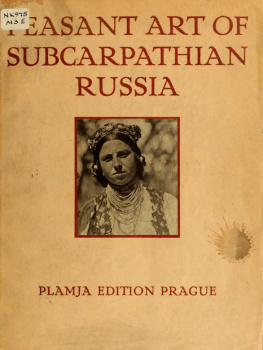

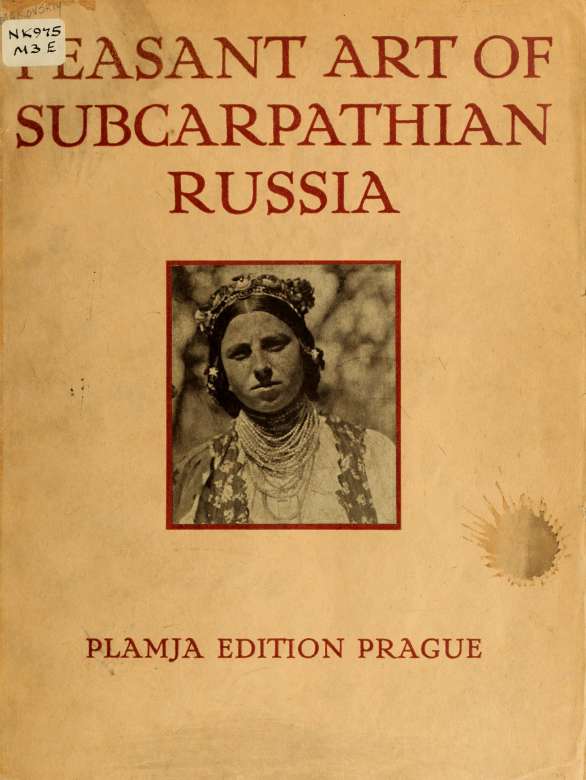

Makovskiĭ S.K. - Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia

Here you can read online Makovskiĭ S.K. - Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Introduction

Carving

Ceramics

Costume and personal decoration

Weaving and embroideries

Syllabus of illustrations

Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

PREFACE

By J. Gordon

"Many sensible things banished from high life find asylum with the mob"

Herman Melville

It is comparatively of recent time that "peasant" art has won any respect from the, so-called, art lover. A mere hundred years ago it had but scant consideration. Then the connoisseur might have indulgently conceded: "Aye. Poor ignorant fellow, he was doing his best". And thus a true word would have been uttered in contempt. He was doing his best indeed: though he who so judged it could not have done better, nor indeed in many cases could the thing along its particular line have been bettered by anybody.

Now, we may justly say that peasant art has won its right to serious consideration, and we must eagerly welcome all volumes such as this which enlarge our acquaintance with and our knowledge of little known areas of characteristic art. But may we not ask, what is "peasant" art ?

Is it not something made by the people for the people's use, something accepted as quite natural, enjoyed without unnecessary clamour by the people for whom it was made ? Essentially peasant art is something rooted in the natural culture of the people. So perhaps it might be easier to answer what is not peasant art. Actually non-peasant art seems to have existed only once now. The developments of European art since the Renaissance are, I believe, the first appearance of non-peasant art in the history of the world. All the other developments, even including the Greek, are in root peasant arts.

To-day we are prone to talk of Art as a thing unusual, to hold the artist as an exceptional man. We act as though man had a natural bent towards ugliness, as though even aesthetically he was cursed with original sin, from which he is saved by the miracle of Art. Nonsense. No community of men has existed with the material possibilities of creating art which has not created art. This proves the fallacy of our modern assumption. Art does not spring from the elevated state of man's intellect, it springs from the natural state of his intelligence. Left to himself the natural man with leisure begins to create art. Massed into communities, directed by the memories of leading intelligences who have moulded the broader aspects of the Arts' character, heritors of an ever-stretching line of tradition, the natural man gives rein to his artistic impulse and creates easily and spontaneously.

This does not invalidate the worth of his production; a thing is not necessarily valuable because it is difficult. But what shines out clearly is that under normally quiescent conditions man strives to create around himself a unity, unconsciously he evolves a decorative scheme, and everything he touches is at last moulded into one consistent harmony. Man with freedom and with leisure must drift towards beauty as inevitably as the flower turns to the sun. All the peasant arts of the world, all things that man has made for his own use, or to explain his beliefs, are infused with that beauty which comes so easily and unconsciously from the peasant craftsman's hand.

It may seem a paradox to talk of man with freedom bound by a tradition. But indeed tradition is the purest form of freedom, limitations which are unperceived allow the greatest possible liberty within those limitations. With tradition to guide him each artist works to the top of his powers, the less gifted imitates, the second rank varies and rearranges it is astonishing how many of this kind there are only the supreme artist dares to innovate. So, freed from the incubus of drastic recreation the mass of artist workers can concentrate their whole care upon subtlety and minor invention. Working in this way the average artist is most happy. I think that the carvers of the Gothic period, or of Egypt or of Assyria were the most fortunate of men. So it was with these peasant craftsmen of Buthenia. The newly arisen clamour for originality even from the second rate is possibly the most pernicious influence which has ever invaded art.

The modern deluge of manufactured ugliness which has already submerged many of the peasant arts of Europe and which is quickly flowing over the rest, springs from two factors, the loss of tradition and the loss of leisure. Its operation is hurried by the illusive beauty of Bomance and by the charms of novelty. The peasant arts of Europe received their first wound at the Be-naissance when Greece was rediscovered and became cult, they got their death blow when Watt invented the steam engine. From the Benaissance onwards Art became a snobbery; the steam engine flung traditions together and leisure was hurried into the factory. So to-day we are forced to institute museums and to publish books to leave a witness of that wealth of art once broadcast over Europe, and to bear a record that man with real leisure has the true impulse towards beauty.

I regret that this impulse to beauty is not necessarily a very robust thing. Persuasive, penetrating and all pervading though it may be, it has perhaps a misty nature. It gathers density only in still atmospheres. Overpowering in its proper conditions it may yet be dissipated by a gust of external air. The peasant, sure in his own limits and working in them with rare certainty and taste, is soon confused by neiv things or by an art outside of his experience. Before the romance of manufactured goods his sense of fitness fails. The beauty of the unusual is confounded with the beauty of the natural, and from the mixture all values disappear; taste, art impulse, sense

of unity, tenets of tradition fade away and in a short while exist no longer. To try to preserve these alive by preaching is as hopeless as catching the mist in a bag. And so the sensible things that had found asylum with the mob in the end are banished from it also and rest disconsolate in echoing and chill museums, tombstones of dead glories, stripped of a half of their proper charms because reft from their natural milieu. Yet even so what satisfaction they contain.

Is it necessary to be critically persuasive about the beauty and interest of these Ruthenian Sub-Carpathian designs ? We must beware of a facile admiration for a thing merely because, though ancient, it is novel. We may blame the peasant for greedily accepting the romance of the manufactured novelty but the same danger always haunts us. Amongst the tumult of modern art clamours, amongst the flood into the world of art of all manners and varieties of aesthetic effort, from those of the prehistoric men to those of post-impressionism, no standards once prized are left. We can no longer come to art with authority, we must find our own way through the chaos. The past is not always beautiful any more than the most recent is always ugly. Yet it is safe to assume that anything which embodies the life effort of an undisturbed and simple folk is beautiful, some necessarily in a higher degree than others; and we accept these Ruthenian examples from a little known and hitherto unstudied portion of Europe, now in Czechoslovakia with wonder and delight.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia»

Look at similar books to Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Peasant art of subcarpathian Russia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.