title

:

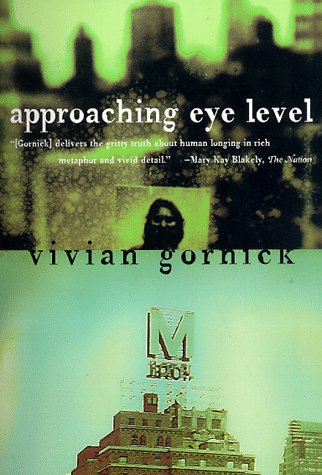

Approaching Eye Level

author

:

Gornick, Vivian.

publisher

:

Beacon Press

isbn10 | asin

:

0807070912

print isbn13

:

9780807070918

ebook isbn13

:

9780807070369

language

:

English

subject

Gornick, Vivian, Women--New York (State)--New York--Biography.

publication date

:

1996

lcc

:

HQ1439.N6G67 1996eb

ddc

:

305.4/09747

subject

:

Gornick, Vivian, Women--New York (State)--New York--Biography.

CONTENTS

1 On the Street: Nobody Watches, Everyone Performs

A writer who lived at the end of my block died. I'd known this woman more than twenty years. She admired my work, shared my politics, liked my face when she saw it coming toward her, I could see that, but she didn't want to spend time with me. We'd run into each other on the street, and it was always big smiles, a wide embrace, kisses on both cheeks, a few minutes of happy unguarded jabber. Inevitably I'd say, "Let's get together." She'd nod and say, "Call me." I'd call, and she'd make an excuse to call back, then she never would. Next time we'd run into each other: big smile, great hug, kisses on both cheeks, not a word about the unreturned call. She was impenetrable: I could not pierce the mask of smiling politeness. We went on like this for years. Sometimes I'd run into her in other parts of town. I'd always be startled, she too, New York is like a country, the neighborhood is your town, you spot someone from the block or the building in another neighborhood and the first impulse to the brain is, What are you doing here? We'd each see the thought on the other's face and start to laugh. Then we'd both give a brief salute and keep walking.

Six months after her death I passed her house one day and felt stricken. I realized that never again would I look at her retreating back thinking, Why doesn't she want my friendship? I missed her then. I missed her terribly. She was gone from the landscape of marginal encounters. That landscape against which I measure daily the immutable force of all I connect with only on the street, and only when it sees me coming.

At Thirty-eighth Street two men were leaning against a building one afternoon in July. They were both bald, both had cigars in their mouths, and each one had a small dog attached to a leash. In the glare of noise, heat, dust, and confusion, the dogs barked nonstop. Both men looked balefully at their animals. "Yap, yap, stop yapping already," one man said angrily. "Yap, yap, keep on yapping," the other said softly. I burst out laughing. The men looked up at me, and grinned. Satisfaction spread itself across each face. They had performed and I had received. My laughter had given shape to an exchange that would otherwise have evaporated in the chaos. The glare felt less threatening. I realized how often the street achieves composition for me: the flash of experience I extract again and again from the endless stream of event. The street does for me what I cannot do for myself. On the street nobody watches, everyone performs.

Another afternoon that summer I stood at my kitchen sink struggling to make a faulty spray attachment adhere to the inside of the faucet. Finally, I called in the super in my building. He shook his head. The washer inside the spray was too small for the faucet. Maybe the threads had worn down. I should go to the hardware store and find a washer big enough to remedy the situation. I walked down Greenwich Avenue, carrying the faucet and the attachment, trying hard to remember exactly what the super had told me to ask for. I didn't know the language, I wasn't sure I'd get the words right. Suddenly, I felt anxious, terribly anxious. I would not, I knew, be able to get what I needed. The spray would never work again. I walked into Garber's, an old-fashioned hardware store with these tough old Jewish guys behind the counter. One of them, also bald and with a cigar in his mouth, took the faucet and the spray in his hand. He looked at it. Slowly, he began to shake his head. Obviously, there was no hope. "Lady," he said. "It ain't the threads. It definitely ain't the threads." He continued to shake his head. He wanted there to be no hope as long as possible. "And this," he said, holding the gray plastic washer in his open hand, "this is a piece of crap.'' I stood there in patient despair. He shifted his cigar from one side of his mouth to the other, then moved away from the counter. I saw him puttering about in a drawerful of little cardboard boxes. He removed something from one of them and returned to the counter with the spray magically attached to the faucet. He detached the spray and showed me what he had done. Where there had once been gray plastic there was now gleaming silver. He screwed the spray back on, easy as you please. "Oh," I crowed, "you've done it!" Torn between the triumph of problem-solving and the satisfaction of denial, his mouth twisted up in a grim smile. ''Metal," he said philosophically, tapping the perfectly fitted washer in the faucet. "This," he picked up the plastic again, "this is a piece of crap. I'll take two dollars and fifteen cents from you." I thanked him profusely, handed him his money, then clasped my hands together on the counter and said, "It is such a pleasure to have small anxieties easily corrected." He looked at me. "Now," I said, spreading my arms wide, palms up, as though about to introduce a vaudeville act, "you've freed me for large anxieties." He continued to look at me. Then he shifted his cigar again, and spoke. "What you just said. That's a true thing." I walked out of the store happy. That evening I told the story to Laura, a writer. She said, "These are your people." Later in the evening I told it to Leonard, a New Yorker. He said, "He charged you too much."

Street theater can be achieved in a store, on a bus, in your own apartment. The idiom requires enough actors (bit players as well as principals) to complete the action and the rhythm of extended exchange. The city is rich in both. In the city things can be kept moving until they arrive at point. When they do, I come to rest.

I complain to Leonard of having had to spend the evening at a dinner party listening to the tedious husband of an interesting woman I know.

"The nerve," Leonard replies. "He thinks he's a person too."

Marie calls to tell me Em has chosen this moment when her father is dying to tell her that her self-absorption is endemic not circumstantial.

"What bad timing," I commiserate.

"Bad timing!" Marie cries. "It's aggression, pure aggression!" Her voice sounds the way cracked pavement looks.

Lorenzo, a nervous musician I know, tells me he is buying a new apartment.

"Why?" I ask, knowing his old apartment to be a lovely one.

"The bathroom is twenty feet from the bedroom," he confides, then laughs self-consciously. "I know its only a small detail. But when you live alone it's all details, isn't it?"

I run into Jane on the street. We speak of a woman we both know whose voice is routinely suicidal. Jane tells me the woman called her the other day at seven ayem and she responded with exuberance. "Don't get me wrong," she says, "I wasn't being altruistic. I was trying to pick her up off the ground because it was too early in the morning to bend over so far. I was just protecting my back."

My acquaintanceship, like the city itself, is wide-ranging but unintegrated. The people who are my friends are not the friends of one another. Sometimes, when I am feeling expansive and imagining life in New York all of a piece, these friendships feel like beads on a necklace loosely strung, the beads not touching one another but all lying, nonetheless, lightly and securely against the base of my throat, magically pressing into me the warmth of connection. Then my life seems to mirror an urban essence I prize: the dense and original quality of life on the margin, the risk and excitement of having to put it all together each day anew. The harshness of the city seems alluring. Ah, the pleasures of conflict! The glamour of uncertainty! Hurrah for neurotic friendships and yea to incivility!

Next page