Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

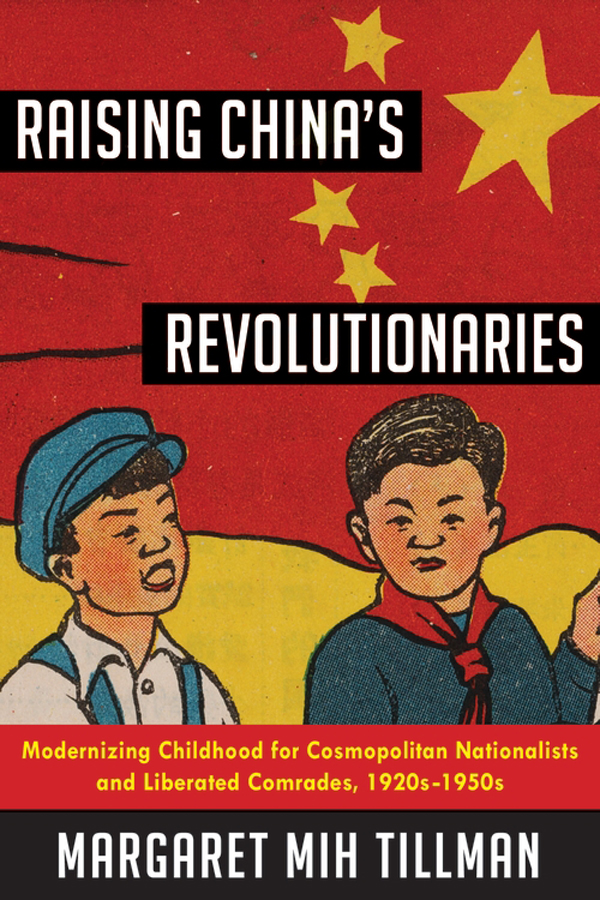

RAISING CHINAS REVOLUTIONARIES

Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

STUDIES OF THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia.

Raising Chinas Revolutionaries

MODERNIZING CHILDHOOD FOR COSMOPOLITAN NATIONALISTS AND LIBERATED COMRADES, 1920S1950S

Margaret Mih Tillman

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54622-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tillman, Margaret Mih, author.

Title: Raising Chinas revolutionaries : modernizing childhood for cosmopolitan nationalists and liberated comrades, 1920s1950s / Margaret Mih Tillman.

Description: New York, NY : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004616 (print) | LCCN 2018029545 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231185585 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Child rearingChinaHistory. | Child welfareChinaHistory. | ChildrenChinaHistory. | FamiliesChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC HQ792.C5 (ebook) | LCC HQ792.C5 T56 2018 (print) | DDC 362.70951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004616

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

Cover image: Cover of New Children , Cotsen Childrens Collection, Princeton University Library

For my parents, Hoyt Cleveland Tillman and Cristina Mih Tillman

The great person is one who does not lose his childlike heart.

Mencius

Is not the character of every epoch revived, perfectly true to nature, in the childs nature? Why should the childhood of human society, where it had obtained its most beautiful development, not exert an external charm as an age that will never return? There are ill-bred children and precocious children.

Karl Marx, Grundrisse

Contents

I n the 1970s and 1980s Communist China opened its doors to the United States. Upon reentering China for the first time in decades, Americans marveled at the distinctiveness of ordinary life in the Peoples Republic (PRC). For example, educational psychologists enthusiastically reported that preschool children demonstrated Communist visions of justice.

At this time, my family was among the first to benefit from cross-cultural exchange in the normalization of relations between the United States and China. My father, a China historian, had received grants from both the Fulbright Foundation and the American Academy of Sciences Committee for Scholarly Communication with the PRC. With these grants, we spent two years in Beijing. My older brother attended the elementary school, and I attended the preschool, attached to Peking University in the early 1980s.

Preschool regulations governed my small world, and I brought those rules home. For example, as a preschooler walking on the streets of Beijing, I ordered my family to march in a line according to heightit simply followed that, as the smallest, I was of course also first . There we were: a toddler at the helm, leading a green-eyed boy, a Chinese American woman, and a blue-eyed American man. Passing us, a bicyclist once flipped over his bike, laughing uncontrollably. No doubt we were a strange sight.

When U.S. experts toured Chinese classrooms, they often watched kindergartners perform plays about fairness, sharing, and justice. I absorbed these lessons and took them with me to Taiwan when we visited my grandmother. Years after Mao Zedong died, I echoed the lines, Ill tell Chairman Mao on you!I was threatening to report a bully. Of course, those words assumed special meaning because that little reactionary was on a Taiwanese playground. My grandmother, amused, repeated the story.

Such stories inevitably raise questions while both challenging and reinforcing assumptions. When children speak politically, we can reflect on our assumptions that children are innocent and ignorant of the world. It also becomes more obvious, in those situations, that we need to examine more closely our preconceptions about authentic political action as slogans are repeated, mimicked, and performed.

Similar stories are preserved in archives. In the Beijing Municipal Archives, I opened a set of files, written by kindergarten staff and administrators in the early 1950s, reporting on the behavior of children. They recounted children surpassing teachers at classroom management by exerting peer pressure. If one child began to wander away from the marching line, for example, the remainder would quip, Little ducky fell out of line! And the errant child would return. Similarly, kindergartners sometimes sat in a circle to criticize and reform the behavior of misbehaving classmates. Taking charge of the curriculum through committee work, the children in these reports infused science lessons with political slogans, which they drafted and revised collectively. Then they returned home to instruct their parents. Unencumbered by the influences of feudal Old China, kindergartners led the vanguard of communism.

To what degree can a historian trust such stories to represent the authentic voices of children? After all, teachersespecially holdovers from previous regimeshave been known to obfuscate their resistance to top-down policy directives such as in Nazi and Communist Germany, as well as in the United States. And yet my own personal experiencesand those of othersencouraged me to believe that such stories were also not purely fictional.

In the course of my research, I have enjoyed discussions with multiple generations of Chinese people who have shared with me their stories about kindergarten. Some of these stories were very similar to mine and were also told in a bemused way by adults enchanted with the incongruence of childhood innocence and adult politics. Other people felt hurt by what they now consider the imprint of political manipulation. This range reflects a diversity of experiences among people who learned to embrace particular social identities in the political life of China over the course of its history.

Especially given my own place of privilege as an American guest in Chinese society, I do not attempt to reconstruct the subjectivities of Chinese individuals. This book is about the discursive construction of modern childhood and the institutional mechanisms used to construct it; it is not a social history of demographical changes among Chinese children, nor is it an anthropological study of childrens perspectives. Because this book examines the efforts of adults on behalf of children, my methodology sometimes results in privileging top-down perspectives over the voices of children themselves.

This study offers instead historical context for the early childhood education in socialist China that might have eluded U.S. experts who visited China in the 1980s. U.S. experts, of course, approached their task through the lens of established disciplines and professions. And I had, over the years, invested meaning in my early experiences in a rather desultory and disconnected way. Research for this book has transformed my recollections into historicized appreciation of the particularity of those distinct moments when I happened to be a child in the system. Family conversations meanwhile have oriented my research into a vast and open-ended subject that could have gone in many directions.