About the Author

Steven Stryker, president of Stryker Associates, has thirty-three years of experience in providing technical assistance, facilitation, and training in strategic planning, project management and acquisition, and contracting arenas. He has been in the forefront of combining the above three areas of expertise to ensure that timely, complete, and effective performance occurs in information technology, technical support and logistics, research and development, commercial services or a combination. Working with both private- and public-sector clients, the results from these efforts (singularly or in combination) have saved time, money, and problems, while obtaining higher-quality results.

Besides the republishing of Plan to Succeed: A Guide to Strategic Planning, Roman & Littlefield is also republishing Guide to Successful Consulting and Principles and Practices of Professional Consulting. He has also published The COTR Handbook: Effective Catalyst for Stronger Organizational Performance, which demonstrates effective contract processes and practices. Recently he contributed a chapter on research and development contracting for a forthcoming book on services contracting.

In addition, over the past three years, Mr. Stryker has been a requested speaker and presenter at a number of conferences and seminars on performance-based topics (with a focus on enhancing performance application and accountability).

Chapter 1

Discovering Strategic Planning

SNAPSHOT

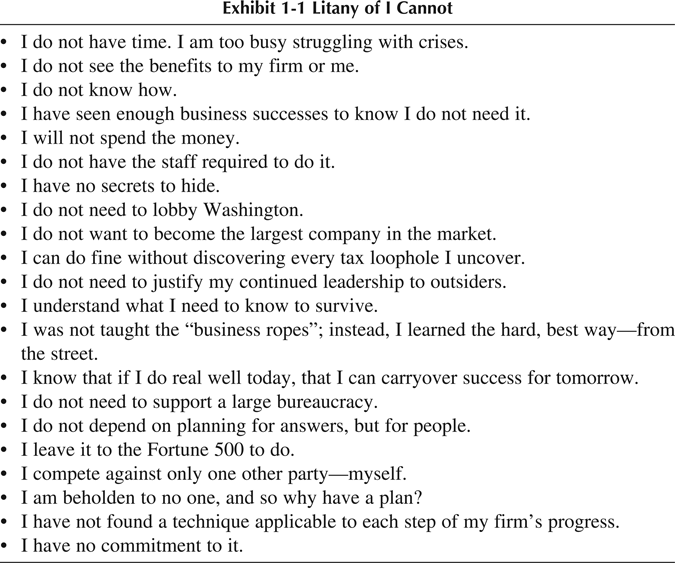

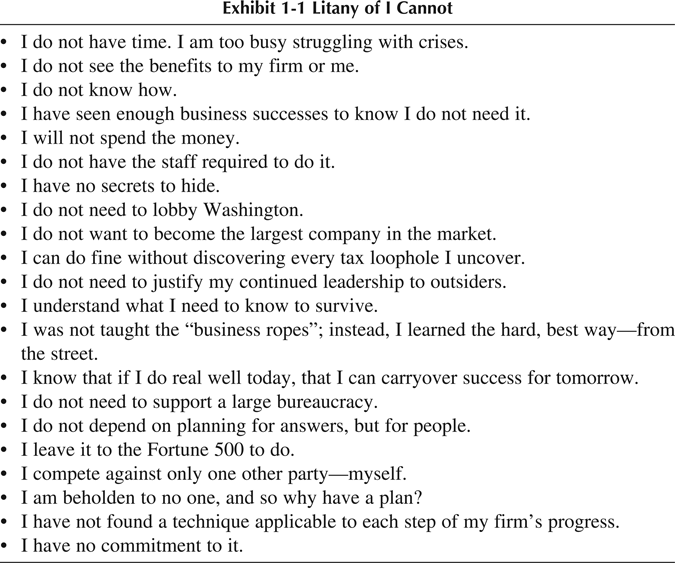

Planning began when a person said, If I had known more, I should/could have handled this situation better than I did. From this hindsight motif, we realized that if we dont learn from experiences we are bound to repeat the same mistakes. And since business success is based on doing the right things right, some forethought ought to be given to how these things can be accomplished. Yet, speak to the alter-egos of many business owners today and you will likely find several or more I Cannots, as shown in Exhibit 1-1 following. These statements become justification for ignoring, downplaying or negating the strategic planning activity. If these observations were all truthful, sensible and success stimulants, there would be nothing to write about in this book. Business would go on as usual. Instead, this chapter will present past experience as the perspective to seriously reconsider the thoughts in Exhibit 1-1.

Subsequent chapters will also handle those objections for which answers have been illusive.

DOES DOING STRATEGIC PLANNING MAKE SENSE?

Four instances of how business grows are shown in the following sections to illustrate strategic planning. Each instance is taken from an actual company, with the names and events changed for quick description. The dynamics of planning are actual in each case.

Company One: The Yellow Veranda

Set back 100 yards from a four-chambered pond, this rustic country inn has been operating well for three years. Purchased from a widow (whose family had lived there for three generations) by Eloise Newhouse, the restaurant began to turn a profit in the fourth quarter of its first operating year. How was she able to accomplish this feat in an industry where two years is not an uncommon time before a profit is turned? As she said, her success is based on strong and complete strategic planning. The genesis of her success are the forethoughts and actions she did long before opening the doors of The Yellow Veranda. First, she created a vision of her business: a place where harried urbanites could come and relax with the right combination of good food, pleasant surroundings, old-world charm, personal service and competitive prices. Next, she went out and got experience. Leaving her stockbroker position, she first became a hostess and assistant food buyer at a friends summer dinner theater. When it closed down for the winter, she found a position as an assistant manager and chef at a boutique restaurant in the revived downtown area. She worked for half the normal salary in order to gain much more than moneyexperience and incentive to open her own place.

In her spare time, during this eighteen-month apprenticeship, she slowly put together her first strategic plan for her business. She carefully culled information about country inn restaurants from books, restaurateurs, consultants, patrons, associations, and the Small Business Administration. What she found was data about everything from furnishings to budgeting to marketing to menu design to lease financing to location and size. In addition, after touring several sites, Eloise selected the area and location shed like. She later had discussions with the present owner of what was to become The Yellow Veranda to find out whether she would lease or buy. Taking all the numbers, forms, descriptions and future actions, Eloise produced a strategic plan which explained when and how she would open the business as well as how much money she needed and from which sources.

The proof of the pudding of the first strategic plan is obtaining the resources needed to get started. Money requirements were estimated at about $250,000 for the first year. Eloise applied to the First Federal Bank in her area and to the SBA for loans totaling 75% of the amount.

She brought a three-year financial projection, equipment and inventory requirements, locational expenses and refurbishing costs, salary and utility expenses, projected demand, pricing, marketing tactics, clientele served, hiring and retaining employees, quality controls, and her resumetogether, the strategic plan. The information presented was thorough, substantiated and complete. In addition, she put up her own funds to acquire a lease, to obtain a business license, and retain a lawyer and an accountant. Finally, her strategic plan discussed how she would modify the planning efforts to direct the next steps of operation and eventual growth. She obtained the financing she required, did turn a profit before the first year ended and is today, at 2.5 years into restaurateuring, thinking of opening another country inn.

Company Two: Cleanside, Inc.

Eight years ago, two entrepreneurs had a simple but brilliant idea: contract out the dirty work. Focused on the nursing home sector, this firm provides cost-effective housekeeping, maintenance and repair services for all areas of a facility. The problem, as founder James Foreman saw it, was that janitors and other maintenance people got no respect among staff, were poorly trained since anyone can keep a place clean, and lacked any career incentives in most nursing home situations. His solution was to offer well-trained managers who knew how to motivate their staffs and interface well with facility personnel. All Cleanside employees go through training and are shown the means to career advancement through increasingly responsible management assignments. The performance evaluations are rigorous, but tailored to the growth of each member of the firm. This system has paid off in spades: with over seventy contracts last year, the firm earned a 16% profit. In the last four years, net earnings have doubled each year, and only seven clients have not renewed their contracts in the firms history.

There is a latent demand for such services, which has been increasing rapidly. Capital concerns are insignificant since cash flow starts with the first client payment and a recent public offering netted the company $3.25 million. The only constraint to unabashed growth is management training, availability and performance. When the business volume taxed managements capacity to manage (at any level), James Foreman put a moratorium on obtaining more contracts. This action caused the company to lose new contracts in two instances, but allowed the existing contracts to be handled properly.