PHOTOGRAPHY AND ITS VIOLATIONS

Columbia Themes in Philosophy, Social Criticism, and the Arts Lydia Goehr and Gregg M. Horowitz, Editors

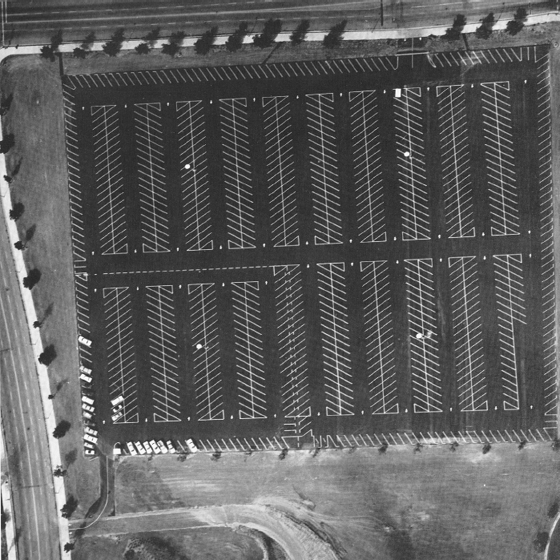

Century City, 1800 Avenue of the Stars ( Ed Ruscha. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery)

PHOTOGRAPHY

AND ITS VIOLATIONS

JOHN ROBERTS

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53824-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roberts, John, 1955

Photography and its violations / John Roberts.

pages cm (Columbia themes in philosophy, social criticism, and the arts)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16818-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53824-4 (ebook)

1. PhotographyPhilosophy. 2. PhotographySocial aspects. 3. PhotographyInfluence. I. Title.

TR183.R6324 2014

770. 1dc23

2014009808

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Jacket design by Noah Arlow

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

Many people over the years have played a part in the formation of this book as colleagues, confidants, collaborators, commissioning editors, students, conference and seminar organizers, and interlocutors. I would like to thank Jorge Ribalta, Steve Edwards, Blake Stimson, Sergio Mah, David Campany, Robin Kelsey, Andrew Warstat, Devin Fore, David Green, Andrew Yarnold, Anna Lovatt, Julian Stallabrass, Richard West, Sina Najafi, Alan Radley, Robert Grose, Mette Sandbye, Diarmuid Costello, Jan Baetens, Julia Peck, Margarida Medeiros, Malcolm Bull, Stephen Wright, Duncan Higgins, and Johan Sandborg. Also particular thanks to Jeff Wall for our discussions over the years (our differences are always productive), to Ben Seymour for the many conversations we have had on abstraction, nonreproduction, and the value-form, to Andy Fisher, John Timberlake, and Simon Baker for reading the manuscript in its different versions, to Chris Gomersall for picture research, and to Ed Ruscha and the Gagosian Gallery for permission to reproduce the frontispiece and to Tommy Spree at the Anti-War Museum in Berlin to reproduce the image from Krieg dem Kriege. And finally thanks to the four anonymous reviewers for Columbia University Press, whose comments were very helpful and insightful, and to Wendy Lochner for seeing Photography and Its Violations through its multiple stages of production, and to the series editors Lydia Goehr and Gregg Horowitz for their unstinting commitment to the book.

, Violence, Photography, and the Inhuman, was first presented as Violence, Representation and the Inhuman at the Academic Higher Research Council workshop Representations of Illness, Loughborough University, 2008, then in an amended form at the conference Violence and Representation, Tate, London, 2010, and at Ruskin College, Oxford University, and Bergen National Academy of the Arts, 2011; and a version of another section was presented as Pointing To: Ostension, Trauma and the Photographic Document at Photography and the Limits of the Document, Tate, London, 2003, and at the Conference of the Society of European Philosophy, University of Essex, 2003, and then published in a revised version in Parallax, as Pointing To: Ostension, Trauma and the Photographic Document, vol. 16, issue 2, no. 55 (2010).

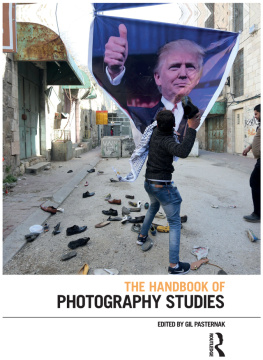

This book is the result of a long gestation process, in which I have continually returned to photography in order to chew at it again, like a dog with a recalcitrant bone. Indeed, this duality of photographyits intractability and restless assertivenessis something that is not only mentioned by many writers on photography, but in certain instances has constituted the very ground of engagement with its form and history, as in Roland Barthess Camera Lucida. This book is no different. For what makes photography worth returning to and chewing over again (and again) is precisely its unstable and destabilizing character, or what I call its productive capacity for violation. By this I mean that photographys capacity for pointing at as an act of disclosure invites the ruination of self-identity and the denaturalization of appearances, which, as such, far from these powers of ostension objectifying or reifying persons or things, are indivisible from photographys claims to truth. Indeed, what gives photography its politically exacting and philosophically demanding identity is, first and foremost, its unquenchable social intrusiveness and invasiveness, and, as such, its infinite capacity for truth-telling. Pointing to as an act of violation, then, opens up a space of nonidentity between the visible identity of a person or thing and its position within the totality of social relations in which the representation of the person or thing is made manifest. That is, in a photograph there exists empirical evidence of the palpable truth of appearances (this looks like), but also evidence of the social determination of these appearances (this looks likebecause of); and this evidence will thereby form the causal and interpretative basis for the discursive reconstruction of the image. Hence when I talk of violation, I am talking not simply about how some well-composed photographs expose social contradiction or the mechanisms of ideology in a self-evident way (the starving African child next to a well-fed aid worker), and, therefore, how such photographs offer an image that is unambiguously grievous or shaming, but about how violation is, in a sense, built into the photographic reproduction of appearances: that is, photography is the very act of making visible and, therefore, is conceptually entangled with what is unconscious, half-hidden, implicit. This is why violation is in itself embedded in, and is an effect of, power relations and materials interests external to the act of photography itself. Photography violates precisely because social appearances hide, in turn, division, hierarchy, and exclusion. But this does not mean that the photographer willingly invites this violating power into his or her practice, even if the violations of photography act objectively against the conscious intentions of the photographer. The photographer, rather, is always faced, given the circumstances under which he or she photographs, with an ethical choice: to secure or advance photographys truth-claims on the basis of these powers of violation or to diminish or veil these powers in order to either protect those in power (the conservative option) or protect the integrity of persons and things (the left/liberal option). Photographys immanent powers of violation, therefore, are something that constantly challenges and tests the photographer at the point of production and in the darkroom or at the computer. Thus, whatever political content accrues to a photographers powers of violation in any given social context, these powers of violation are not in and of themselves a univocal progressive force, as if everything needs to be made visible, at all times, under all circumstances, and with the same level of intensity and candor. On the contrary, what in some circumstances might need to be made visible at all costs in other circumstances may need to be occluded or veiled, made apparitional or allegorical. Yet violation in the form of pointing to, as inscribed in the documentary photograph, is the motive force of photographys truth-telling powers, and as such, predetermines other claims to truth on the part of other kinds of photographic practice.

New York

New York