In memory of my beloved father, Howard George Paster, the one true grown-up.

Contents

Foreword

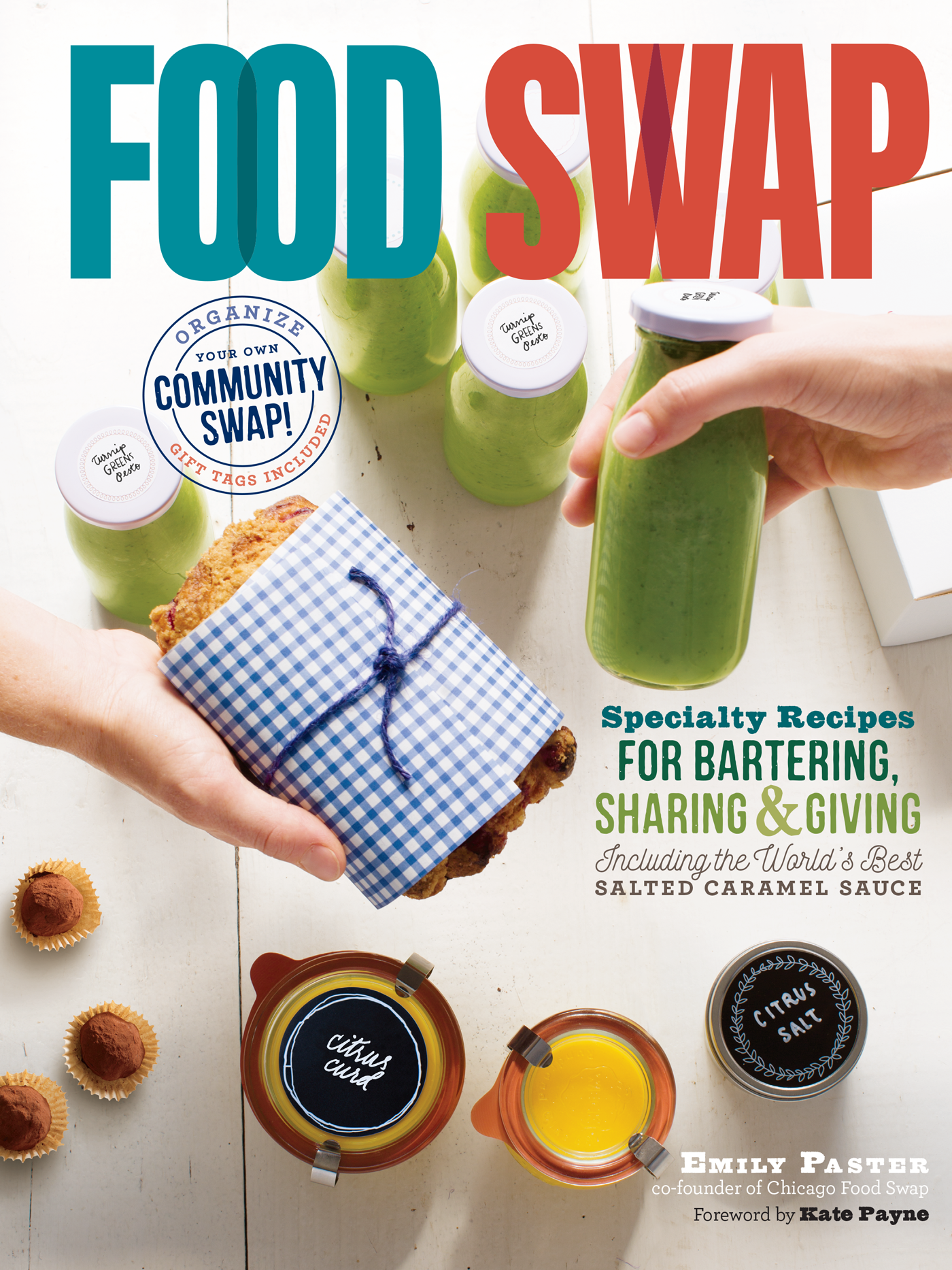

Had you told me about the tidal wave of interest that would burst forth from packing my 900-square-foot apartment in Brooklyn with 26 eager food swappers, I might have laughed. Had you shown me that an event that began with a Twitter exchange then blossomed into plans for a low-key swap party while sipping drinks with Meg at Robertas in Bushwick would become a worldwide movement, Id have laughed again and asked if you wanted to trade me for some marmalade. That very first BK Swappers was rooted in the blossoming DIY food scene of 2010; friends, friends of friends, and even strangers flocked to bring the sharing economy back to food as we knew it. We moved the furniture out of the living room, set up a tea station in the kitchen, popped open the snacks and samples, and had a wonderful time sharing and swapping in the neighborly and communal fashion that I was so hungry for living in a big impersonal city.

Trading food is as old as agriculture, animal husbandry, and communities themselves. Bartering, specialization, and gatherings surrounding food are at the core of human civilization. A modern forum for allowing people to bring what they have and swap items one for one with each other connects us not only with each other, but also with the ingenuity (and necessity) of our ancestors. Modern food swapping allows us to share with each other in the midst of a capitalism-centered economy.

Many of our swappers in Austin, where I returned at the end of 2010, have launched food businesses and now sell their wares, but their roots in the swap run deep. Theres something amazing about not attaching monetary value to everything we do. By valuing the products we create in our home kitchens and acknowledging the inherent value in taking time to make items from scratch, we begin to feel more connected to a larger sharing economy. Those foods are consumed with the knowledge that someone put special care into them, someone you (now) know did work that you did not have to do yourself in order to eat a homemade item.

As I traveled across the country in 2011, touring for my first book, Hip Girls Guide to Homemaking, I was delighted to receive invites from all the new food swaps that were popping up. I attended swaps in Portland; Los Angeles; upstate New York; San Francisco; Minneapolis; Coventry, Connecticut; Bellingham, Washington; and many others. At each swap, though they differed in size, set-up, and city-related mores, the same people were drawn to this grand sharing event. The people who attend food swaps are seeking the community that is supposed to surround food.

Fast forward to now, with many of our founding swaps at or approaching their five-year birthdays, when my good friend and co-creator of Food Swap Network, Emily Han, admits new swaps weekly to the network. Swaps are taking place in the UK, the Netherlands, France, Canada, and of course all over the United States. As you explore these pages, open your mind and your pantry to the community connectivity and deliciousness in store from simply swapping.

Kate Payne

Author of The Hip Girls Guide to Homemaking

Cofounder of the Food Swap Network

Introduction

W hile the idea of trading food is as old as agriculture itself if one neighbor had a cow and the other neighbor had chickens, trading milk for eggs just made good sense how did this ancient form of commerce get revived in the twenty-first century?

Kate Payne and Megan Paska unwittingly launched modern food swapping in 2010, at the intersection of the artisanal, DIY food movement and social media. At the time, Kate, the author of the popular blog and book The Hip Girls Guide to Homemaking, lived in a 600-square-foot Brooklyn apartment and was obsessed with making marmalade. Running out of room for all her jars, Kate mentioned on Twitter that she would be willing to trade some of her stash for other homemade foods. Megan Paska, who blogs at Farmer Megs Digest and has written a book on urban beekeeping, was also living in Brooklyn, where she kept backyard chickens and maintained a rooftop beehive.

Megan responded to Kates Tweet about trading marmalade, which led to an email exchange and then a meeting at a local restaurant where Megan swapped honey and eggs for Kates marmalade. At that meeting, Megan mentioned how much fun it would be to have a larger exchange; they both knew plenty of others just like them in Brooklyn making and producing their own food. And thus the food swap movement was born.

Kate and Megan hosted the first group food swap in March 2010 in Kates small apartment. They set up tables for sampling and swapping, and served snacks and tea. About two dozen people came. Megan came up with the idea for swap sheets, which have been a staple of food swaps ever since, as a way to organize the actual swapping. (For that first swap, Kate and Megan hand-wrote the swap cards as people were arriving.) Everyone had so much fun that Kate and Megan knew it had to become a regular thing. They began hosting food swaps under the guise of BK Swappers every other month.

A Growing Trend

BK Swappers quickly attracted media attention, and when homemade food enthusiasts in other cities learned about the concept of swapping food, they wanted in. Portland, Oregon, was the second city to have its own food swap in late 2010, followed shortly by Minneapolis. (The Minneapolis swap, MPLS Swappers, was shut down by the local health authorities in 2011 after less than one year of operation.) The online television show and blog about food and sustainable living, Cooking Up a Story, created a video about the first event held by the Portland food swap group, PDX Swappers, which brought the concept of food swapping to an even broader audience.

That video inspired Los Angelesbased food writer Emily Han to start the LA Food Swap in spring of 2011. By this time, Kate Payne had moved to Austin, Texas, where she promptly started another food swap, ATX Swappers. That brought the number of official food swaps to five.

In March 2011, an article about BK Swappers appeared in the New York Times. After that, the food swap movement began attracting widespread national attention. Kate, Megan, and Emily were inundated with emails and calls from people wanting to start food swaps in their own cities, something all of the original food swap organizers enthusiastically encouraged. Kate created a private Facebook group for organizers to share tips and best practices. Busy promoting her first book, Kate realized that it would be far more efficient to consolidate all of the food swap organizers knowledge and expertise in one place than it was for her and the others to constantly answer individual queries. Shortly thereafter, in June 2011, Kate and Emily happened to be in Seattle at the same time and got together to discuss the future of food swapping. That meeting became the foundation of the Food Swap Network.