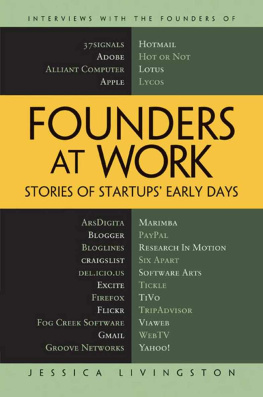

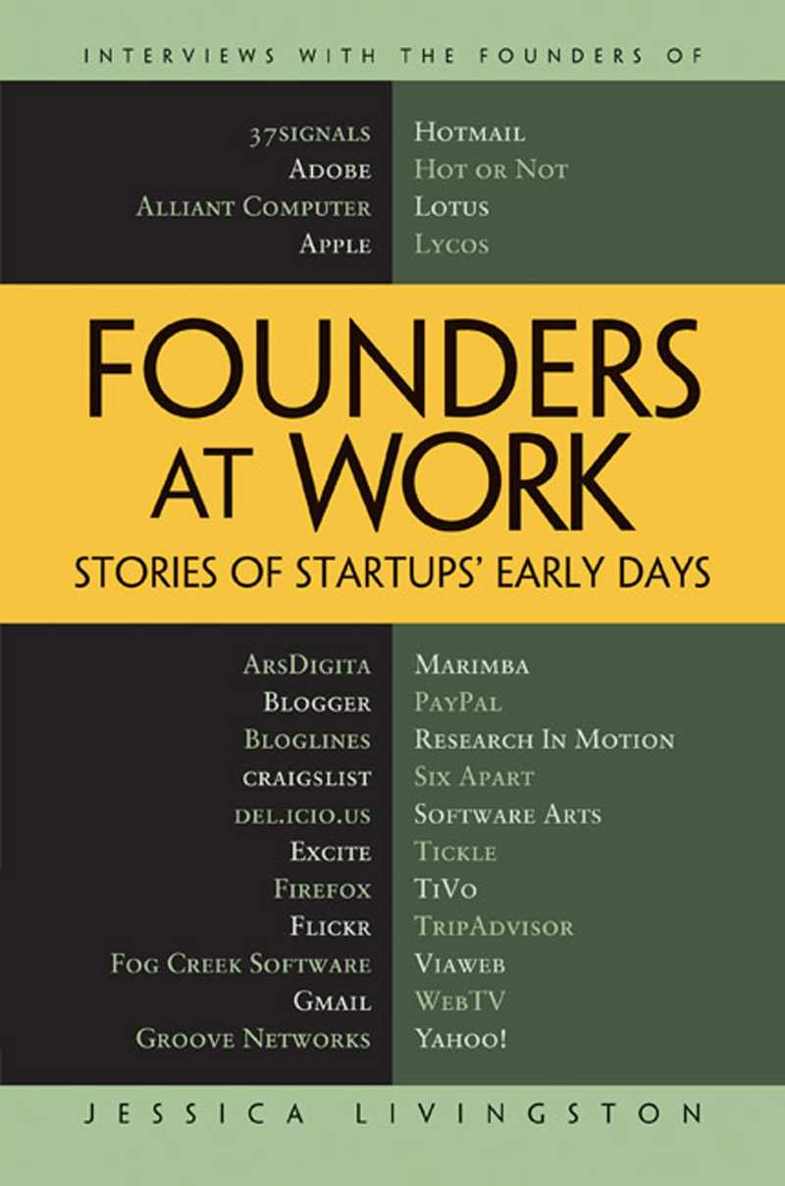

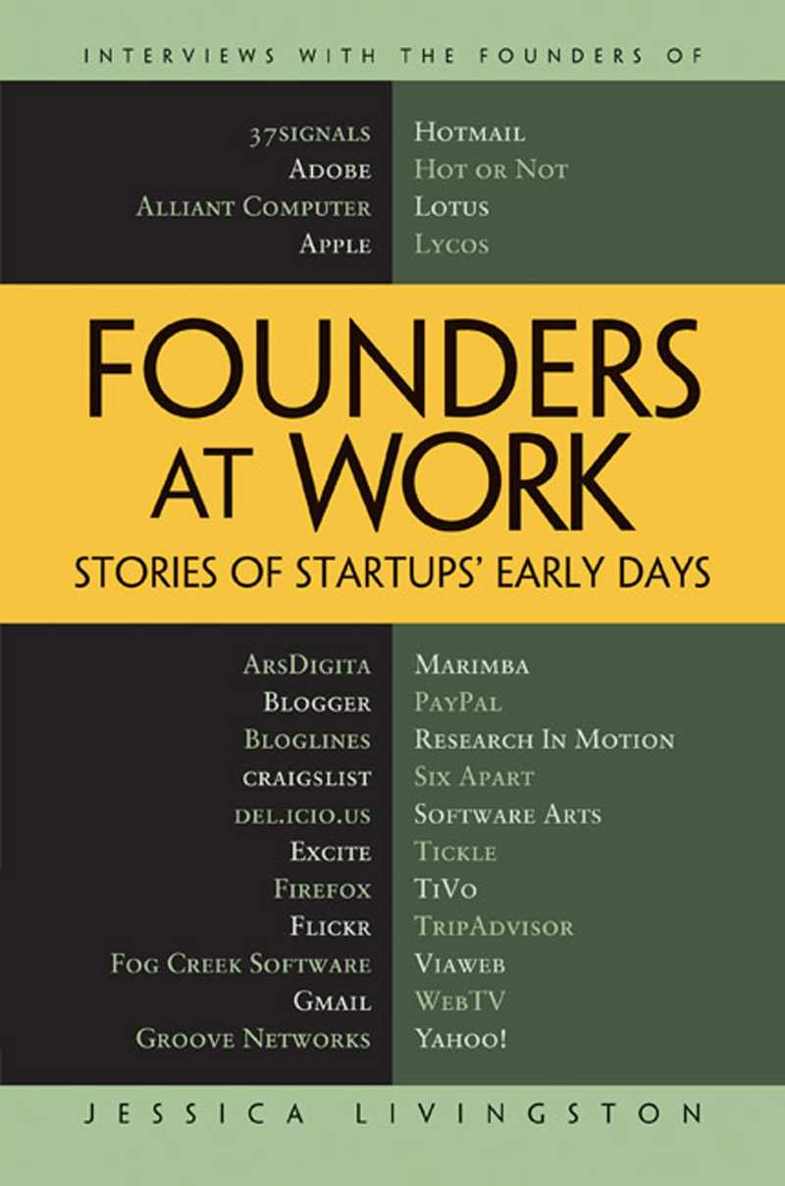

Founders at Work: Stories of Startups' Early Days

Copyright 2007 by Jessica Livingston

Lead Editor: Jim Sumser

Editorial Board: Steve Anglin, Ewan Buckingham, Gary Cornell, Jason Gilmore, Jonathan Gennick, Jonathan Hassell, James Huddleston, Chris Mills, Matthew Moodie, Dominic Shakeshaft, Jim Sumser, Matt Wade

Project Manager: Elizabeth Seymour

Copy Edit Manager: Nicole Flores

Copy Editor: Damon Larson

Assistant Production Director: Kari Brooks-Copony

Compositor: Dina Quan

Proofreader: Linda Seifert

Cover Designer: Kurt Krames

Manufacturing Director: Tom Debolski

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Livingston, Jessica.

Founders at work : stories of startups' early days / Jessica

Livingston.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-59059-714-1

1. New business enterprises--United States--Case studies. 2.

Electronic industries--United States--Case studies. I. Title.

HD62.5.L59 2007

658.1'1--dc22

2006101542

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher.

Printed and bound in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Trademarked names may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark.

Distributed to the book trade worldwide by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 233 Spring Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10013. Phone 1-800-SPRINGER, fax 201-348-4505, e-mail .

For information on translations, please contact Apress directly at 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 219, Berkeley, CA 94710. Phone 510-549-5930, fax 510-549-5939, e-mail .

The information in this book is distributed on an "as is" basis, without warranty. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this work, neither the author(s) nor Apress shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this work.

For Da and PG

Contents

Foreword

Apparently sprinters reach their highest speed right out of the blocks, and spend the rest of the race slowing down. The winners slow down the least. It's that way with most startups too. The earliest phase is usually the most productive. That's when they have the really big ideas. Imagine what Apple was like when 100% of its employees were either Steve Jobs or Steve Wozniak.

The striking thing about this phase is that it's completely different from most people's idea of what business is like. If you looked in people's heads (or stock photo collections) for images representing "business," you'd get images of people dressed up in suits, groups sitting around conference tables looking serious, Powerpoint presentations, people producing thick reports for one another to read. Early stage startups are the exact opposite of this. And yet they're probably the most productive part of the whole economy.

Why the disconnect? I think there's a general principle at work here: the less energy people expend on performance, the more they expend on appearances to compensate. More often than not the energy they expend on seeming impressive makes their actual performance worse. A few years ago I read an article in which a car magazine modified the "sports" model of some production car to get the fastest possible standing quarter mile. You know how they did it? They cut off all the crap the manufacturer had bolted onto the car to make it look fast.

Business is broken the same way that car was. The effort that goes into looking productive is not merely wasted, but actually makes organizations less productive. Suits, for example. Suits do not help people to think better. I bet most executives at big companies do their best thinking when they wake up on Sunday morning and go downstairs in their bathrobe to make a cup of coffee. That's when you have ideas. Just imagine what a company would be like if people could think that well at work. People do in startups, at least some of the time. (Half the time you're in a panic because your servers are on fire, but the other half you're thinking as deeply as most people only get to sitting alone on a Sunday morning.)

Ditto for most of the other differences between startups and what passes for productivity in big companies. And yet conventional ideas of "professionalism" have such an iron grip on our minds that even startup founders are affected by them. In our startup, when outsiders came to visit we tried hard to seem "professional." We'd clean up our offices, wear better clothes, try to arrange that a lot of people were there during conventional office hours. In fact, programming didn't get done by well-dressed people at clean desks during office hours. It got done by badly dressed people (I was notorious for programming wearing just a towel) in offices strewn with junk at 2 in the morning. But no visitor would understand that. Not even investors, who are supposed to be able to recognize real productivity when they see it. Even we were affected by the conventional wisdom. We thought of ourselves as impostors, succeeding despite being totally unprofessional. It was as if we'd created a Formula 1 car but felt sheepish because it didn't look like a car was supposed to look.

In the car world, there are at least some people who know that a high performance car looks like a Formula 1 racecar, not a sedan with giant rims and a fake spoiler bolted to the trunk. Why not in business? Probably because startups are so small. The really dramatic growth happens when a startup only has three or four people, so only three or four people see that, whereas tens of thousands see business as it's practiced by Boeing or Philip Morris.

This book can help fix that problem, by showing everyone what, till now, only a handful people got to see: what happens in the first year of a startup. This is what real productivity looks like. This is the Formula 1 racecar. It looks weird, but it goes fast.

Of course, big companies won't be able to do everything these startups do. In big companies there's always going to be more politics, and less scope for individual decisions. But seeing what startups are really like will at least show other organizations what to aim for. The time may soon be coming when instead of startups trying to seem more corporate, corporations will try to seem more like startups. That would be a good thing.

Paul Graham

Acknowledgments

I'd first like to thank my aunt, Ann Gregg, for her unfailing support and encouragement. She's an extraordinarily perceptive reader and she provided a lot of advice that helped make this a better book.

Thanks to the people I interviewed for sharing their stories and their time. One thing I noticed in the interviews that I didn't mention in the introduction is how much I liked the founders. They were genuine and smart, and it was an honor to talk with them. I know the candid nature of their stories and advice will inspire would-be founders for years to come.

Thanks to Gary Cornell for being willing to do a different kind of book, and to the Apress team for working on a different kind of book.