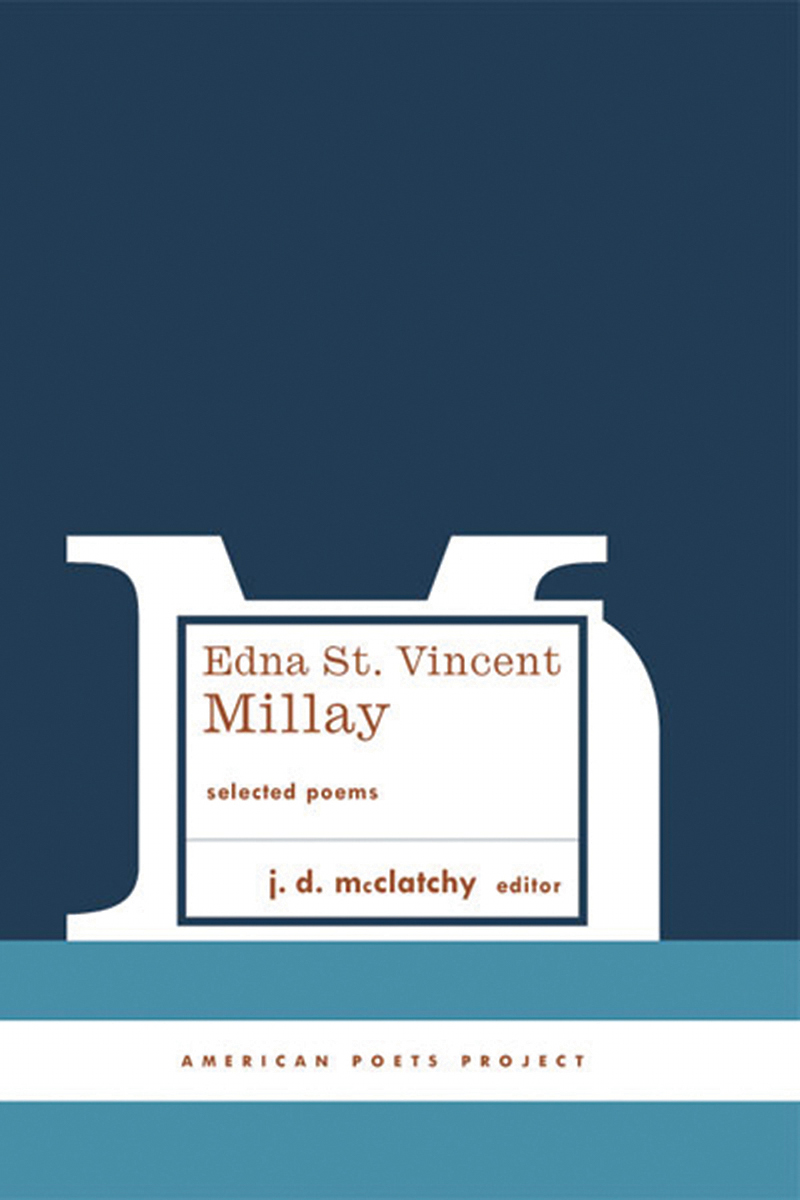

AMERICAN POETS PROJECT

The American Poets Project is published with a gift in memory of JAMES MERRILL

AMERICAN POETS PROJECT

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America's best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by America's foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen. If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will

never share your e-mail address). Introduction, volume compilation, and notes copyright 2003 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. No part of the book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission. The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems copyright 1923 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1951 by Norma Millay Ellis. The Kings Henchman copyright 1927 by Edna St. The Buck in the Snow copyright 1928 by Edna St. The Buck in the Snow copyright 1928 by Edna St.

Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1955 by Norma Millay Ellis. Fatal Interview copyright 1931 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1958 by Norma Millay Ellis. Wine from These Grapes copyright 1934 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1962 by Norma Millay Ellis. Flowers of Evil by Charles Baudelaire, copyright 1936 by Edna St.

Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1963 by Norma Millay Ellis. Conversation at Midnight copyright 1937 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1964 by Norma Millay Ellis. Huntsman, What Quarry? copyright 1939 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1967 by Norma Millay Ellis. Make Bright the Arrows copyright 1940 by Edna St.

Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1968 by Norma Millay Ellis. The Murder of Lidice copyright 1942 by Edna St. Vincent Millay, copyright renewed 1969 by Norma Millay Ellis. Mine the Harvest copyright 1954, copyright renewed 1982 by Norma Millay Ellis. Reprinted by permission of The Edna St. Vincent Millay Society.

Design by Chip Kidd and Mark Melnick. Frontispiece photo by Berenice Abbott. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data (Print): Millay, Edna St. Vincent, 18921950 [Poems. Selections] Selected poems / Edna St. Vincent Millay ; J.D.

McClatchy, editor p. cm. (American poets project ; 1) Includes index. ISBN 1931082359 (alk. paper) I. Title: Edna St.

Vincent Millay. II. McClatchy, J.D., 1945- III. Title. IV. Series PS3525.I495 A6 2003 811.52 dc2 2002032126

INTRODUCTION

If literary historians can agree on anything, its that the road to hell is often paved with good reviews.

At the start of her career, Edna St. Vincent Millays reviews were astonishing. By 1912, when she was just eighteen, she was already famous. When, five years later, her first book appeared, she was launched on a rushing current of acclaim. If by the end of her life most of the good reviews were merely dutiful, for the run of years in betweenduring the tumultuous decades of the 20s and 30s, in a world between wars, at first jazzed and roaring, later impoverished and threatenedher readers and critics clung to her celebrity and swooned over her poems. E. E.

Housman praised her virtuosity. Thomas Hardy once famously said that the two great things about America were its skyscrapers and the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay. In 1952, two years after her death, when it was already unfashionable to admire Millay, her devoted reader and one-time lover Edmund Wilson insisted that Edna Millay seems to me one of the only poets writing in English in our time who have attained to anything like the stature of the great literary figures. But that was the last time such a claim was made. By 1976, she was not even represented in The New Oxford Book of American Verse. The sand had all run through the hourglass.

How changed everything was from the beginning, when Millay, still a student at Vassar, first dazzled Manhattans literary salons. She looked like a candle: small, intense, pale, with hair the color of fire. And in a voice surprisingly deep and exquisitely controlled, she would read her latest poem. Louis Untermeyer was there and remembered that there was no other voice like hers in America. It was the sound of the ax on fresh wood. So what happened? Millay herself, in a letter, once blamed the decline of her reputation on her political activism.

In fact, she had eloquently championed Sacco and Vanzetti in 1927, and a decade later vigorously campaigned against American isolationism. And throughout her career she was an ardent feminist. All this made her a prominent target for the disapproval of some. Though her propaganda work during the war taxed her always fragile health and neurotic temperament, and she herself realized that her poems of this period were inferior to her best, this can hardly have been the only reason for the decline in her critical stature. It is more likely that the alcohol and drug addiction that plagued the last fifteen years of her life drained her powers of concentration, though her posthumous collection, Mine the Harvest, contains poems as fleetingly spirited as before. S. S.

Eliots Modernism, Inc. In a 1937 essay, for instance, John Crowe Ransom described Millay as the best of the poets who are popular and loved by Circles, Leagues, Lyceums, and Round Tables, and went on to complain that she is fixed in her famous attitudes, and is indifferent to intellectuality. He says that because, after all, a woman lives for love, and man distinguishes himself from woman by intellect. This defines her limitation: If I must express it in a word, I feel still obliged to say it is her lack of intellectual interest. It is that which the male reader misses in her poetry, even though he may acknowledge the authenticity of the interest which is there. I used a conventional symbol, which I hope was not objectionable, when I phrased this lack of hers: deficiency in masculinity.

Opinions like that nearly take the breath away now, but in fact Ransoms kind of venomous condescension has echoed down the years. The terms of contempt may have shifted, but the intention has been constant: to ridicule Millays haplessly old-fashioned manner and the shallowness of her sensibility. The fact that, during this same time, young readers, especially women, kept making their secret discoveries of Millays sway over their hearts mattered little. Critical opinion had blown out the flame. It is an odd irony that her detractors, even today, dismiss her work as sentimental, cloying, fusty. In their day, of course, her poems startled readers with their edgy candor, their fearless passion, their silvery structures.

This only points up the shifting tides of cultural assumptions, and should serve to remind us how incautious have been more recent evaluations of her achievement. Take as an example one of her earliest and best-known sonnets: If I should learn, in some quite casual way, That you were gone, not to return again Read from the back-page of a paper, say, Held by a neighbor in a subway train, How at the corner of this avenue And such a street (so are the papers filled) A hurrying man, who happened to be you, At noon today had happened to be killed I should not cry aloudI could not cry Aloud, or wring my hands in such a place I should but watch the station lights rush by With a more careful interest on my face; Or raise my eyes and read with greater care Where to store furs and how to treat the hair. The poem was published in 1917, as part of her first book,

Next page