EVERYONE KNOWS THAT TIMING IS EVERYTHING.

But we dont know much about timing itself. Our lives are a never-ending stream of when decisions: when to start a business, schedule a class, get serious about a person. Yet we make those decisions based on intuition and guesswork.

Drawing on a rich trove of research from psychology, biology and economics, Daniel H. Pink reveals how we can use the hidden patterns of the day to build the ideal schedule. How can we turn a stumbling beginning into a fresh start? Why should we avoid going to the hospital in the afternoon? Why is singing in time with other people as good for you as exercise? And what is the ideal time to quit a job, switch careers or get married?

WHEN is a fascinating and readable narrative with compelling insights into how we can lead richer, more engaged lives.

Pink is rapidly acquiring international guru status.

Financial Times

Time isnt the main thing. Its the only thing.

MILES DAVIS

CONTENTS

Across continents and time zones, as predictable as the ocean tides, was the same daily oscillationa peak, a trough, and a rebound.

A growing body of science makes it clear: Breaks are not a sign of sloth but a sign of strength.

Most of us have harbored a sense that beginnings are signicant. Now the science of timing has shown that theyre even more powerful than we suspected. Beginnings stay with us far longer than we know; their effects linger to the end.

When we reach a midpoint, sometimes we slump, but other times we jump. A mental siren alerts us that weve squandered half of our time.

Yet, when endings become salientwhenever we enter an act three of any kindwe sharpen our existential red pencils and scratch out anyone or anything nonessential.

Synchronizing makes us feel goodand feeling good helps a groups wheels turn more smoothly. Coordinating with others also makes us do goodand doing good enhances synchronization.

Most of the worlds languages mark verbs with time using tensesespecially past, present, and futureto convey meaning and reveal thinking. Nearly every phrase we utter is tinged with time.

Index

Half past noon on Saturday, May 1, 1915, a luxury ocean liner pulled away from Pier 54 on the Manhattan side of the Hudson River and set off for Liverpool, England. Some of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard the enormous British ship no doubt felt a bit queasythough less from the tides than from the times.

Great Britain was at war with Germany, World War I having broken out the previous summer. Germany had recently declared the waters adjacent to the British Isles, through which this ship had to pass, a war zone. In the weeks before the scheduled departure, the German embassy in the United States even placed ads in American newspapers warning prospective passengers that those who entered those waters on ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

Yet only a few passengers canceled their trips. After all, this liner had made more than two hundred transatlantic crossings without incident. It was one of the largest and fastest passenger ships in the world, equipped with a wireless telegraph and well stocked with life

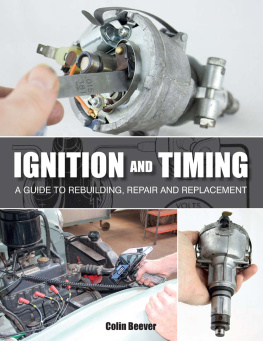

The ship traversed the Atlantic Ocean for five uneventful days. But on May 6, as the hulking vessel pushed toward the coast of Ireland, Turner received word that German submarines, or U-boats, were roaming the area. He soon left the captains deck and stationed himself on the bridge in order to scan the horizon and be ready to make swift decisions.

On Friday morning, May 7, with the liner now just one hundred miles from the coast, a thick fog settled in, so Turner reduced the ships speed from twenty-one knots to fifteen knots. By noon, though, the fog had lifted, and Turner could spy the shoreline in the distance. The skies were clear. The seas were calm.

However, at 1 p.m., unbeknownst to captain or crew, German U-boat commander Walther Schwieger spotted the ship. And in the next hour, Turner made two inexplicable decisions. First, he increased the ships speed a bit to eighteen knots but not to its maximum speed of twenty-one knots, even though his visibility was sound, the waters were steady, and he knew submarines might be lurking. During the voyage, he had assured passengers that he would run the ship fast because at its top speed this ocean liner could easily outrace any submarine. Second, at around 1:45 p.m., in order to calculate his position, Turner executed whats called a four-point bearing, a maneuver that took forty minutes, rather than carry out a simpler bearing maneuver that would have taken only five minutes. And because of the four-point bearing, Turner had to pilot the ship in a straight line rather than steer a zigzag course, which was the best way to dodge U-boats and elude their torpedoes.

At 2:10 p.m., a German torpedo ripped into the starboard side of the ship, tearing open an immense hole. A geyser of seawater erupted, raining shattered equipment and ship parts on the deck. Minutes later, one boiler room flooded, then another. The destruction triggered a second explosion. Turner was knocked overboard. Passengers screamed and dived for lifeboats. Then, just eighteen minutes after being hit, the ship rolled on its side and began to sink.

Seeing the devastation he had wrought, submarine commander Schwieger headed out to sea. He had sunk the Lusitania.

Nearly 1,200 people perished in the attack, including 123 of the 141 Americans aboard. The incident escalated World War I, rewrote the rules of naval engagement, and later helped draw the United States into the war. But what exactly took place that May afternoon a century ago remains something of a mystery. Two inquiries in the immediate aftermath of the attack were unsatisfying. British officials halted the first one so as not to reveal military secrets. The second, led by John Charles Bigham, a British jurist known as Lord Mersey, who had also investigated the Titanic disaster, exonerated Captain Turner and the shipping company of any wrongdoing. Yet, days after the hearings ended, Lord Mersey resigned from the case and refused payment for his service, saying, The Lusitania case was a damned, dirty business! During the last century, journalists have pored over news clippings and passenger diaries, and divers have probed the wreckage searching for clues about what really happened. Authors and filmmakers continue to produce books and documentaries that blaze with speculation.

Had Britain intentionally placed the Lusitania in harms way, or even conspired to sink the ship, to drag the United States into the war? Was the ship, which carried some small munitions, actually being used to transport a larger and more powerful cache of arms for the British war effort? Was Britains top naval official, a forty-year-old named Winston Churchill, somehow involved? Was Captain Turner, who survived the attack, just a pawn of more influential men,

Nobody knows for sure. More than one hundred years of investigative reporting, historical analysis, and raw speculation havent yielded a definitive answer. But maybe theres a simpler explanation that no one has considered. Maybe, seen through the fresh lens of twenty-first-century behavioral and biological science, the explanation for one of the most consequential disasters in maritime history is less sinister. Maybe Captain Turner just made some bad decisions. And maybe those decisions were bad because he made them in the afternoon.

This is a book about timing. We all know that timing is everything. Trouble is, we dont know much about timing itself. Our lives present a never-ending stream of when decisionswhen to change careers, deliver bad news, schedule a class, end a marriage, go for a run, or get serious about a project or a person. But most of these decisions emanate from a steamy bog of intuition and guesswork. Timing, we believe, is an art.

Next page