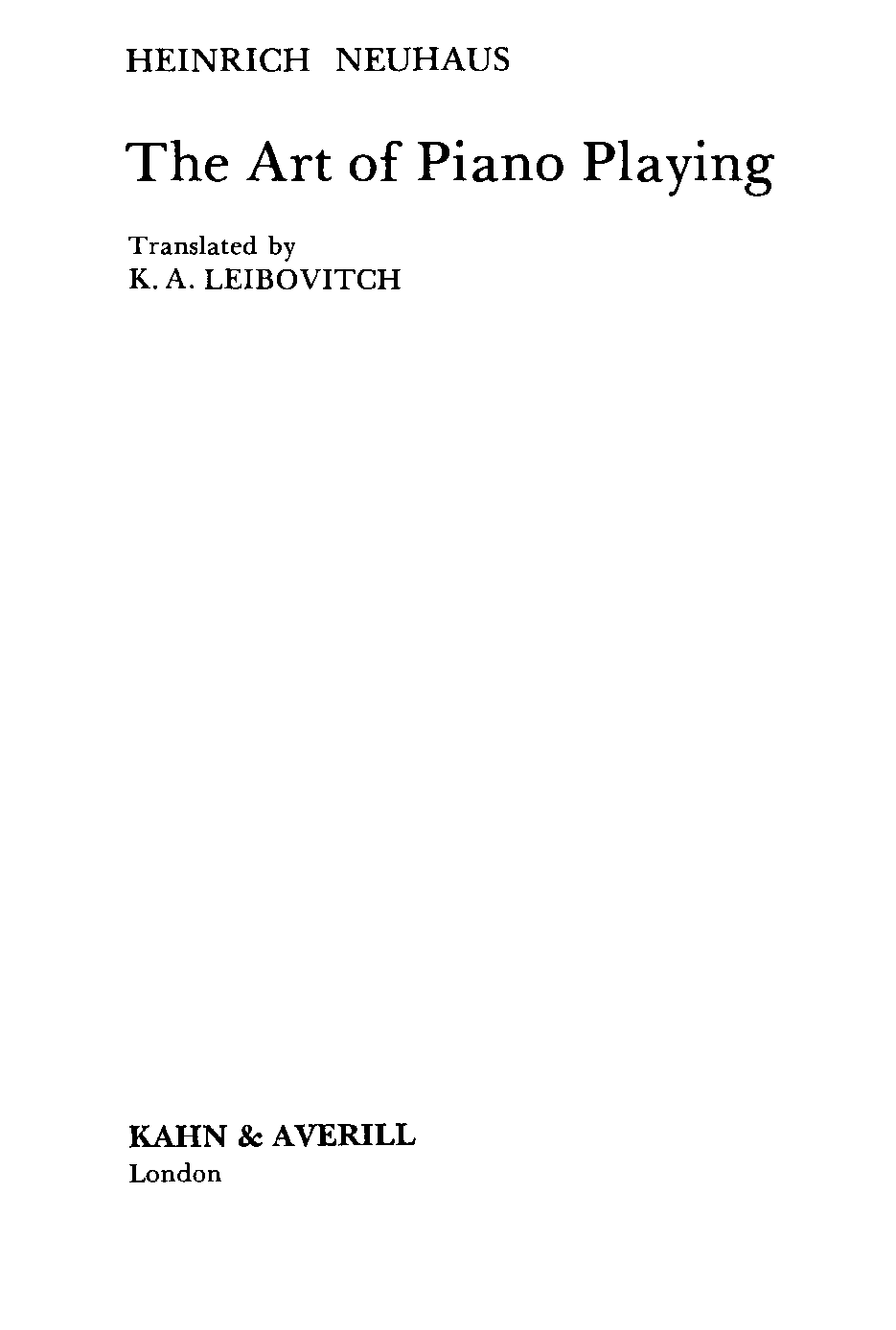

Heinrich Neuhaus - The Art of Piano Playing

Here you can read online Heinrich Neuhaus - The Art of Piano Playing full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Kahn & Averill, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Art of Piano Playing

- Author:

- Publisher:Kahn & Averill

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Art of Piano Playing: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Art of Piano Playing" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Neuhaus taught at the Moscow Conservatory and his pupils included some of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century: Emil Gilels, Sviatoslav Richter, Nina Svetlanova, Alexei Lubimov and Radu Lupu. His legacy continues today and many teachers around the world regard this book as the most authoritative on the subject of piano playing.

**

The Art of Piano Playing — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Art of Piano Playing" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Art of Piano Playing

This edition published in 1993 by Kahn & Averill

9 Harrington Road, London SW7 3ES

First published in Great Britain in 1973 by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd

English translation copyright by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd

Music examples numbers: 1-50, 52, 53, 82-85, 89-95, 97-100 reproduced by kind permission of Musikverlag Hans Gerig, Cologne

All rights reserved

Reprinted 1997, 2001, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2010

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1 871082 45 5

ISBN 9781 871082 45 6 (from Jan 2007)

Printed in Great Britain by Halstan & Co Ltd., Amersham, Bucks

This book is dedicated to

my dear colleagues, the teachers and the pupils who are studying the art of piano playing"

Heinrich Neuhaus was born in 1888 in Elizavetgrad (now Kirovograd) into a family of musicians. Both his father and mother were piano teachers. The father, Gustav Neuhaus, born in 1847 in the Rhineland, had studied under Ferdinand Hiller who, in turn, as a young man had known Beethoven. His mother, Olga Blumenfeld, was the sister of Felix Blumenfeld, a distinguished pianist, conductor and teacher, first in Petersburg, and then in Moscow; Horowitz was one of his most famous pupils. Through his maternal grandmother he was related to Karol Szymanowski who became a lifelong friend.

Since his parents could rarely spare the time to teach their son, Heinrich Neuhaus was, strictly speaking, self-taught, playing the piano and improvising passionately since early childhood. The main formative influence on his musical development came from Felix Blumenfeld, on his rare visits to his sisters home.

Heinrich Neuhaus made his first public appearance at the age of eleven, playing some Chopin Waltzes and an Impromptu. In 1902 he accompanied Misha Elman in a recital in Elizavetgrad. His first solo recital took place in Germany in 1904 and from then he gave several concerts in Germany and Italy while studying under Godowsky, first in Berlin and then in Vienna, from where he returned to Russia at the outbreak of the First World War.

In 1922 he began teaching at the Moscow Conservatoire and helped to create in 1932 the famous Moscow Central Music School for specially gifted children. From 1934 to 1937 he was Director of the Moscow Conservatoire, a post he relinquished so as to be able to devote himself entirely to teaching, for the sake of which he had already sacrificed most of his career as a concert pianist.

Amongst his pupils were Radu Lupu, Emil Gilels and Sviatoslav Richter who called him an artist of unique genius, a great teacher and friend. Seldom have artistic gifts been so closely matched by the qualities of selfless devotion, deep humanity, true culture and a great capacity for bestowing and winning friendship. He died on 1oth October 1964. This book bears witness to his achievements as man, musician and teacher.

THE EDITOR

I wrote my book a little at a time, in between my work (my work being teaching and concert playing) and before sending it off to the publisher I condensed what I had written so thoroughly that not more than half my original manuscript reached the printer. But now I do not feel the energy to rewrite or add to my book; let it come out in the unpolished state in which it first appeared.

At the beginning I did not give much thought to the publication of my notes. It was rather an unconstrained conversation with acquaintances and pupils; hence the discrepancy between the style of my book and what is usually expected from a work on methodology. But then I am not a theoretician and never shall be.

Several persons considered that I should not have made such frequent use of foreign words and expressions. They are probably right. All of this could have been said in Russian. The fault lies in the conversational style of these pages, for I have since my childhood known several languages and been accustomed to use certain expressions in one particular language; and in writing this book I put down my thoughts just as they came to me.

On page 124 I have definitely made a misstatement (beginning with the words A few words more about octaves). Heremay I be forgiven! I simply prevaricated and I confess it freely. I prevaricated in the sense in which one poet uses the word, taking it to mean not an untruth, but rather a superfluous addition to truth. I can only explain this regrettable incident by the fact that I suffered so much from sympathetic fingers (the middle fingers which catch on the keys between the thumb and fifth finger when playing an octave) that I exaggerated the meaning of the hoop and in spite of my own practice, I misrepresented the position of the wrist which should be slightly raised. This is how all pianists play, including myself. My prevarication was due to a desire to avoid the cacophony caused by the middle fingers, but I overdid it and the result was a false statement. I beg the reader to take this correction into account.

One of the faults of my book is the insufficient number of examples and of the considerations and advice that they would have called forth. This is particularly true of the chapters on rhythm, tone, and even technique. I could have given hundreds of examples that could have been useful to learners. But the reader has doubtless noticed that I tried rather to prompt him to think further and independently and felt that this small book should and could only guide the readers thinking.

Another fault of my book is that I have not indicated by a single word my attitude towards modern music, with the exception of some cursory references to Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Szymanowski and a few others. In our rapidly changing times it is very difficult to come to any final conclusionseven for oneselfthat do not claim to be of general significance. My own perception of certain phenomena and my opinions of them are often contradictory. For instance, the phenomenon of dodecaphony and serial music often seems to me to resemble in its basic principles a complicated and interesting game of patience. For some moments this music can give me a certain particular kind of pleasure, but only for a few moments (for instance in Webern). Thinking of the weaker adepts of this trend I cannot help feeling that for them this is a means of inventing music (or rather something similar to music) although they have no talent nor even a musical ear. Thanks to generous patrons, propaganda and advertisements, they achieve a certain standing in the world which they would not have achieved otherwise. But the question of dodecaphony is closely related to many general problems of twentieth-century music; it is very complicated and to be quite honest still not quite clear to me.

Now a few more words about the way this book was written.

I wrote it for about three weeks a year! Usually when I was on holiday. In winter when I was submerged by my teaching work and in addition gave recitals which I had to prepare, I had neither the time nor the inclination to put down on paper my views on the art of the piano, particularly since I spoke about it in some form or other all day and every day in class. Now the situation has changed. The trouble with my hand, the result of acute polyneuritis, is becoming increasingly serious and it is now two years since I have had to stop playing altogether. Even at home, for myself, I no longer play; I am too distressed by my helpless hand and after all one can read music with ones eyes, or listen to the radio or to records. To be quite honest I think that even teaching is now inadvisable for me and I am thinking of retiring very soon. To work with pianists only as a conductor, unable to demonstrate my intention and advice by showing what I mean on the piano, as I used to before, is really too upsetting and can satisfy neither me, nor (probably) my pupils. But having said good-bye to the piano (but not, of course, to music) and partly also to teaching, I do not feel very inclined to write about it. In my book I tried most of all (as in all my teaching work) to awaken a love of music. I do not know how far I have succeeded, but still I decided not to add anything substantial to my book and to allow the second edition to appear in the same unpolished state as the original, merely correcting a few mistakes. So much has been written on this subject that one book more or less does not really matter.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Art of Piano Playing»

Look at similar books to The Art of Piano Playing. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Art of Piano Playing and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.