IN SEARCH OF

CHOPIN

Alfred Cortot

Translated by

Cyril and Rena Clarke

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Peter Nevill Limited, London and New York, in 1951.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-49107-3

ISBN-10: 0-486-49107-2

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49107201

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS

Chapter

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Height five feet seven inches, a round chin, an oval face, a medium-sized mouth. These details are contained in a passport issued to Chopin in Paris on 7th July, 1837. In this same document his parentage is stated to be French. He had accompanied Camile Pleyel on a short visit to England during that year. A passport was a necessity; red tape was as abundant then as now, hence the false statement concerning his parents.

If one accepts as accurate the only precise information given in this casual official description, he was slightly below normal height.

For all who came near him his appearance was characterised by an indefinable resilience. A deceptive impression, engendered perhaps by the fact that his weight was well below average. In 1840 it was ninety-seven pounds, just under seven stone.

As if to defend herself from the whirlpool of gossip that would attend the first sign of any cooling off in her notorious liaison with the composer, George Sand confirms this impression for us. In her provocative novel, Lucrezia Floriani , she sketches Chopin in the guise of Prince Carol. Delicate in mind as in spirit, his face has the beauty of a sad woman. Careful to omit no detail that will fix the identity of her model, she adds, pure and slender of form as a young god from Olympus and to crown the whole, an expression at once tender and severe, chaste and passionate.

Liszt gives an equally poetic description of the personality of this man, whose genius was to inspire some pages of remarkable aesthetic insight. His appearance formed a harmonious whole his blue eyes were more spiritual than dreamy, his gentle, delicate smile held no trace of bitterness. The fineness and transparency of his complexion bewitched the eye, his fair hair was silky, his carriage distinguished, his manners so instinctively aristocratic that everyone treated him as though he were a prince. His gestures were full of grace and freedom, the tone of his voice was muffled to the point of being stifled.

It is apparent that Chopins contemporaries were incapable of remaining on the level of material reality when speaking of him. Liszt continues, His whole appearance reminds one of the unbelievable delicacy of a convolvulus blossom poised on its stema cup divinely coloured but so fragile that the slightest touch will tear it.

Charles Legouv carried away from their first meeting the impression that he had just encountered such a son as Weber might have fathered had the mother been a Duchess.

Finally there is this appreciation by Moscheles:

What is Chopin like to look at?

His music.

In spite of its abruptness, it is not far from being the most penetrating and suggestive description we have of the poet of the Nocturnes.

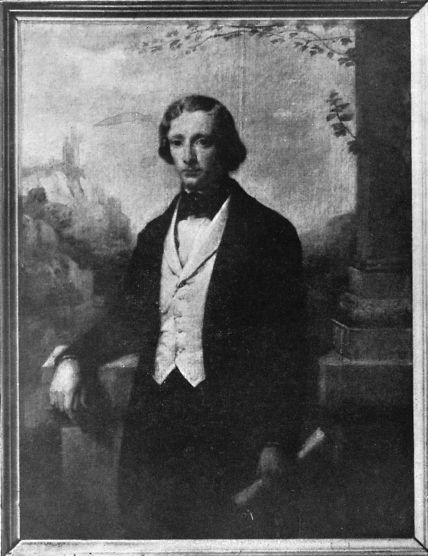

Diligent research, and an occasional unexpected piece of luck, have enabled me to acquire several interesting portraits of the composer. The artists brush confirms the writers attempts to describe an incomparable art.

In the sentences that follow, it is my intention to compare these portraits with the prose sketches I have quoted. The writers unanimity of opinion bears the hallmark of truth. It is in no way augmented by the addition of the writings of Delacroix, Heine or Berlioz, which do little to bring him more clearly to life.

I hope that the description of these pictures, so far unknown or ignored, may add to the small body of material available for us to draw upon in the documentation of Chopins outward appearance, and help towards a more intimate approach to his personality.

In the portrait that was once in the possession of the historian, Charles de Mazade, before coming to me, Chopin wears the expression George Sand describes when she picks out his essential characteristics.

Emaciated, melancholy rather than sorrowful, the delicate features bear the marks of a relentless disease.

His eyes, more grey than blue, eyes which, we are told, could fill with laughter over childish pranks, look rather set and distant as though clouded over with the film of fever.

The mouth and chin remain those of a boy, the lips bloodless, and the shape of the chin indicates an almost feminine fragility.

Only a proud Bourbon nose, the object of so many jokes on his part, a feature which in anyone else might have been considered sensual, defies the menacing symptoms of his illness and gives some indication of his burning vitality.

With a quite unexpected realism it contradicts the immateriality of his character, which is shown so clearly in his pensive likeness. One might almost say it is prophetic of the ghost destined to remain a legend for all time.

Less dramatic than the stormy Delacroix in the Louvre, but with a more intense expression than the elegiac Ary Scheffer, of which only the Dordrecht copy now exists, lacking the impersonal rigidity of the Kolberg in the Warsaw Museum, this picture shews him to be just such a person as his music would lead one to imagine him to be. In feeling it comes very close to the tenderness which his brief and sad existence inspires in usa feeling halfway between an irresistible need for confidence and an instinctive shrinking from disillusion.

So far, all my efforts to identify the artist with the necessary guarantees of authenticity have been in vain. Personally, I think it is permissible to attribute it to the Italian painter, Luigi Rubio.

In a lithograph of the pianist, Gottschalk, and in a portrait of Franchomme at the age of six, perched on the end of a grand piano with his violin, the Princess Czartoryska, that great and faithful friend of Chopin, at the keyboard, Rubio employs a technique undeniably similar to that used in the painting to which I refer.

Other reasons, which follow, also seem to justify my supposition.

A young pianist, whose name, Vera de Kologrivoff, leads one to assume that she was of Russian extraction, was Chopins pupil and later an assistant tutor for some of his aristocratic students. From 1842 to 1846 she was constantly in his society. She became, until Mlle de Rozires felt herself called upon to supplant her in this role, the involuntary recipient of his more intimate confidences. She was probably the first to be aware of the uneasiness which began to creep into his relationship with George Sand, an uneasiness which, in the face of daily shocks of disillusionment, was not long in reaching an irreparable break between these two victims of misplaced affection.

In a letter to Chopin, dated 1843, she informs him that she has spoken to M. Rubio about a portrait. To save Chopin the effort of climbing stairs, Rubio has for this once consented to depart from his normal practice and come to him with his palette and brushes. Rubio is determined, she adds, to finish the little portrait in oils in two sittings. She ends by begging Chopin to agree to the project because she wishes there to be in existence a portrait that is a likeness. Since three years later she became the wife of the young painter, her prejudice in favour of Rubios talents was, no doubt, due to considerations other than those of a purely aesthetic nature.

Next page