Contents

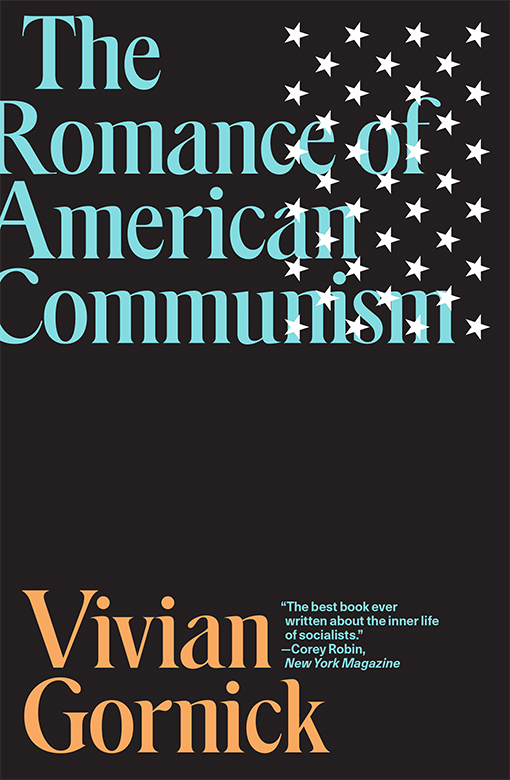

The Romance of American

Communism

THE ROMANCE

OF AMERICAN

COMMUNISM

Vivian Gornick

This paperback edition published by Verso 2020

First published by Basic Books, Inc. 1977

Vivian Gornick 1977, 2020

Excerpt from American Hunger by Richard Wright, copyright

1944 by Richard Wright, copyright 1977 by Ellen Wright,

reprinted by permission of Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-550-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-551-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-552-0 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

This book is dedicated to

the memory of Louis Gornick

and the spirit of Carl Marzani

Let us acquit ourselves so that we shall not perish without having truly existed.... The worst thing that could happen to us would be to die without either succeeding or understanding.

Simone Weil

CONTENTS

I wish to thank the Tamiment Library for letting me make use of its research materials and the Victor Rabinowitz Foundation for the financial assistance I received during the writing of this book.

One summer night in the early sixties, at a rally in New York City, the Cold War liberal Murray Kempton admitted to an audience full of old Reds that while America had not been kind to them, it had been lucky to have them. My mother was in the audience that night and said, when she came home, America was fortunate to have had the Communists here. They, more than most, prodded the country into becoming the democracy it always said it was. I was surprised by the gentleness in her voice, shed always been a hot under the collar socialist; but then again it was the sixties, and by then she was really tired.

The Communist Party USA was formed in 1919, two years after the Russian Revolution. Over the next forty years it grew steadily from a membership roll of two or three thousand to, at the height of its influence in the 1930s and 40s, seventy five thousand. All in all, nearly a million Americans were Communists at one time or another. While it is true that the majority joined the Communist Party in those years because they were members of the hard-pressed working class (garment district Jews, West Virginia miners, California fruit pickers), it was even truer that many more in the educated middle class (teachers, scientists, writers) joined because for them, too, the party was possessed of a moral authority that lent concrete shape to a sense of social injustice made urgent by the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Most American Communists never set foot in party headquarters, nor laid eyes on a Central Committee member, nor were privy to internal party policy-making sessions. But every rank-and-filer knew that party unionists were crucial to the rise of industrial labor in this country; that it was mainly party lawyers who defended blacks in the deep South; that party organizers lived, worked, and sometimes died with miners in Appalachia, farm workers in California, steel workers in Pittsburgh. On a day to day basis, through its passion for structure and the eloquence of its rhetoric, the party made itself feel real and familiar not only to its own members but to the immensely larger world then existent of sympathizers and fellow travelers. It had built a remarkable network of regional sections and local branches; schools and publications; organizations that addressed large home-grown miseriesthe International Workers Order, the National Negro Congress, the Unemployment Councilsand an in-your-face daily newspaper that liberals as well as radicals regularly read. As one old Red put it, Whenever some new world catastrophe announced itself throughout the Depression and World War II, the Daily Worker sold out in minutes.

It is perhaps hard to understand now, but at that time, in this place, the Marxist vision of world solidarity as translated by the Communist Party induced in the most ordinary of men and women a sense of ones own humanity that made life feel large; large and clarified. It was to this inner clarity that so many became not only attached, but addicted. While under its influence, no reward of life, neither love nor fame nor wealth could compete.

At the same time it was this very all-in-allness of world and self that, all too often, made of the Communists true believers who could not face up to the police state corruption at the heart of their faith, even when a ten year old could see that a double game was being played. The CPUSA was a dues-paying member of the Comintern (the International Communist organization run from Moscow) and as such, it was accountable to the Soviets who intimidated communist parties around the world into adopting policies, both domestic and foreign, that most often served the needs of the Soviet Union rather than those of the Cominterns member countries. As a result, the CPUSA turned itself inside out, time and again, to accommodate what American communists saw as the one and only socialist country in the world they were required to support at all costs. This unyielding devotion to Soviet Russia allowed American communists to deceive themselves repeatedly throughout the 30s and 40s and much of the 50s as the Soviet Union rolled over Eastern Europe and became steadily more totalitarian, its actual life ever more hidden and its demands ever more self-serving.

In the early fifties the CPUSA came under serious fire from the wild panic over American security that McCarthyism set in motionscores of Communists went underground out of fear of prison and perhaps worsebut then in 1956 the party very nearly disintegrated under the weight of its own world-shattering scandal. In February of that year Nikita Khrushchev addressed the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party and revealed to the world the incalculable horror of Stalins rule. That address brought with it political devastation for the organized left around the world. Within weeks of its delivery thirty thousand people quit the CPUSA, and within the year the party was as it had been in its 1919 beginnings: a small sect on the American political map.

I grew up in a leftwing home where the Daily Worker was read, worker politics (global and local) was discussed at the dinner table, and progressives of every type regularly came and went. It never occurred to me to think of these people as revolutionaries. Never once did I have the impression that anyone around me wanted to see the government overthrown by violence. On the contrary: I saw them as working to see socialism become the norm through a change in the law; a change that would insure that, with the defeat of capitalism, the American democracy would keep its broken promise of equality for all. In short, however nave that may have been, I saw the progressives, always, as honest dissenters.