Peter Wadhams

A FAREWELL TO ICE

with a Foreword by Walter Munk

Contents

In memory of old Arctic friends

Bill Campbell

Max Coon

Norman Davis

Moira and Max Dunbar

Geoff Hattersley-Smith

Wally Herbert

Lyn Lewis

Ray Lowry

Nobuo Ono

Erkki Palosuo

Gordon Robin

Unsteinn Stefnsson

Charles Swithinbank

Norbert Untersteiner

Thomas Viehoff

List of Plates

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be happy to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

List of Figures

1.1

2.1

2.2

2.3

3.1

4.1

4.2

4.3

5.1

5.3

5.4

5.5

6.1

6.2

7.1

7.2.

7.3

8.1

8.2

8.3

8.4

9.1

11.1

12.1

12.2

12.3

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be happy to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

Foreword

Peter Wadhams has been a polar researcher for forty-seven years, during which time he has observed and measured major changes in the nature of sea ice cover in the polar regions. In this book, he first gives a brief review of the planet and the development of its ice on land and sea. He goes on to describe the profound transformations that he has witnessed during his career. The area of Arctic sea ice in summer has dwindled from more than 8 million square kilometres to less than half that, leading to projections for the imminent occurrence of ice-free summers.

The melting of sea ice is not just a curious phenomenon in a remote part of our world: it sharply decreases the amount of solar radiation reflected back into space, from 60 per cent to 10, further accelerating the planetary warming cycle. Frozen sediments, which have lain undisturbed since the last Ice Age, are now releasing plumes of methane a very potent greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. A Farewell to Ice is both an authoritative report on the state of the Arctic today and a timely reminder of the global threat posed by the loss of its sea ice.

Walter Munk

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California

1

Introduction: A Blue Arctic

I have been a polar researcher since 1970. For most of those years I had the privilege of being based at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, and served as its Director. Established as a memorial to Captain Robert Falcon Scott, it was a haven and meeting place for polar researchers of every kind of discipline, many of whom took long leaves of absence from their host institutions to study in its incomparable library. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s I was in the polar regions (usually the Arctic) every year, sometimes several times, and, like my colleagues in Europe, America, Russia and Japan, devoted myself to understanding the basic physical processes which occur in sea ice and which determine how it grows, decays and moves. Field research into ice is very difficult, and at times dangerous, and few of us considered that the object of our efforts, the Arctic Ocean, could be changing before our eyes. It was hard enough trying to understand how the Arctic worked in the first place. Yet changing it was. I was fortunate enough to be one of the first to obtain definite evidence of this, when I compared surveys of ice thickness that I had made from submarines in 1976 and 1987 and found a 15 per cent loss of average thickness. This result, published in Nature in 1990, Something truly dramatic was going on. Polar researchers raised their eyes from their own specialized studies and started to consider the larger picture. They have become climate change specialists, indeed climate change pioneers, since it is in the Arctic that global change appears to be most rapid and drastic.

), and eventually, when we were in the middle of the Northwest Passage, we had to be rescued by a heavy Government icebreaker, the John A. Macdonald. In those days, a battle with sea ice in the Canadian Arctic was considered normal. In 19036 it took Amundsen three years to navigate the Northwest Passage, and the second ship to make the Passage, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police schooner St. Roch, needed two seasons in 19424.

Today a ship entering the Arctic from Bering Strait in summer finds an ocean of open water in front of her. This blue water extends far to the north, stopping not far short of the North Pole. By the time this book is published it is possible and, according to many predictions, likely that the Pole itself will be uncovered for the first time in tens of thousands of years. The Northwest Passage is now easily navigable, and by the end of 2015 a total of 238 ships had sailed through it. In September 2012 sea ice covered only 3.4 million square kilometres (km2) of the Arctic Oceans surface, down from 8 million km2 in the 1970s. It is difficult to overstate what this means in terms of planetary change. Our planet has actually changed colour. We all remember the first beautiful photograph of planet Earth rising from behind the Moon, taken by the Apollo-8 astronauts, a delicate blue sphere, isolated in the cosmos, which contains all that we know of life. That sphere was white at both ends. Today, from space, the top of the world in the northern summer looks blue instead of white. We have created an ocean where there was once an ice sheet. It is Mans first major achievement in reshaping the face of his planet, and it is of course an unintended achievement, with dubious and possibly catastrophic consequences to follow.

Things are actually even worse than appearances would suggest. My sonar measurements showed that the average ice thickness dropped 43 per cent between 1976 and 1999., it will leave us with an ice-free September in the Arctic, and within a few years after that the ice-free season will expand to four or five months.

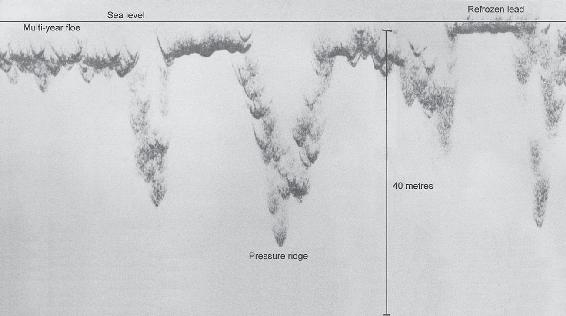

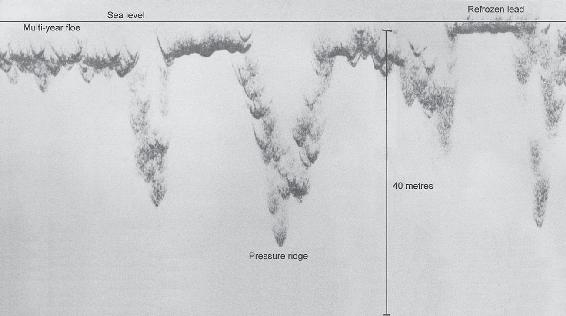

Figure 1.1: Pressure ridges in multi-year ice, recorded by upward-looking sonar from a submarine. The largest is 30 metres deep.

The consequences of a collapse of Arctic summer ice will be dramatic. Two huge effects will be unleashed. First, once summer ice yields to open water, the albedo the fraction of incoming solar radiation which is reflected straight back into space drops from 0.6 to 0.1, which will further accelerate warming of the Arctic and of the whole planet. The albedo change from the loss of the last 4 million km2 of ice will have the same warming effect on the Earth as the last twenty-five years of carbon dioxide emissions. Secondly, removal of the ice cover will take away a vital air-conditioning system for the Arctic. So long as some ice is present in summer, however thin, the sea surface temperature cannot rise above 0C, since any warmer water loses its heat in melting some of the overlying ice. When the overlying ice is gone, the surface water can warm up by several degrees in summer (satellite observations have shown 7C), and over the shallow continental shelves wind-induced mixing extends this heat down to the seabed. This then thaws the surface layer of the offshore permafrost, frozen seabed sediments which have lain there undisturbed since the last Ice Age. The thawing offshore permafrost will trigger the release of huge plumes of methane from the disintegration of methane hydrates trapped in the sediment. Methane has a greenhouse warming effect twenty-three times greater per molecule than carbon dioxide. An annual RussianUS expedition to the East Siberian Sea has already observed methane plumes welling up from the seabed, while other expeditions have seen methane plumes in the Laptev and Kara seas. If this release causes general atmospheric levels of the gas to rise, it will give a further immediate boost to global warming. I have written this book to explain these dramatic changes, and how and why the loss of Arctic ice is a threat to us all, not just an interesting change happening in a remote part of the world.