Sometimes the best way to describe something is to say what it isnt. In this sense, I would like to conclude by summarizing in a pointed way the ten biggest mistakes regarding digital supply chains.

Error No. 1: Digital supply chains will be important, but will not revolutionize our lives.

Wrong, digitalization offers the potential to build supply chains completely differently and to develop new business models. The Internet of Things is revolutionizing logistics, among other things.

Error No. 2: Digital supply chains help to reduce complexity.

Wrong, complexity can only be handled with complexity. The answer to increasing environmental and market requirements (customer expectations, regulations, scarcity of resources, etc.) is therefore resilience and flexibility.

Error No. 3: Digital supply chains mean maximum self-organization.

Wrong, the delegation of responsibility and decentralization of decisions do not mean the complete abandonment of design and development possibilities. It depends on the right scope and degree of self-organization as well as the right guardrails.

Error No. 4: Digital supply chains are an efficiency engine, but not a growth engine.

Wrong, the use of the Internet of Services in the field of supply chains offers potential for many new services and business ideas. This offers growth opportunities for companies and regions.

Error No. 5: Digital supply chains are what I do by doing a bit of cyberphysics.

Wrong, digital supply chains are more than a new technology. Cyberphysical systems make many things possible. However, digital supply chains can be implemented as a holistic management concept for individual companies. It affects all areas of management.

Error No. 6: Digital supply chains mean finding the right algorithm for forecasting.

Wrong, the relevant procedures typically offer a whole series of algorithms for a specific question. The all-healing algorithm does not exist. And not everything can be forecasted.

Error No. 7: Digital supply chains mean collecting as much data as possible.

Wrong. It is not about a comprehensive consideration of as much data as possible, but about the integration of the relevant sources. Relevant are those data that serve to achieve the supply chain goals such as forecast accuracy or resilience.

Error No. 8: Digital supply chains require big data and CPS competence but no supply chain management knowledge.

Wrong. The analysis and management of complex supply chains require not only the necessary IT and analytical competence, but also an understanding of logistics, flows and value chains, because this is precisely where judgement and business knowledge are required.

Error No. 9: Digital supply chains are already covered by the current Industry 4.0 Initiative.

Wrong. The degree of maturity of supply chains in industry is very different. Quite a few companies first have to implement minimum standards in the field of supply chain management before they can devote themselves sensibly to the subject of Industry 4.0. An Industry 4.0 without sufficient supply chains does not work.

Error No. 10: Digital supply chains are not a matter for the CXO, but a task for the logistics department.

Wrong. Digitization belongs on every board agenda. The design of the companys value creation structure and business model is strategic and critical of competition.

1

The complexity issue

The complexity problem is now on everyones lips. The increasing scope of coordination, and thus efforts to coordinate supply chains, ultimately results from the growing complexity of both the internal and external environment of enterprises (Ulrich/Probst 1991). Complexity presents itself as the product of corresponding dynamics and diversity. The increasing number and variety of relevant variables, as well as the heterogeneity of their relationships, characterize diversity. Dynamics reflect the degree of renewal of supply chainrelevant elements, as well as their relationships and effects over time. A well-known and often used abbreviation is VUCA, which stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. Slightly different definitions of VUCA have been offered, and there is little value in having a discussion about nomenclature. Dynamics and diversity, therefore, represent substantial drivers of complexity.

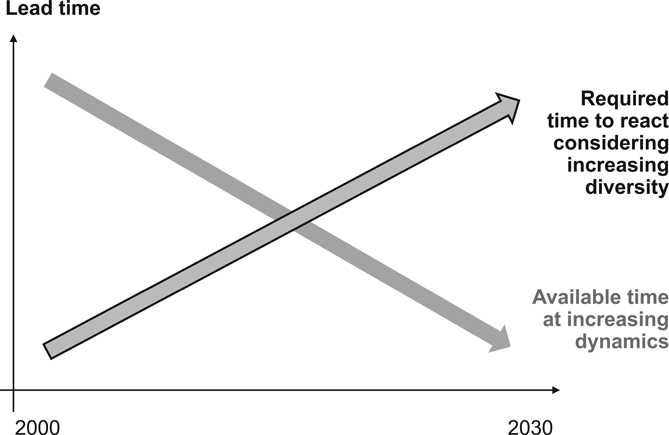

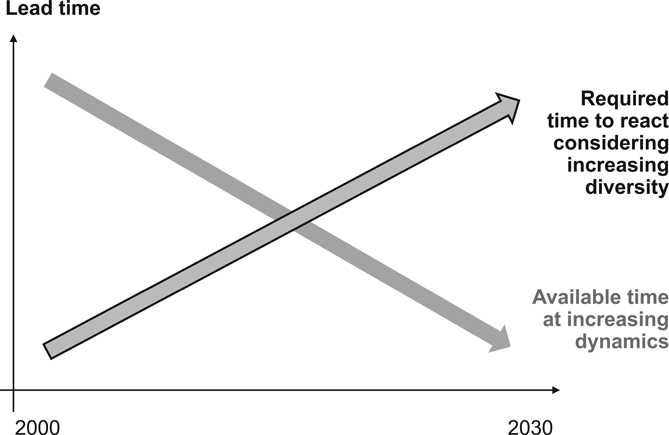

If we consider the development of the complexity of supply chainrelated parameters in recent years, we can see an overall rising trend. Higher complexity requires more time for analysis and decision making. However, the response time available to supply chain managers decreases with higher dynamics. A kind of time shear opens a gap ().

time gap of supply chain management (following Bleicher 1995, modified by Wehberg 1997)

For supply chain practitioners, the aforementioned time gap appears in the form of a whole series of relevant megatrends such as digitalization, individualization, data security needs, scarcity of resources, service competition, terrorism, tax optimization and sustainability. Moreover, unforeseen disruptions in the daily business impact the supply chain more often. For example, the production planning and detailed steering (PPDS) cycle traditionally have a freeze. Many companies are facing rush orders, reprioritization and change requests during this cycle. The companies are not able to redo the PPDS as fast as the new requests are coming in. Issues accumulate. Stocks increase, creating bottlenecks within the process, extending response times and making the situation even worse. The so-called bullwhip effect materializes. Examples for potential disruptions include infrastructure breakdowns, biological catastrophes and terrorist attacks. Supply chain management in practice has become increasingly complex in recent years, and will continue to become more so in the future.

In highly complex, non-trivial systems, statements about the effectiveness and efficiency of supply chain management can no longer be described as linearif-then relationships. In addition, long-term impacts often do not correspond to short-term effects. As a consequence, a complete analysis of the supply chain system is impossible. Supply chain management acts blindly to a certain extent. In other words, synoptic planning is no longer possible (Probst 1981).

Ten Hompel (2014) speaks in this context about a hydrostatic paradox. The classical planning of material flow systems is essentially based on so-called marginal cost calculation. In this context, the maximum performance has to be provided as the volume delivered per unit of time. The dilemma of this analytical approach in a complex environment lies in the lack of controllability of the marginal power, which means in its barely existing flexibility and resilience.

Supply chain resilience thus means the ability of the supply chain to be able to handle unforeseen events such as logistics infrastructure breakdowns, biological catastrophes or terrorist attacks (see also Weick/Sutcliffe 2001). Over and beyond external disruptions, resilience also includes the capability to cope with increasing internal complexity, such as the climbing number of make-to-order products and rush orders. In a way, of course, such internal disruptors are also a response to external developments. Bottom line, a sufficient resilience allows the companies to maintain a reasonable level of effectiveness and efficiency of their supply chain. Resilience includes both an active dimension being addressed by the concept of agility, as well as a reactive one called robustness. While resilience is a characteristic of supply chain potentials and activities, flexibility means service quality as performance criteria.