CIVIL IMAGINATION

A Political Ontology

of Photography

ARIELLA AZOULAY

Translated by

Louise Bethlehem

This paperback edition first published by Verso 2015

First published in the English language by Verso 2012

Translation Louise Bethlehem 2012, 2015

First published as

[Civil Imagination: Political Ontology of Photography]

Resling Publishing, Israel 2010

All rights reserved

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted

to reproduce the images in this book. Every effort has been made to trace

copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright

material. The publisher apologizes for any omissions and would be grateful

if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-303-7

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-302-0 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-301-3 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress Has Cataloged the Hardcover Edition as Follows:

Azoulay, Ariella.

[Dimyon ezrahi. English]

Civil imagination : a political ontology of photography / Ariella Azoulay; translated by Louise Bethlehem.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-84467-753-5

1. Photographic criticismIsrael. 2. PhotographyPolitical aspectsIsrael. 3. PhotographyPhilosophy. I. Title.

TR187.A98313 2012

770.1dc23

2012006239

Typeset in Sabon by Hewer UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Press

CONTENTS

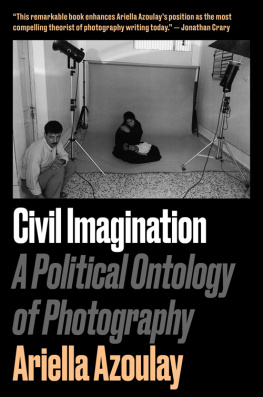

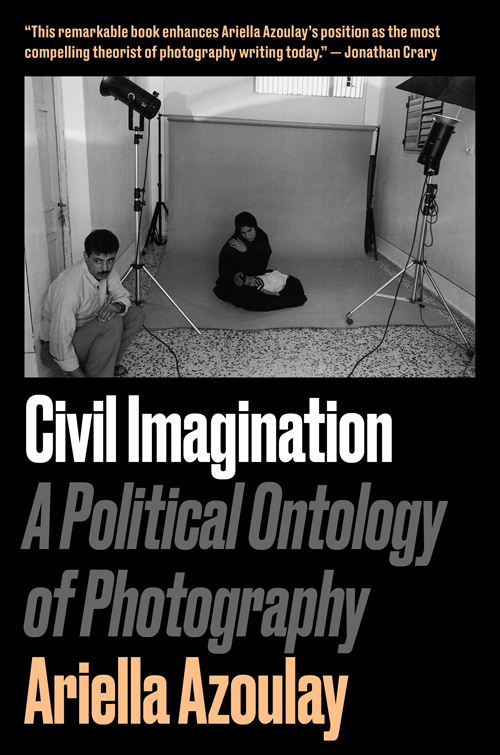

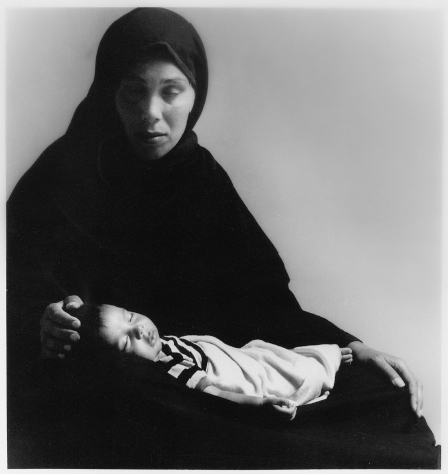

Cover: Micha Kirshner, preparations for photographing Aisha al-Kurd and her son Yassir, 1988

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Epilogue

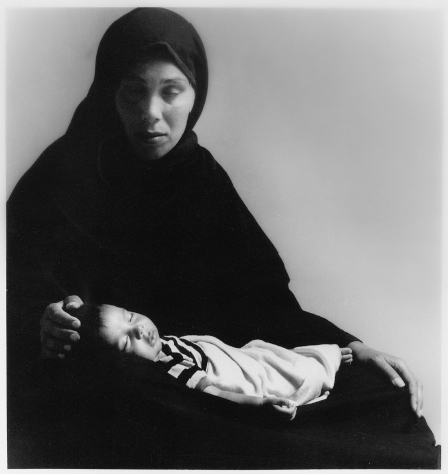

Micha Kirshner, Aisha al-Kurd and her son Yassir, 1988

The woman whose portrait appears on the opposite page, Aisha al-Kurd, is the overt and covert interlocutor of this book. I have never met her in person. Yet she has accompanied my thought ever since I first saw her photograph. Aisha and her husband (whose name I do not know), the parents of five children, were held in administrative detention for months by the Israeli authorities in 1988, and their house was demolished. When I first encountered her portrait during the late 1980s, I mistakenly viewed it as an instance of the aestheticization of suffering: the creative output of photographer Micha Kirshner. At the time, I thought that my analytical position concerning the aestheticization of suffering was a critical one. It was only later that I became aware of the trap inherent in such a stand. This trapwhich routinely opposes the aesthetic to the politicalalready preoccupied me at the time, but it was only gradually that its features, as well as the worldview that it organizes, became clear to me. The present volume will explore the fallacy that beset me then at length, while simultaneously attempting to rethink the category of the politicalits boundaries and limitationsas well as to clear space for the emergence of a different categorythat of the civil.

My encounters with Aisha al-Kurd over the years, meetings that exist only under the cover of the imagination, reflect changes in my thought concerning photography, concerning the sphere of the political, and concerning citizenship. On the basis of her photograph, and photographs of other individuals, this book seeks to imagine a civil discourse under conditions of regime-made disaster. Under such conditions, citizenship is restricted to a series of privileges that only a portion of the governed population enjoys and, even then, to an unequal degree. The central right pertaining to the privileged segment of the population consists in the right to view disasterto be its spectator. What is at stake is not the enjoyment that potentially attaches to the act of spectatorship, but the act itself, which is reserved for the privileged bearers of citizens rights who are able to observe the disaster from comparative safety, whereas those whom they observe belong to a different category of the governed, that is to say, people who can have disaster inflicted upon them and who can then be viewed subsisting in their state of disaster.

The scandal that attaches to the portrait of Aisha al-Kurd does not reside in the photograph itself, whether in its aesthetic value (its beauty seems to transcend disputes of taste) or in any other of its discrete qualities. The scandal lies in the fact that Aisha al-Kurds house was, and remains, vulnerable to the violent invasion of Israeli citizens in uniform and also, that it remains permeable to those who observe her sufferingthat is to say, privileged citizens who do not see her condition as one of disaster, precisely, or who view it at best as a disaster contingent on ones point of view.

Aisha al-Kurds disaster, like that of millions of Palestinians governed by the state of Israel, is a regime-made disaster. A regime-made disaster is brought into being by the regime. In cases like the present one, it comes to define the regime itself and its ability to reproduce itself. The specific regime-made disaster in question is perpetuated without being acknowledged as such by those citizens who live under its reach. This civil malfunction, which does not allow for the disaster that afflicts other segments of the governed to be recognized as disaster, is one of the fundamental conditions for the appearance/disappearance of a regime-made disaster. Much of the violence that brings it into being lacks widespread attributes of violence as we commonly understand it: these acts are neither spontaneous nor are they random, chance outbreaks. On the contrary, they form part of an organized, regulated and motivated system of power that is nourished by the institutions of the democratic state, which in turn is sheltered under their umbrella. My fundamental point of departure in this book consists in the claim that, under the conditions of regime-made disaster, the first step in the evolution of a civil discourse lies in the act of refusing to identify disaster with the population upon whom it is afflicted. It consists in the refusal to see the disaster as a defining feature, precisely, of this population as expressed, for example, in the phrase Palestinian refugee. A civil discourse is thus one that suspends the point of view of governmental power and the nationalist characteristics that enable it to divide the governed from one another and to set its factions against one another. When disaster is consistently imposed on a part of the whole population of the governed, civil discourse insists on delineating the full field of vision in which the disaster unfolds so as to lay bare the blueprint of the regime. Civil discourse is not a fiction. It strives to make way for a domain of relations between citizens on the one hand, and subjects denied citizenship by a given regime on the other, on the basis of their partnership in a world that they share as women and men who are ruled. It seeks to isolate potential factors in the real world that might facilitate the coming into being of such relations of partnership, instead of the power of the sovereign that threatens to destroy them.