To

The East Room Gang

So as regards these two great obelisks

Wrought with electrum by my majesty for my father Amun

In order that my name may endure in this temple

For eternity and everlastingness

They are each made of one block of hard granite

Without seam, without joining together

INSCRIPTION ON THE BASE OF AN OBELISK

RAISED BY THE PHARAOH HATSHEPSUT

The obelisk is not an arbitrary structure, Its objects, forms and proportions were fixed by the usage of thousands of years; they satisfy every cultivated eye, and I hold it an esthetical crime to depart from them.

GEORGE PERKINS MARSH

It seems to be a peculiarity of operations with obelisks that unforeseen hitches will occur and cause delay.

LIEUTENANT SEATON SCHROEDER, USN

Every object in a state of uniform motion tends to remain in that state of motion unless an external force is applied to it.

SIR ISAAC NEWTON

CONTENTS

PREFACE

At 1:51 in the afternoon of August 23, 2011, the ground beneath Washington, D.C., began to move. People fled from buildings, trains halted, objects fell off shelves, roads cracked. It was not a killer earthquake, but at 5.8 on the Richter scale, it was the most powerful earthquake east of the Mississippi since 1944 and it did considerable damage.

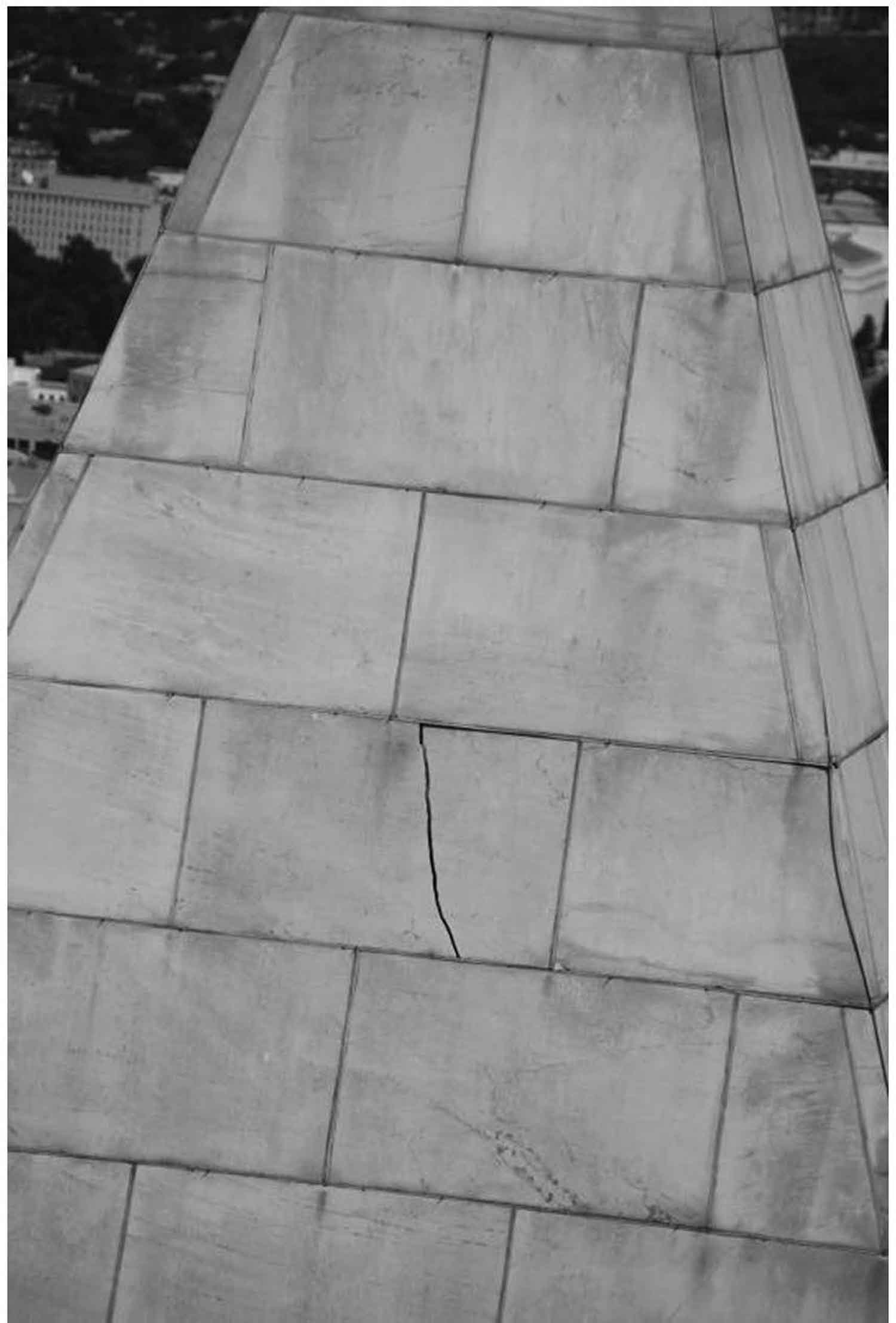

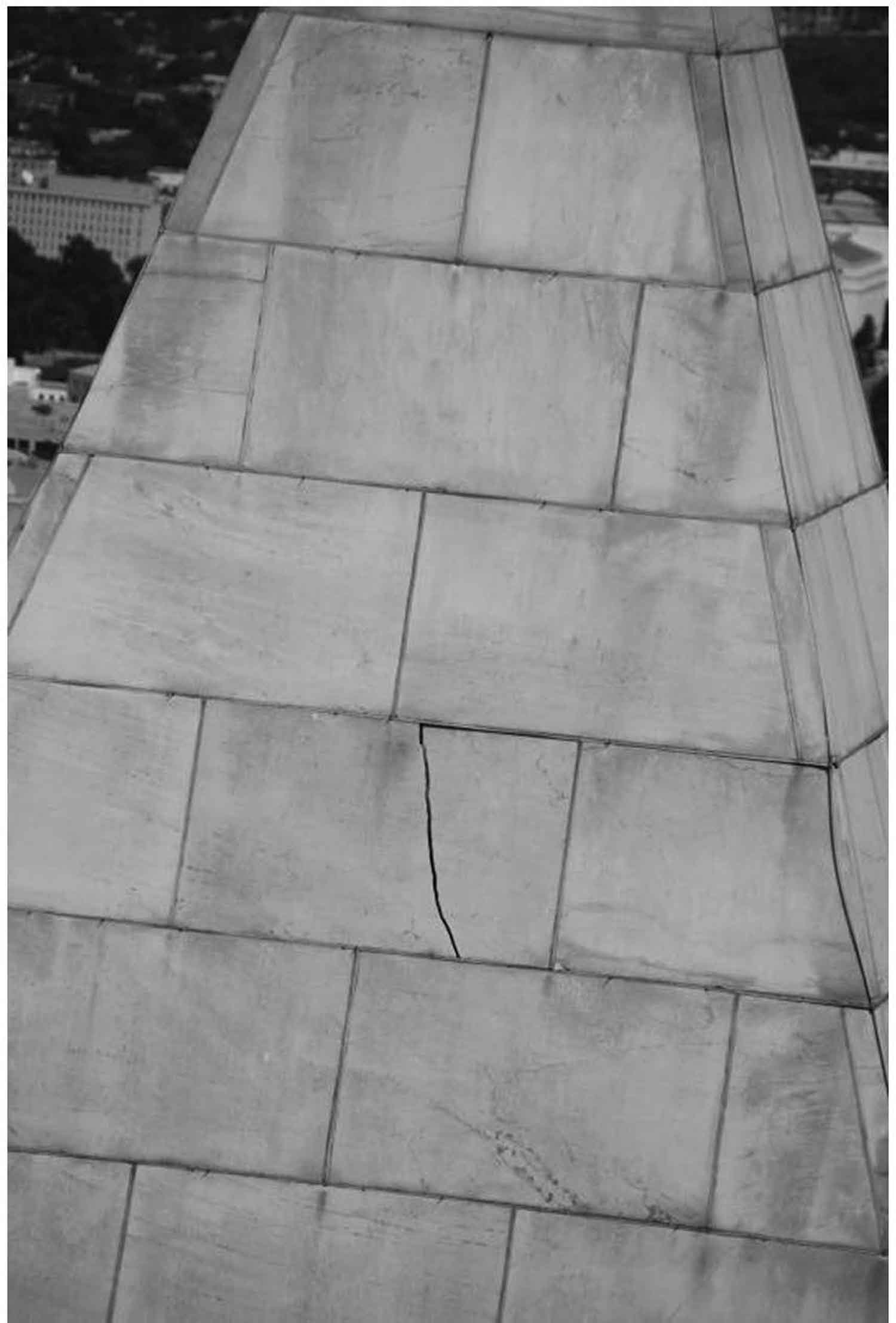

Among the casualties was one of the capitals most famous structures, the Washington Monument. Except for its elevator shaft and stairway, the monument is constructed entirely of stone, more than thirty-six thousand separate blocks. And stone structures are highly intolerant of earthquakes. Unlike wooden and steel buildings, they cannot flex as the seismic waves pass through the earth, shaking everything above. Instead, stone structures crack. Making matters worse, the Washington Monument is an obelisk, ten times as tall as it is wide at the base and weighing fully 90,854 tons and thus more vulnerable than wider, squatter buildings.

And crack it did. The most heavily damaged part was the pyramidion, the pyramid shape at the top, where many of the stones cracked or had pieces chipped off. But damage was done to the entire structure, especially at the corners. Much mortar between the massive stone blocks was lost. Daylight coming through the cracks could be seen from the inside in some places.

Earthquake damage to the Washington Monument, August 23, 2011.

While the monument came nowhere close to falling down, it was in need of serious repair, for otherwise water would be able to penetrate into the structure and eventually destroy it. Before one of the capitals most iconic structures was again open to the public, the repairs would cost fifteen million dollars and take nearly three years.

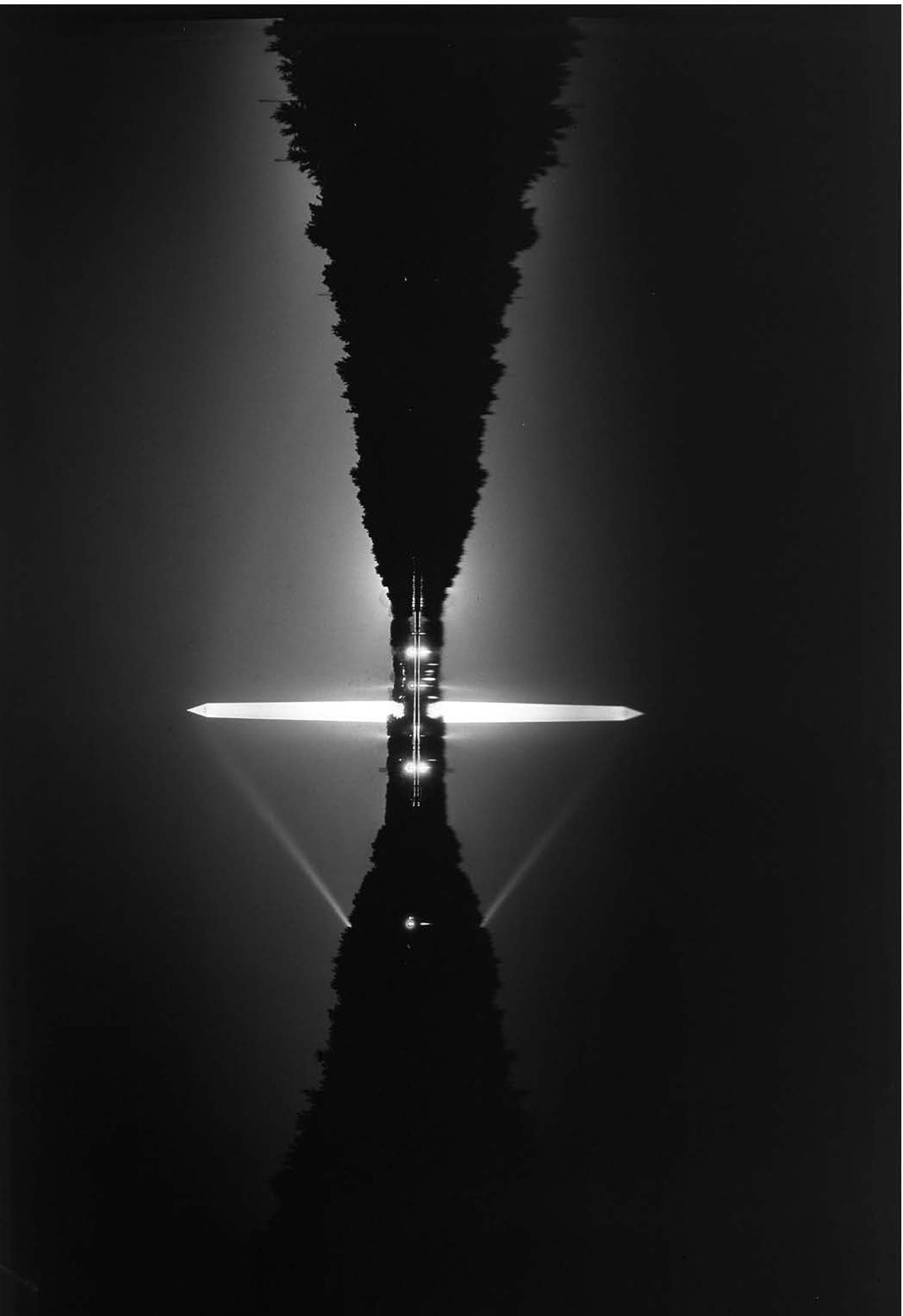

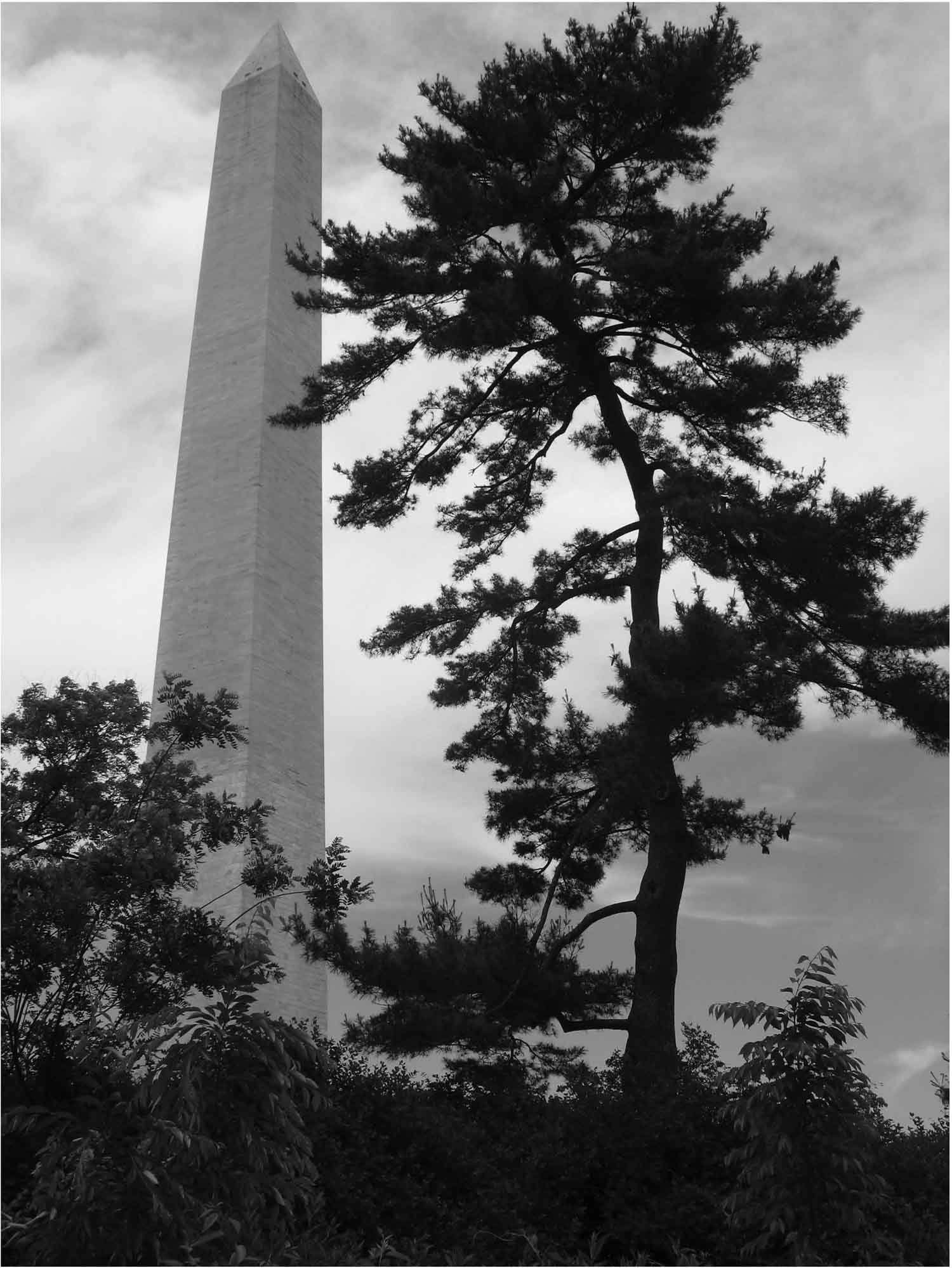

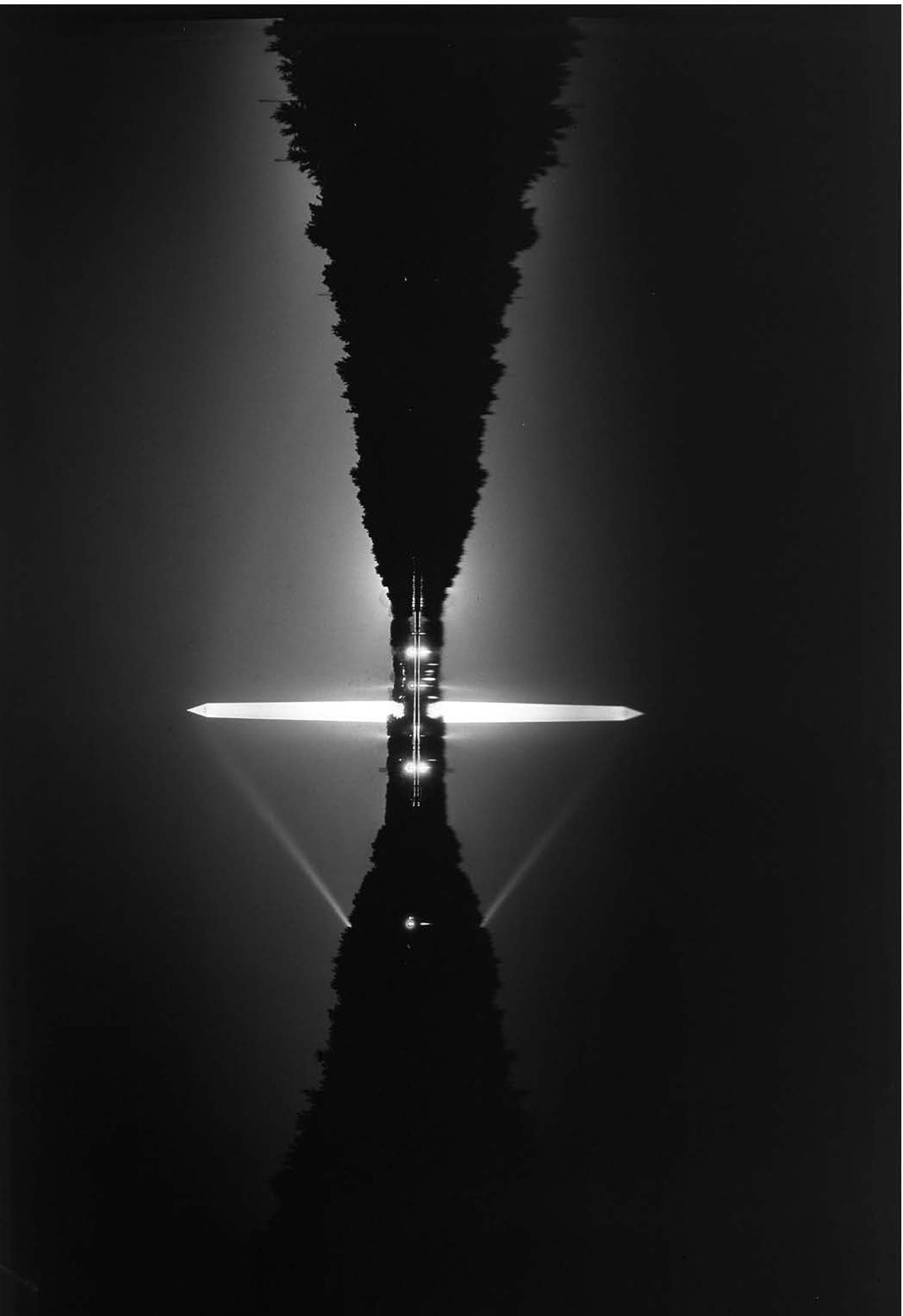

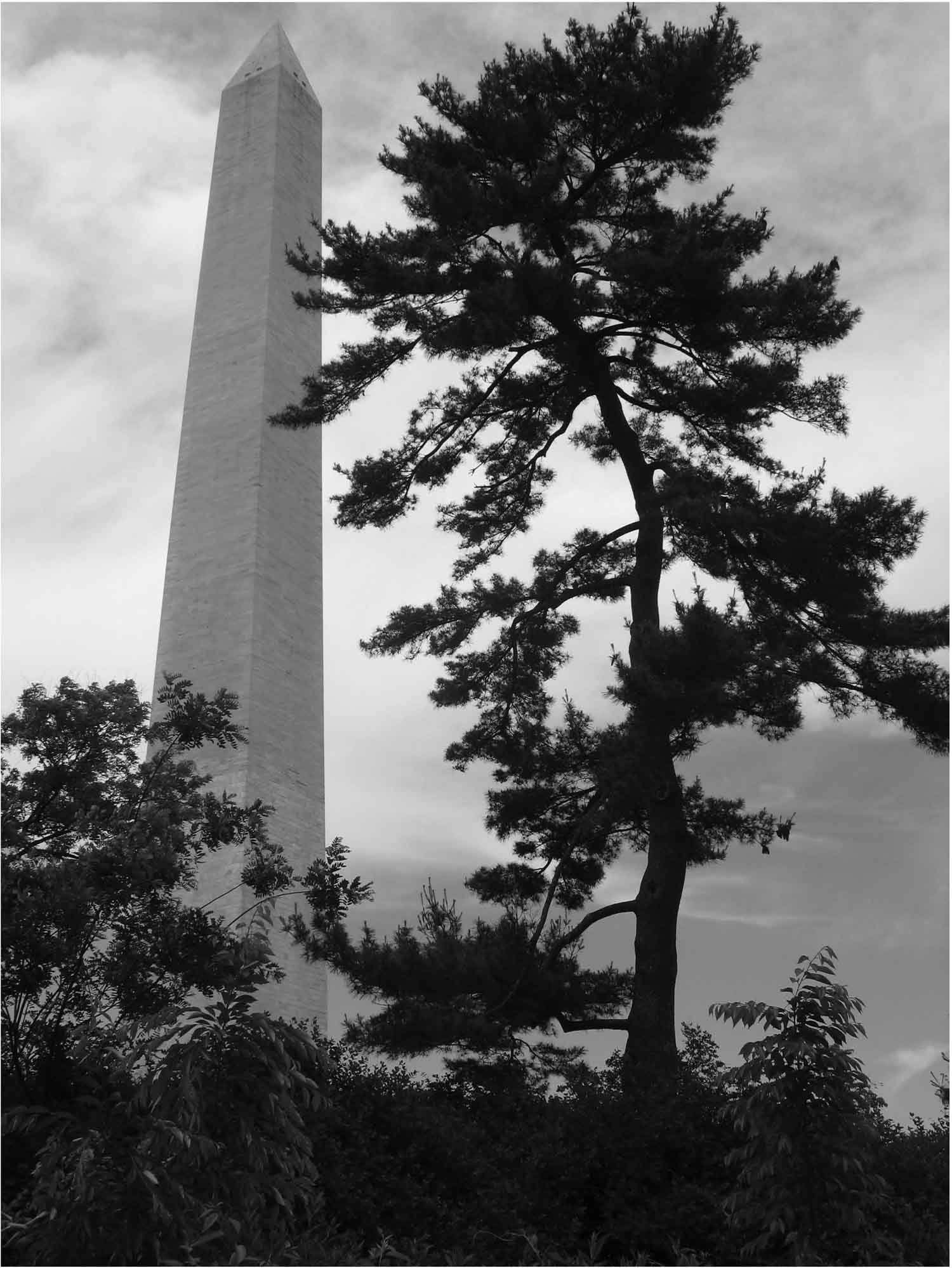

Washington without the Washington Monument is almost unimaginable today. The tallest structure, by law, in the city, it is visible from all parts of the metropolis. The view from the top is spectacular, which is one reason it has six hundred thousand visitors a year.

And while the Capitol Building symbolizes Congress and the American nation, and the White House the presidency, the Washington Monument has come to symbolize the city itself, much as Big Ben symbolizes London and the Eiffel Tower Paris. Like those two iconic structures, the monument is tall and dominates its surroundings. But it is far simpler in design, and any child, however untalented, could draw a picture of it. Its power comes as much from its simplicity as from its size.

Like all obelisks, the monument is merely four identical sides, each a greatly elongated trapezoid, capped with a four-sided pyramid, whose sides slope at a seventy-three-degree angle from the horizontal. It soars more than 555 feet into the sky, the tallest stone structure on earth and, by far, the largest obelisk, its white marble facing gleaming on sunny days.

The Washington Monument today.

The Washington Monument has always been the odd man out of the capital city of the United States. Most of the major buildings, such as the Capitol, the White House, the Treasury, the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, and the Supreme Court, were inspired by Roman and Greek architectural models. Other major buildings, such as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building west of the White House, the original Smithsonian Institution building, the Pentagon, the State Department, and the Kennedy Center, were designed in the architectural (and bureaucratic) fashions of their own day.

But the Washington Monument has architectural roots that vastly predate even the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome, let alone the Victorian age that saw its erection. It is, instead, modeled on a style of monument that was perfected in ancient Egypt during the period known as the New Kingdom (circa 15501077 B.C. ), when Egyptian power reached its zenith under such pharaohs as Thutmose III and Rameses II.

The Egyptian obelisks that now adorn such cities as Rome, Istanbul, Paris, London, and New York all date from the height of the New Kingdom. But it is a bit hard to grasp just how ancient they are. As Seaton Schroeder, the assistant engineer in charge of bringing the New York obelisk to Central Park in 1881, wrote in an appendix to the book by Henry Gorringe, the chief engineer of that project,

This mighty monument of hoary antiquity is an enduring tablet whereon the hierologist may decipher the secrets of a remoter past. From the carvings on its face we read of an age anterior to most events recorded in ancient history; Troy had not fallen, Homer was not born, Solomons temple was not built; and Rome arose, conquered the world, and passed into history during the time that this austere chronicle of silent ages has braved the elements.

Unlike the other presidential memorials in Washington, the centerpiece of the Washington Monument is the monument itself, not the statue of the man honored. Daniel Chester Frenchs magnificent, oversize statue of the seated Abraham Lincoln dominates the building that houses it and Thomas Jeffersons bronze statue is the centerpiece of his memorial. But the statue of George Washington in his monument is in an inconspicuous niche on the ground floor and receives little attention. Indeed, it was very much an afterthought, placed there only in 1994, more than a century after the monuments completion. It is the monument itself that people come to visit.

And in a city that values symmetry, while it is on the axis running between the Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial, the monument is a few hundred yards east of the axis between the White House and the Jefferson Memorial. It thus misses being in the crossing of the cruciform design of ceremonial Washington.

Perhaps most curious of all, it is utterly devoid of ornament, the very antithesis of the architectural fashion of the high Victorian years during which it was constructed, between 1848 and 1884. But that was more by accident than by design.

Next page