Madhu Ramnath - Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People

Here you can read online Madhu Ramnath - Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: HarperLitmus, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperLitmus

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Madhu Ramnath: author's other books

Who wrote Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Woodsmoke

and

Leafcups

Autobiographical footnotes to the anthropology of the Durwa people

MADHU RAMNATH

To the women in my life, both past and present.

Oh whats become of the world, Zaabalawi?

Theyve turned it upside down and taken away its taste.

Naguib Mahfouz, The Time and the Place, First Anchor Books, New York, 1992.

CONTENTS

Powerful, elegant and important this is a book that takes us to the daily life, the intimate preoccupations and the most urgent challenges deep in the forests of Bastar, in the very heartland of an Adivasi world. In these beautifully written, poignant and compelling narratives, Madhu Ramnath shares with us his own immersion in that world. He writes with remarkable lightness of touch, with great humour and compassion; yet reveals an encyclopaedic knowledge and understanding of both the natural and social world to which he leads us. The book reveals both what it can mean to be human, and how much of humanity is at terrible risk.

In these wonderful stories, the careful balances of Adivasi life are shown again and again to be at the mercy of the powerful and the corrupt representatives of an alien and dominant state. Here is a book to delight in, be inspired by and learn from. Every part of it sends out a vital message. In the stories, rituals, songs and everyday realities of the peoples who have lived since time immemorial on their lands in those forests, in all that Ramnath has experienced and now describes, may lie much that humanity both yearns for and needs. And that could all too easily be lost. So much of life in the forests we enter is rich with meaning and beauty and laughter; all of this is at risk.

This is a book for everyone who seeks to know the world, for anyone who cares about the heartlands of humanity, and for all who would wish the world to save itself from mindless and destructive indifference to both the forests and the people who know the forest best. It cries out to be read by us all. All who read it will be enchanted.

Hugh Brody

Anthropologist, writer, lecturer

No better love than love with no object,

No more satisfying work than work with no purpose,

If you could give up tricks and cleverness,

That would be the cleverest trick.

Jalaluddin Rumi, Rumi: Selected Poems, translated by Coleman Banks, Penguin, 1995.

The beginning

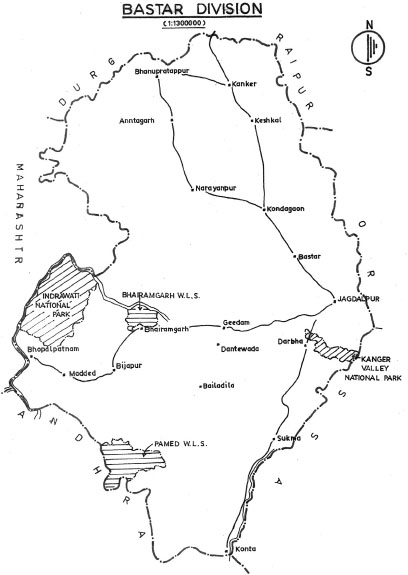

O ne summer, about thirty years ago, I spread a map of India on the floor of my room at university. A large swathe of the country in central India was conspicuous for the paucity of roads criss-crossing it. Delighted with this discovery, I decided to go and explore that part of India, spread across a large area of erstwhile Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and Maharashtra. Little did I then realize that Id embarked on a journey that would span several decades; one that would transform the way I saw myself, and provide me with another vantage and perspective from which to view the world.

My first trek began from a small town called Bijapur, the outskirts of which merged with the forest, from where I drifted roughly south for about two weeks towards Bhadrachalam. Along the way, I met and lived with Adivasi people principally Dorla and Dandami Maria who took care of me, giving me my first glimpse of how life could be lived. Clearly, Id been seriously off the mark.

Brief stints in the forests fed a desire to remain there. As soon as I was through with college, buoyed by youthful exuberance and impatience, I turned my back on both university and city and headed for Bastar. I found shelter and a vocation in one of the hill villages that bordered Orissa and, among other things, took a keen interest in plant identification. I spent my youth exposed to pleasures and pain of a kind that confirmed something I couldnt lay my finger on. Bastar remained outside the country I knew and with which I was familiar: the scent of sal hinting at something more refreshing than the goals to which India aspired. As Lucretius remarked of early mankind, everything was new and marvellous. Energy and laughter were the currencies of this new land, and the beat of a drum its pulse. Not many recognized the worth and genuineness of these currencies, tested by time and lamented that the Adivasi continued to be a race that had no use for the copper coin. I became a student of Adivasi life; the village and the forest became a place of learning, everyone I met a teacher.

The contents of this book have been gleaned from the notes I maintained over the past thirty years, supplemented by memory. The latter plays tricks, alters perspectives of events over time, but what seemed important then I continue to hold to be important today, in a world becoming increasingly cramped and one in which there are few places in which to lose oneself.

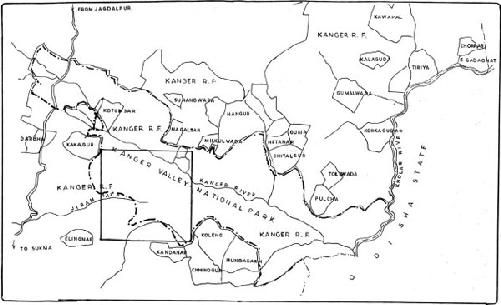

The landscape

The greater part of Bastar is a tilted peninsular plateau, varying in elevation between 284 and 1,200 m. Uninterrupted denudation over millions of years has grievously dissected this plateau of ancient crystalline rocks marked by river valleys and flood plains with relict uplands, hills and mountains. The principal rivers of the region are Indravati and Sabari, both tributaries of the Godavari in the south, the largest of the rivers flowing west to east in the region. Winter nights can be extremely cold and most Adivasi homes get by with a fire to sleep beside. Summer is hot, sometimes sufficiently so to cause stands of sal trees to dry up and die.

A way of life

I maintained, to the best of my ability, a Durwa lifestyle over many years. A preoccupation with plants came early, with most conversations, even casual ones, such as indicating direction in the forest, entailing some reference to them. Moving around the forest with my companions made clear the advantages of being unshod and minimally clad; it was imperative that I be an asset and not a burden in a food-collection expedition if I wanted to be part of it. Fishing, gathering and hunting excursions were learning experiences as much as a way of life. Coming from a softer society, where money smoothed most paths, I struggled and stumbled through my lessons for some years until the pursuit paid off, the body as well as the mind adapting to what was present and immediate.

Land and people

Most agriculture is rain-fed, depending upon the south-west monsoon. July and August are the wettest months, accounting for over three-fourths of the seasons rain. People get their ploughs and spades ready and mend their fences when the nowdeli begins to bloom; harvest nears completion by the time the large nephila spiders weave their orbs across forest trails; when wild boar begin to dig up the roots of thummi plants. A season of festivity then commences, through a brief spring and into a long summer. People travel to meet relatives and friends, to marriages and fairs, to chutoks and annual offerings at the village shrines. Many of the journeys are on foot, sometimes with a night en route, each a pilgrimage and a tale in itself.

However, important as agriculture is, it is the range of wild foods that people consume which endows them with their independent disposition. There are over 500 species of plants and animals that the Adivasi procure and judiciously manage. In villages at a distance from the roads, where sizeable forests continue to thrive, the people are healthier than their relatives who live in the proximity of towns. Until the late 1980s, stitched cloth did not exist in most villages; most men wore a simple loincloth that sufficed to enable them to conduct the daily business of life. On formal occasions, a longer and wider piece of cloth was worn that could be wrapped around like a skirt, with a tail sticking out. A womans luga was barely more than five hands long, wrapped essentially around the waist and above the knee, stylishly knotted at one shoulder; it did not hinder her climbing a tree or springing across a stream. A societys self-reliance is usually in inverse proportion to its reverence for the state. In some inexplicable way, the Adivasi of the deep forest showed his disdain for the sahib by wearing less; the threshold of shame increased as one neared the towns where he showed less of himself.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People»

Look at similar books to Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical Footnotes to the Anthropology of the Durwa People and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.