman.

Oddly, the only ones to get it right were my parents. They named their boy Madhu. A name so gloriously unisex, I slipped in and out of its skin until I was fourteen. But then, in one fine stroke, that thing between my legs was relieved of its duties. With the very knife that I hold in my hand right now, I became a eunuch.

Perhaps my parents had smelled the strangeness in the air when I was born, the stench of the pain and humiliation to follow. At the least, they must have felt a deep stirring in the marrow of their bones to prepare them for the fact that their child was different.

Neither here nor there, neither desert nor forest, neither earth nor sky, neither man nor woman.

The calling of names I made my peace with years ago.

The one I am most comfortable with, the most accurate of them, is also the most common: hijra. The word is Urdu for migration, and we hijras have made it our own because its meaning makes sense to us.

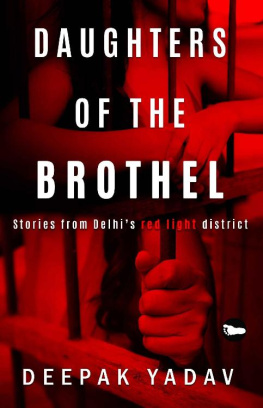

I am indeed a migrant, a wanderer. For almost three decades, I have floated through the citys red-light district like a ghost. But this home of mine, this garden of rejectsfourteen lanes that for the rest of the city do not existI want it to remember me. I want it to remember even though the district is dissolving, just like I am, like the hot vapour of chai.

Come on. Who am I fooling? I dont taste like chai. I am anything but delectable. I have been born and brewed to mortify. At forty, all I have left is a knife dipped in the moon and a five-rupee coin given to me by my mother.

But mark my words: I will make myself a household name. I will spread my name like butter on these battered streets.

1

U nderwear Tree had its name thanks to the array of underclothes that were left to hang and dry in its loving care. It was one giant hanger for clothes, a dhobis delight. At any time of day, underwear in all shapes and sizes were caught in its branches like kites. Over the years, Underwear Tree served as a barometer for economic growth. If the elastic of the underwear was tight, it signified that the people living in the hutments below the tree were doing well. If the elastic was loose, it meant overuse for the underwear and hard days for the owners.

As Madhu looked up, she could see that the underwear that lay stiff in the morning sun was somewhere in between. Things could go either way from here. She, on the other hand, had only one place to go: Bombay Central for her daily bread and butter, and an array of abuses. But before going to work, she, as always, called upon that brave Maratha warrior Shivaji to kick-start her day as she inhaled his majestic beedis.

She sent the smoke skyward, toward the pride of her neighbourhood, until she tasted the last bitter hit. That final trace of tobacco surging through her brain was what she enjoyed the most. Before flicking the beedi away, she burned a hole in the fabric of her sari with the lit end.

It was a habit to rid her of anxiety; she also did it for luck.

She smiled as the beedi disappeared into a gutter. Even dead cigarettes wanted to get away from her as soon as possible.

No shirt, no pants, no tie, but she was an office-goer like any other Mumbaikar. Her working space was in the most prime location. Bombay Central was her terrain, and she had worked it more than any other hijra in the city. It was her designated area. Only a few hijras, from her clan, had the right to beg here. Any infringement from an outside hijra. and Madhu would push a bamboo up her arse so deep, if she were to lift the bamboo to the sky it would become a flaga trespassing hijra in a flowing sari hoisted among the clouds, singing in pain.

How she wished she had the strength to do that.

At forty, she was weak, her muscles looser than they had ever been, her belly resembling a hot-water bag, bulgy and changing shape without warning. The only thing she was capable of lifting was her middle finger. She showed it to passengers in cabs every single day.

Only in her mind.

She had to respect the passengers. They were allowed to abuse her, but she could not abuse back. That was a hijra rule.