Jacket copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Running Press, a division of Hachette Book Group. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

T his is a book about math. That was the plan, anyway.

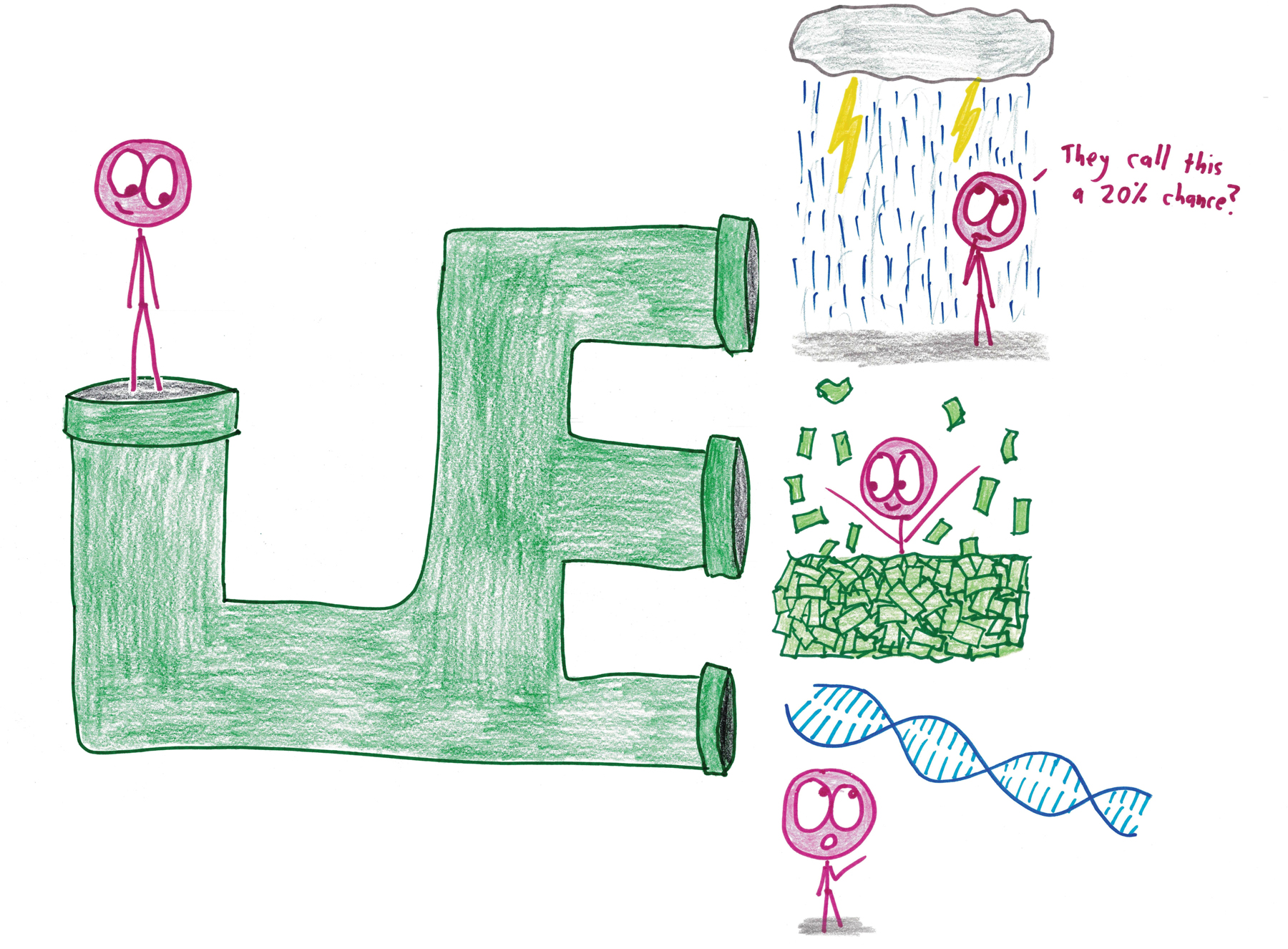

Somewhere, it took an unexpected left turn. Before long, I found myself without cell phone reception, navigating a series of underground tunnels. When I emerged into the light, the book was still about math, but it was about lots of other things, too: Why people buy lottery tickets. How a childrens book author swung a Swedish election. What defines a Gothic novel. Whether building a giant spherical space station was really the wisest move for Darth Vader and the Empire.

Thats math for you. It connects far-flung corners of life, like a secret system of Mario tubes.

If this description rings false to you, its perhaps because youve been to a place called school. If so, you have my condolences.

When I graduated from college in 2009, I thought I knew why mathematics was unpopular: It was, on the whole, badly taught. Math class took a beautiful, imaginative, logical art, shredded it into a bowl of confetti, and assigned students the impossible, mind-numbing task of piecing the original back together. No wonder they groaned. No wonder they failed. No wonder adults look back on their math experiences with a shudder and a gag reflex. The solution struck me as obvious: Math required better explanations, better explainers.

Then I became a teacher. Undertrained and oozing hubris, I needed a brutal first year in the classroom to teach me that, whatever I knew about math, I didnt yet understand math education, or what the subject meant to my students.

One day that September, I found myself leading an awkward impromptu discussion of why we study geometry. Did grown-ups write two-column proofs? Did engineers work in no calculator environments? Did personal finance demand heavy use of the rhombus? None of the standard justifications rang true. In the end, my 9th graders settled on We study math to prove to colleges and employers that we are smart and hardworking. In this formulation, the math itself didnt matter. Doing math was a weightlifting stunt, a pointless show of intellectual strength, a protracted exercise in rsum building. This depressed me, but it satisfied them, which depressed me even more.

The students werent wrong. Education has a competitive zero-sum aspect, in which math functions as a sorting mechanism. What they were missingwhat I was failing to show themwas maths deeper function.

Why does mathematics underlie everything in life? How does it manage to link disconnected realmscoins and genes, dice and stocks, books and baseball? The reason is that mathematics is a system of thinking, and every problem in the world benefits from thinking.

Since 2013, Ive been writing about math and educationsometimes for publications like Slate, the Atlantic, and the Los Angeles Times, but mostly for my own blog, Math with Bad Drawings. People still ask me why I do the bad drawings. I find this odd. No one ever wonders why I choose to cook mediocre food, as if Ive got a killer chicken lorange that, on principle, I decline to serve. Its the same with my art. Math with Bad Drawings is a less pathetic title than Math with the Best Drawings I Can Manage; Honestly, Guys, Im Trying, but in my case they are equivalent.

I suppose my path began one day when I drew a dog on the board to illustrate a problem, and got the biggest laugh of my career. The students found my ineptitude shocking, hilarious, and, in the end, kind of charming. Math too often feels like a high-stakes competition; to see the alleged expert reveal himself as the worst in the room at somethinganythingthat can humanize him and, perhaps, by extension, the subject. My own humiliation has since become a key element in my pedagogy; you wont find that in any teacher training program, but, hey, it works.

Lots of days in the classroom, I strike out. Math feels to my students like a musty basement where meaningless symbols shuffle back and forth. The kids shrug, learn the choreography, and dance the tuneless dance.

But on livelier days, they see distant points of light and realize that the basement is a secret tunnel, linking everything they know to just about everything else. The students grapple and innovate, drawing connections, taking leaps, building that elusive virtue called understanding.

Unlike in the classroom, this book will sidestep the technical details.Youll find few equations on these pages, and the spookiest ones are decorative anyway. (The hard core can seek elaboration in the endnotes.) Instead, I want to focus on what I see as the true heart of mathematics: the concepts. Each section of this book will tour a variety of landscapes, all sharing the underground network of a single big idea: How the rules of geometry constrain our design choices. How the methods of probability tap the liquor of eternity. How tiny increments yield quantum jumps. How statistics make legible the mad sprawl of reality.

Writing this book has brought me to places I didnt expect. I hope that reading it does the same for you.

BEN ORLIN, October 2017

T o be honest, mathematicians dont do much. They drink coffee, frown at chalkboards. Drink tea, frown at students exams. Drink beer, frown at proofs they wrote last year and cant for the life of them understand anymore.