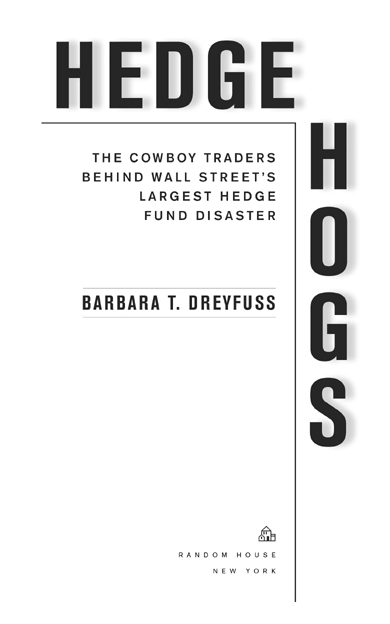

Copyright 2013 by Barbara Dreyfuss

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dreyfuss, Barbara.

Hedge hogs : the cowboy traders behind wall streets largest hedge fund disaster / Barbara T. Dreyfuss.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60501-0

1. Hedge funds. 2. Investment advisors. I. Title.

HG4530.D73 2013 332.64524dc23 2012015889

Jacket design and illustration: Michael Boland

www.atrandom.com

v3.1

To fight, to prove the strongest in the stern war of speculation, to eat up others in order to keep them from eating him, was, after his thirst for splendour and enjoyment, the one great motive for his passion for business. Though he did not heap up treasure, he had another joy, the delight attending on the struggle between vast amounts of money pitted against one anotherfortunes set in battle array, like contending army corps, the clash of conflicting millions, with defeats and victories that intoxicated him.

E MILE Z OLA , Money

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This book was sparked in a roundabout way by my twenty years on Wall Street. It was an accidental career. I started out as a social worker at a foster home program for abandoned and abused children in New York City, then worked in various positions at area hospitals. When I moved to Washington, D.C., my experience in the health care system led to a job at a newsletter company writing about government health policy. Most of my subscribers were executives of hospitals and other health providers.

One day a guy named Mark Melcher rushed into our office to hand-deliver a check for a subscription he insisted must start immediately. He was opening a research office for a large brokerage house, Prudential-Bache Securities, to provide information about Washington to Wall Street clients. He was going to focus on health care and politics. Others would look at tax and budget policy. Wall Street was abuzz with questions about new hospital payment policies and regulations, he explained, and my newsletter provided little-known information about them. He subscribed for a couple of years and we discussed health policy over many lunches. When he learned I was looking for a more challenging job, he offered me a spot as a health policy research analyst.

I didnt really see it as the start of a Wall Street career when I went to work for Prudential-Bache in 1984. After all, I wasnt in New York and the pay was only slightly better than what I was already earning. Rather, I thought Mark a fun person to work with and an experienced, astute analyst who could help me hone my writing and research skills and my understanding of health care policy.

When he hired me, Mark already had over a dozen years experience on Wall Street, writing and speaking about Washington policy on pharmaceutical and other health issues. He was highly regarded by clientsportfolio managers and health care analysts at mutual funds, insurance companies, banks, and money management firms. Like Mark, many had a decade or two of Wall Street experience and were probably closer to fifty than thirty. A few had started their careers working in pharmaceutical or other health care companies or had business school degrees. Although friendly and ready to laugh, they were serious, smart professionals and asked detailed, thoughtful questions.

Wall Street seemed a bit formal back then. Institutional investors, mostly men, dressed in monogrammed white shirts with gold cuff links, fancy suspenders, and suits. Their offices sported conference rooms with lots of mahogany and paintings.

I kept in close phone contact with our firms top clients and traveled around the country to meet them. A large number managed money at mutual funds, firms such as Fidelity and T. Rowe Price, which were exploding as a result of 1980 tax changes allowing employees to put money into 401(k) pretax retirement savings accounts. Others worked at money management firms investing corporate, union, municipal and state pension funds, along with the fortunes of families such as the Rockefellers and Mellons.

These portfolio managers were long-term investors, maintaining the same holdings for weeks, months, years. Each mutual fund and money management company had rules for determining which stocks or bonds to buy or sell, along with parameters for how much to invest in each. Pension plans and wealthy clients also imposed restrictions on money managers. The emphasis was cautious, methodical money management, not speculative, risky activity.

At some firms, committees decided investments and okayed changes in holdings. At others, a portfolio manager had to consult colleagues before buying a hot new stock. The discussion might cause a portfolio manager to reassess his action, or his co-workers might endorse the move and piggyback onto the purchase. Often money managers had firm-wide caps on the number of shares held in one stock. Some firms controlled the number of transactions per manager per quarter. Others regulated the number of stocks, so if a portfolio manager bought a new stock, the firm might need to simultaneously sell something. Some firms limited cash on hand, so when managers sold they also needed to buy. These portfolio managers were known as the buy side of Wall Street, because they bought services from the investment banks and brokerage houses. The banks and brokerage firms handled the actual trading of stocks and bonds and were paid commissions. They also provided research on companies and industries to guide portfolio managers in their investing. This is where I came in. My job was to look beyond the hype of corporate CEOs and public relations professionals and determine what legislation or regulations were in the works that might impact drug companies, hospital firms, and medical device manufacturers.

The federal government was a dominant player in health care through Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Administration. It accounted for a third to half of most hospitals income and paid doctors, labs, and X-ray technicians. Many nursing homes depended on Medicaid revenues. Federal regulators set the rules governing health care providers. The Food and Drug Administration approved all new pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Surprisingly, given the significant impact Washington had on health care, there were only two or three Wall Street analysts in Washington at the time, following developments in Congress and administrative agencies.

The Internet as we know it didnt exist back then. C-SPAN and twenty-four-hour television news broadcasts were in their infancy. There were no telephone hookups to FDA meetings. Only a few investors came to Washington to watch FDA and congressional meetings firsthand. But decisions by the FDA and revelations at Capitol Hill hearings moved stock prices. So my on-the-scene reporting was much in demand.

I attended FDA meetings on specific drugs, arriving early to peruse handouts that often revealed their concerns. Many times I telephoned our worldwide sales force from an FDA meeting to convey breaking news, often negative for a companyan FDA review panel unexpectedly turned down a widely hyped drug for approval, or medical reviewers saw dangers in a new device. Within minutes our salesmen called hundreds of clients and the drug or device companys stock price tanked.