Jacket copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

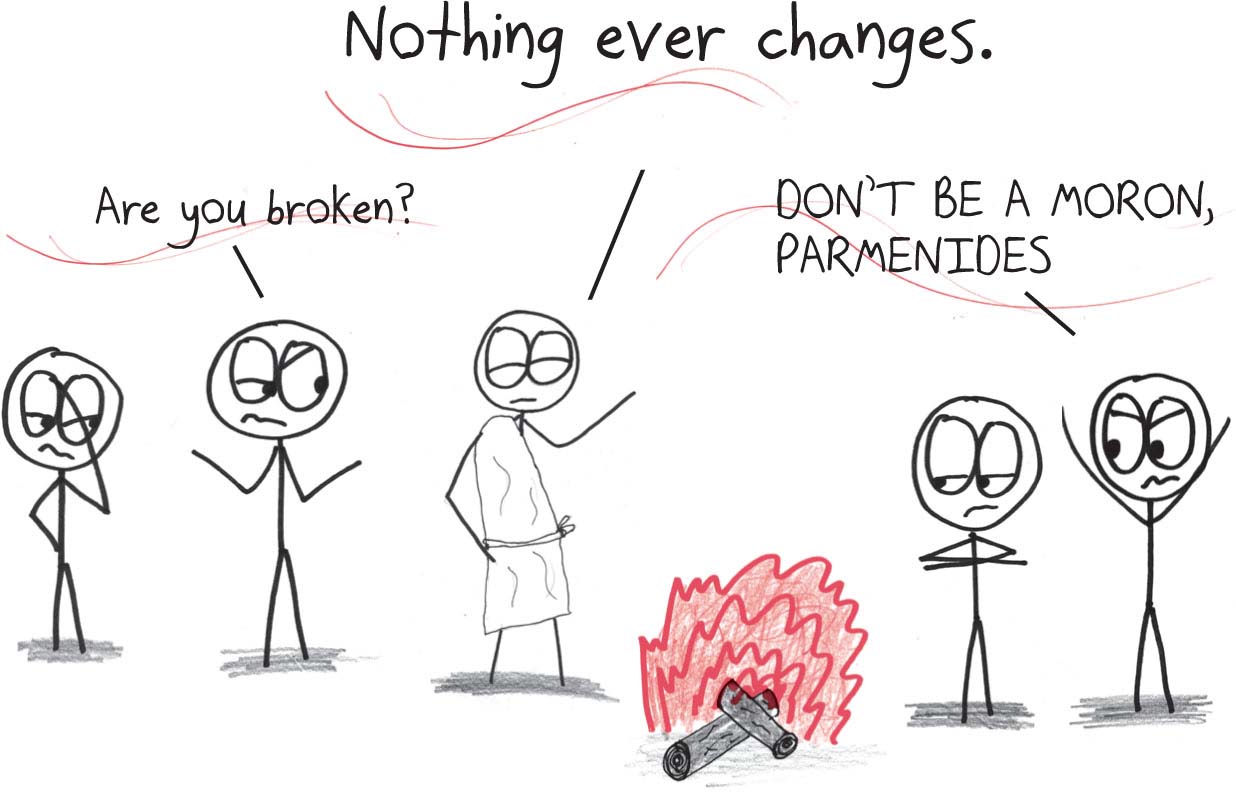

What is, said the philosopher Parmenides, not quite a million days ago, is uncreated and indestructible, alone, complete, immovable and without end. Its a bold philosophy. Parmenides permitted no divisions, no distinctions, no future, no past. Nor was it ever, nor will it be, he explained; for now it is, all at once, a continuous one. To Parmenides, the universe was like Los Angeles traffic: eternal, singular, and unchanging.

A million days later, it remains a very stupid idea.

Cmon, Parmenides. You can lull us with poetry and ply us with adjectives, but were not dupes. A million days ago, there were no Buddhists, Christians, or Muslims, because Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad had yet to be born. A million days ago, Italians did not eat tomato sauce, because Italy wasnt a concept and the closest tomatoes grew 6000 miles away. A million days ago, 50 or 100 million humans walked the Earth; now, that many people visit Disney-branded theme parks each year.

In fact, Parmenides, only two things were the same a million days ago as today: (1) the ubiquity of change, and (2) your philosophys profound and irredeemable wrongness.

Thats the last well hear of Parmenides in this book (although his savvier disciple Zeno will pop up later). Good riddance to toga-clad stoners, I say. For now, we jump ahead, past his wiser contemporary Heraclitus (you cant step in the same river twice), to arrive in the late 17th century, a mere 120,000 or 130,000 days ago. Thats when a scientist named Isaac Newton and a polymath named Gottfried Leibniz birthed this books protagonist. It was a fresh form of mathematics, a language of change, a stab at quantifying the flux and flow of this wobbling top called Earth.

Today, we call that math calculus.

The first tool of calculus is the derivative. Its an instantaneous rate of change, telling us how something is evolving at a specific moment in time. Take, for example, the apples velocity precisely as it strikes Newtons noggin. A second earlier, the fruit was moving a smidge slower; a second later, it will be moving in a different direction entirely, as will the history of physical science. But the derivative does not care about the second before, or the second after. It speaks only to thismoment, to an infinitesimal sliver of time.

Calculuss second tool is the integral. It is the sum of infinite pieces, each infinitesimally small. Picture how a series of circles, each shadow-thin, can unify to create a solid object: a sphere. Or how a group of humans, each as tiny and negligible as an atom, can together constitute a whole civilization. Or how a series of moments, each of them zero seconds in itself, can amount to an hour, an eon, an eternity.

Each integral speaks to a totality, to something galactic, which the panoramic lens of our mathematics can somehow capture.

The derivative and integral have earned a lofty reputation as specialized technical tools. But I believe they can offer more. You and I are like little boats, knocked by waves, spun by whirlpools, thrown by rapids. The derivative and the integral, I hold, are pocket-sized philosophies: extendable oars for navigating this flood-swollen river of a world.

Hence, this book, and its attempts to distill wisdom from mathematics.

In the first half, Moments, well explore tales of the derivative. Each extracts an instant from the babbling stream of time. Well consider a millimeter of the moons orbit, a nibble of buttered toast, a dust particles erratic leap, and a dogs split-second decision. If the derivative is a microscope, then each of these stories is a carefully chosen slide, a scene in miniature.

In the second half, Eternities, well call upon the integral and its power to unify infinite droplets into a single stream. Well encounter a circle fashioned from tiny slivers, an army raised from myriad soldiers, a skyline built of anonymous buildings, and a cosmos heavy with a billion trillion stars. If the integral is a widescreen cinema, then each of these stories is a sweeping epic that youve got to see in theaters. The TV at home wont do it justice.

I want to be clear: the object in your hands wont teach you calculus. Its not an orderly textbook, but an eclectic and humbly illustrated volume of folklore, written in nontechnical language for a casual reader. That reader may be a total stranger to calculus, or an intimate friend; Im hopeful that the stories will bring a little mirth and insight either way.

![Chris Monahan [Chris Monahan] - Calculus II](/uploads/posts/book/119088/thumbs/chris-monahan-chris-monahan-calculus-ii.jpg)